The “Loud but Hot” Paradox in Small Cabins

We see this support ticket frequently during the summer months: A site manager installs a rugged Portable DC Air Conditioner in a 4×6 security guard booth. The unit turns on, the fan roars to life, and the display shows active cooling mode. Yet, three hours later, the temperature inside the booth hasn’t dropped below 28°C (82°F), and the guard is drenching in sweat.

The immediate assumption is a refrigerant leak or a compressor failure. However, in 90% of these cases, the unit is mechanically perfect. The problem is purely aerodynamic.

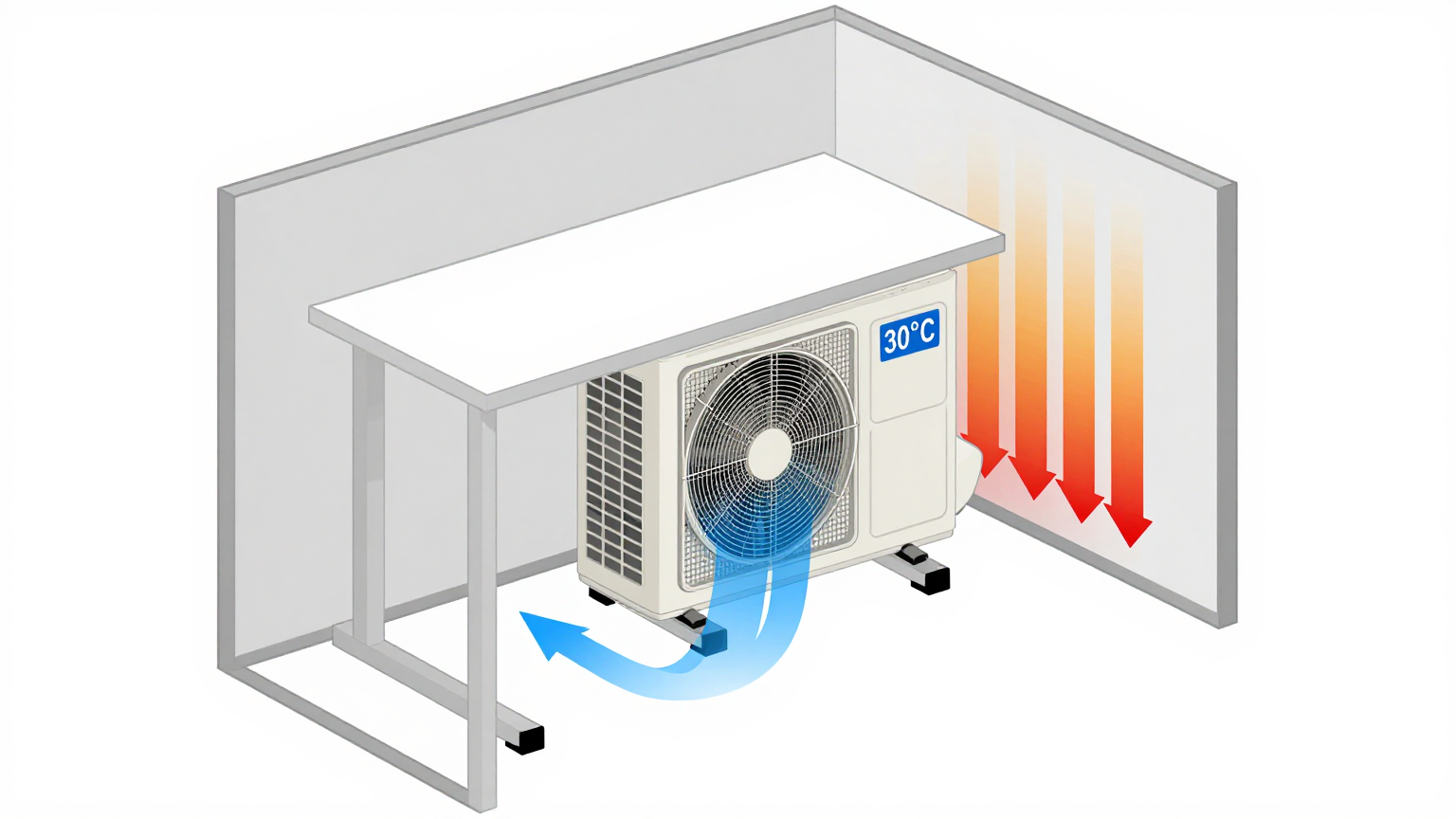

In the tight confines of a remote cabin or sentry box, users often shove the portable unit into a corner or under a desk to save precious legroom. Without realizing it, they have created a massive portable DC AC airflow blockage. The unit is suffocating, fighting against its own intake restriction, and essentially churning the same hot air over and over again.

Target Airflow: ~250-300 CFM (typical for 2-3kW cooling)

Minimum Clearance: 150mm (6 inches) on all intake faces

Static Pressure Limit: Varies by fan curve, typically <50 Pa for portable units

1. The Physics of Air Starvation

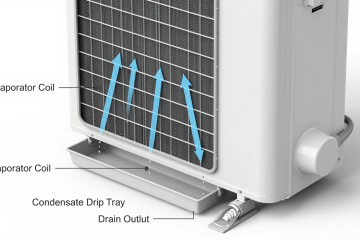

To understand why placement matters, we must look at how a portable AC rejects heat. Unlike a split system where the noisy, hot condenser is outside, a portable unit houses everything in one chassis. It relies on a powerful centrifugal fan to pull ambient air across the condenser coil to carry away heat.

When you push the unit against a wall or tuck it tightly into a cabinet, you drastically increase the intake static pressure. The fan has to work twice as hard to pull air through a 2cm gap instead of a 20cm gap.

The Fan Curve Collapse

Every fan has a performance curve: as resistance (static pressure) goes up, airflow (CFM) goes down. When the intake is blocked by a wall, the airflow across the condenser coil drops below the critical design threshold. The refrigerant cannot condense fully, head pressure spikes, and the cooling capacity plummets—even though the compressor is running at full amps.

2. Short-Cycling: The Invisible Loop

Airflow blockage doesn’t just mean “no air.” A more insidious form is Hot Air Recirculation (Short-Cycling). This happens when the discharge air (cool) or the exhaust air (hot) is deflected back into the unit’s intake due to obstructions.

In a small guard booth, placing the unit under a desk is a classic mistake. The hot exhaust hose might be routed correctly, but the cool air outlet hits the underside of the desk and bounces back down to the floor—right where the return air intake is located.

The Consequence: The AC sucks in its own 15°C discharge air, thinks the room is freezing, and cycles the compressor off. Meanwhile, the guard’s head level is still 30°C. This “false satisfaction” cycle wears out the compressor relay and fails to cool the actual occupied zone.

3. The “Half-Blocked” Hose Scenario

Another common source of portable DC AC airflow blockage is the exhaust ducting itself. In temporary structures like construction site offices, users often route the flexible exhaust hose through a partially open window or a makeshift hole in the wall.

If the hose is kinked, crushed, or extended beyond its rated length (typically 1.5 – 2 meters), the backpressure becomes too high. We have seen installations where a 5-inch diameter hose is squeezed through a 3-inch window gap. This 40% reduction in cross-sectional area acts like a throttle valve on your heat rejection system.

- Symptom: The exhaust hose feels dangerously hot to the touch.

- Result: The thermal overload switch trips after 20 minutes of operation.

4. Solving the Space vs. Cooling Conflict

We understand that floor space in a 2×2 meter booth is non-negotiable. However, physics is also non-negotiable. Here is how to integrate a portable DC unit without sacrificing space or performance:

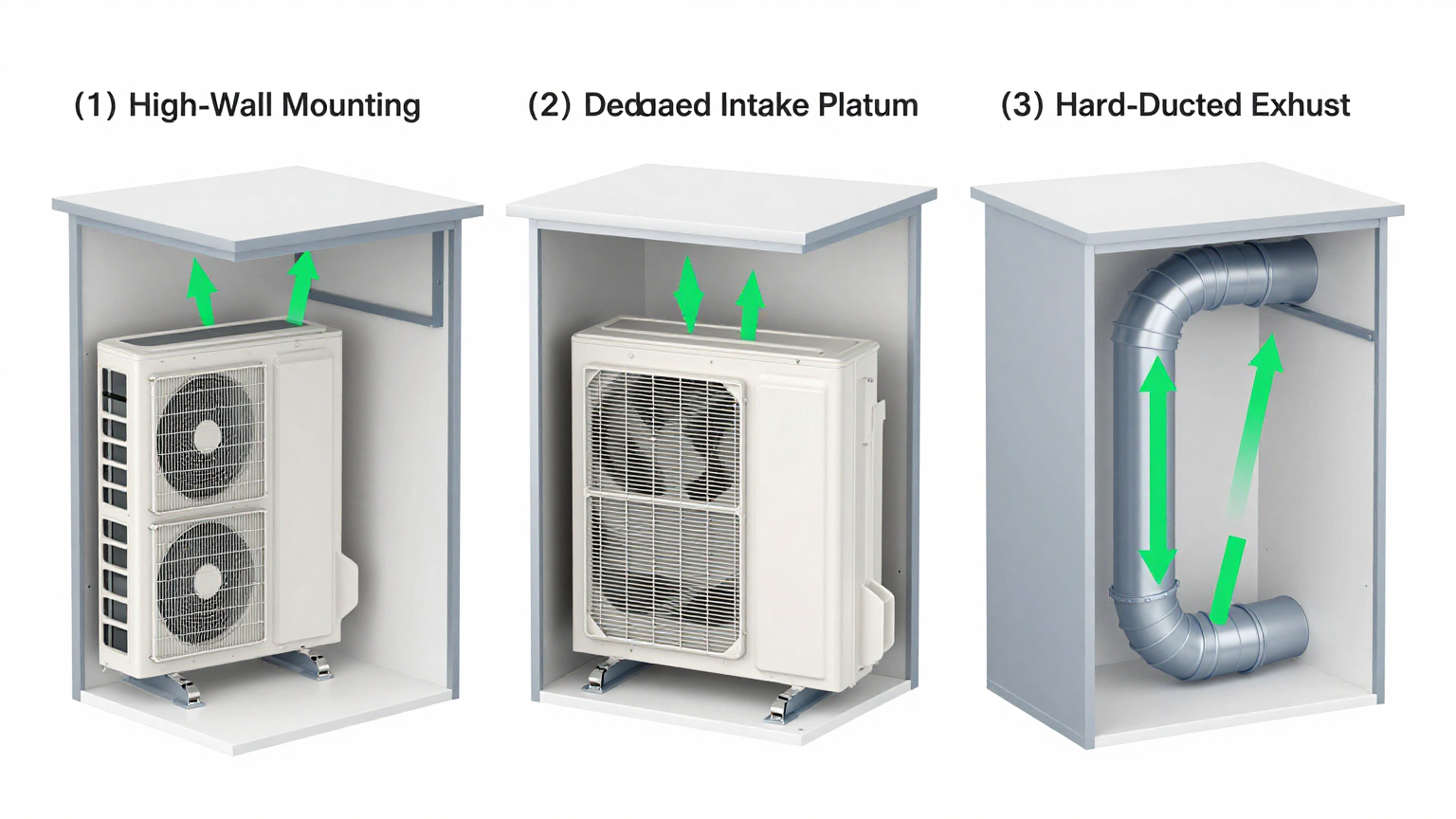

Strategy A: The “High-Wall” Intake

Instead of placing the unit on the floor where clutter (boots, bags, trash cans) blocks the intake, mount it on a sturdy shelf or bracket. RigidChill units are designed to withstand vibration, but ensure the shelf allows airflow from the bottom or sides, depending on the model’s intake grille location.

Strategy B: Dedicated Intake Plenums

If the unit must be boxed in or placed in a cabinet, you must install a dedicated intake vent. Cut a grille in the cabinet door directly in front of the AC’s intake. The grille area should be at least 1.5x the size of the AC’s intake filter to account for louver resistance.

Strategy C: Hard-Ducted Exhaust

Replace the flimsy flexible hose with smooth PVC or rigid metal ducting if the run is long. Smooth walls reduce friction loss, allowing the fan to push air further without overheating.

Conclusion: Give Your AC Room to Breathe

A portable DC air conditioner is a heat pump. It moves heat from inside to outside. If you block the air that carries that heat, the machine becomes nothing more than an expensive fan.

Before you blame the compressor or call for warranty service, grab a tape measure. If your unit is closer than 15cm to any wall, furniture, or box, you have likely found your problem. Clearing that gap is the cheapest repair you will ever make.

Integration support is available for custom deployments. If your guard booth has unique spatial constraints, our engineering team can review your floor plan and suggest optimal placement strategies.

Ready to equip your remote cabins? View the RigidChill Portable DC AC Series.

0 条评论