It is 11:00 AM on a remote survey site. The ambient temperature has already crossed 98°F, and the humidity is climbing. The crew lead opens the primary cooler to grab a recharge for the cooling vests, only to find a slurry of lukewarm water and half-melted gel packs. The “morning ice run”—which took a vehicle and a driver off-site for ninety minutes—has already been defeated by the thermal load. Now, the team faces a choice: continue working with diminishing thermal protection or halt operations to procure more ice. This scenario is the standard failure mode for passive cooling strategies in high-heat environments.

For safety managers and operations leads, the reliance on consumable thermal mass (ice, gel packs, soaked towels) represents a significant logistical tether. While low-tech solutions are accessible, they introduce variables that are difficult to control in dynamic field environments. As heat stress protocols tighten and operational windows shrink due to rising global temperatures, the shift toward active, iceless systems is becoming a necessary evolution for many industrial sectors. This field note explores the operational decision matrix when evaluating iceless cooling vs ice bath field operations, focusing on logistics, consistency, and safety integration.

Analyzing Iceless Cooling vs Ice Bath Field Operations in Remote Environments

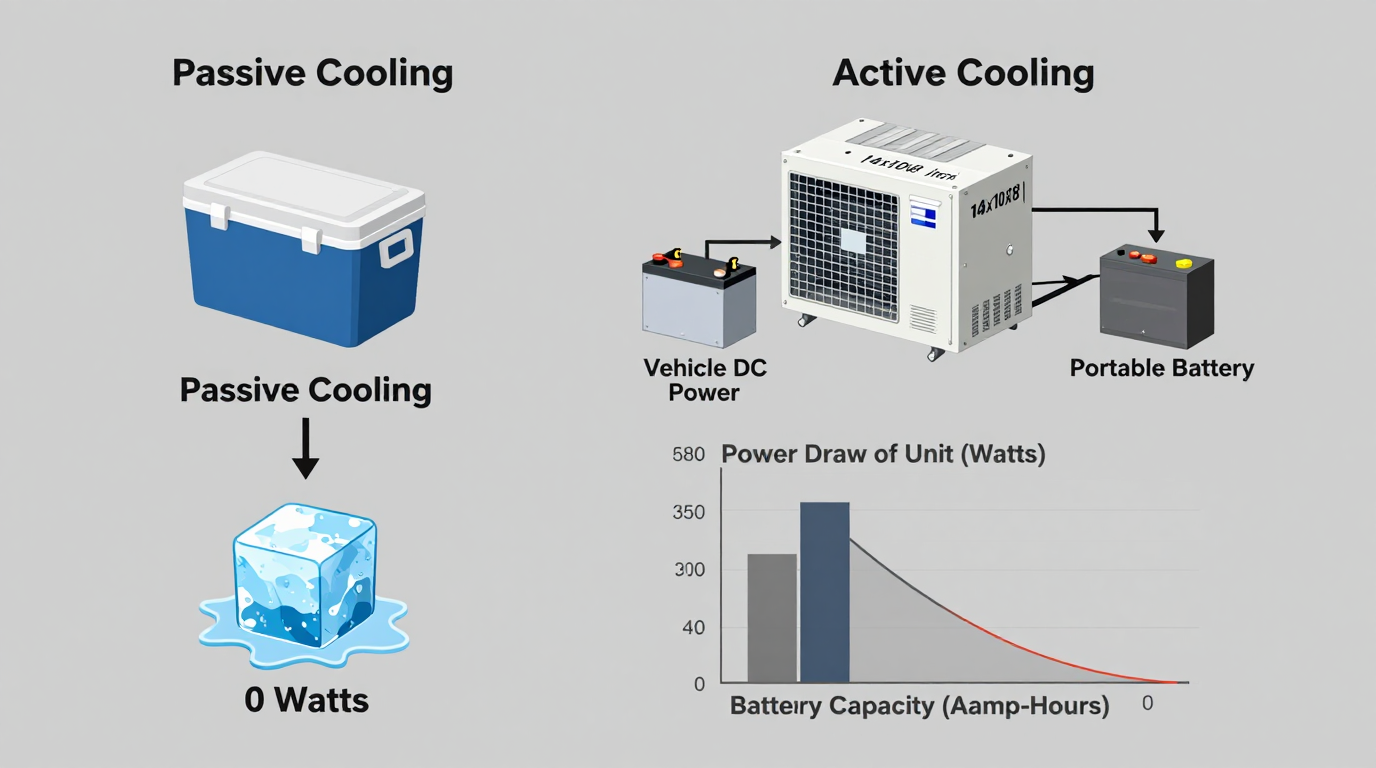

The fundamental difference between passive (ice-based) and active (iceless) cooling lies in the supply chain. Ice is a consumable resource that requires continuous replenishment. In a depot or warehouse setting, this may be manageable. However, in remote field operations—such as utility repair, mining, or tactical deployment—the “ice logistics” often consume disproportionate resources.

When comparing iceless cooling vs ice bath field operations, the first variable to audit is the “thermal supply chain.” Relying on ice requires a dedicated procurement cycle. If a crew is four hours from the nearest town, the ice must be transported in bulk, requiring valuable payload space and fuel. Furthermore, the cooling capacity of that ice begins to degrade the moment it leaves the freezer. By the time it is deployed, a significant percentage of its thermal energy has often been lost to the environment.

In contrast, an iceless system, such as the AlphaCooler, shifts the burden from consumables to power management. The constraint moves from “how much ice do we have?” to “what is our power budget?” For vehicles and sites with available DC power or generator capacity, this shift eliminates the need for mid-shift supply runs. The cooling capacity becomes indefinite as long as power is available, decoupling the crew’s safety from the proximity of a convenience store or ice plant.

The Weight Penalty and Payload Management

Every pound of gear on a truck or in a pack affects mobility and fuel efficiency. Ice is heavy. A standard cooler filled with enough ice and water to cool a four-person crew for a 10-hour shift can weigh significantly more than a compact, compressor-based cooling unit. Moreover, the weight of the ice system is “dead weight”—it provides no structural or functional benefit other than its thermal mass, which depletes over time.

Active cooling systems typically have a fixed weight. Whether the system runs for one hour or twenty hours, the mass of the compressor, pump, and heat exchanger remains constant. For fleet operators, this predictability allows for better suspension tuning and payload planning. There is no need to account for the variable load of 100 pounds of ice in the morning versus 100 pounds of water in the afternoon. The trade-off, however, is the requirement for permanent or semi-permanent mounting space and airflow clearance for the condenser, which must be factored into the vehicle upfit or site layout.

Thermal Consistency and the “Sawtooth” Effect

One of the critical engineering flaws of passive cooling is the lack of regulation. When a worker dons a vest fresh from an ice bath, the temperature is often near freezing (32°F / 0°C). This extreme cold can cause vasoconstriction, where the blood vessels in the skin tighten to preserve core heat. Paradoxically, this can inhibit the body’s ability to shed heat effectively, as blood flow is restricted away from the cooling surface.

As the ice melts or the towel warms, the cooling effect diminishes rapidly. This creates a “sawtooth” cooling profile: extreme cold followed by a rapid rise to ambient temperature, requiring another swap. This fluctuation forces the body to constantly adapt to changing thermal inputs, which can be physically taxing.

Active systems operate on a setpoint basis. A circulatory unit pumps fluid at a regulated temperature. This allows for a consistent thermal gradient that draws heat away from the body without inducing shock or vasoconstriction. The cooling is continuous and linear, maintaining efficacy throughout the entire duty cycle. For safety managers, this consistency simplifies the calculation of work/rest cycles. With ice, the protection factor degrades hour by hour; with active cooling, the protection factor remains constant, allowing for more predictable scheduling.

Hygiene and Biological Vectors in Shared Cooling

Field hygiene is often an overlooked aspect of thermal safety. In a traditional “ice bath” setup, crews often share a communal cooler to soak towels or recharge vest inserts. As the shift progresses, this water becomes a mixture of melted ice, sweat, road dust, and whatever particulate matter is on the workers’ PPE. In high-heat environments, this tepid, nutrient-rich water can become a breeding ground for bacteria.

Dipping a cooling towel into a communal slurry and then wrapping it around the neck—often near mucous membranes or minor abrasions—introduces a biological risk vector. This is particularly concerning in environments involving hazardous materials, wastewater, or chemical processing, where cross-contamination must be strictly controlled.

Iceless systems typically utilize closed-loop circulation. The coolant flows from the chiller unit to the vest and back without being exposed to the external environment. There is no “dipping” or sharing of fluids. Each worker connects to a manifold or has a dedicated loop, significantly reducing the risk of cross-contamination. Maintenance involves periodic flushing of the system rather than daily sanitization of a communal tub. For operations with strict hygiene protocols, this containment is often a deciding factor in the transition to active cooling.

Operational Downtime and the “Swap Cost”

The hidden cost of passive cooling is time. Consider the workflow of an ice vest:

1. The worker stops work.

2. They remove the vest or inserts.

3. They walk to the cooler.

4. They wait for the inserts to freeze or soak (if not prepped).

5. They re-gear and return to the task.

If this cycle repeats every 45 to 60 minutes in extreme heat, the cumulative downtime can amount to 15-20% of the shift. This “swap cost” disrupts flow and focus, particularly in tasks requiring sustained attention or complex assembly.

Active cooling systems are designed for tethered or semi-tethered operation, often allowing the worker to remain at the station. In vehicle-based operations (e.g., crane operators, armored vehicle drivers), the cooling is plumbed directly into the seat or vest, requiring zero downtime for thermal management. Even for mobile crews, quick-disconnect fittings allow for rapid attachment and detachment without the need to undress or swap internal components. The reduction in micro-breaks for cooling maintenance can yield measurable productivity gains, offsetting the initial capital expenditure of the equipment.

PPE Compatibility and Moisture Management

Wet cooling—such as soaked towels or evaporative vests—relies on evaporation. However, in high-humidity environments or under impermeable PPE (like Hazmat suits or heavy ballistic armor), evaporation is physically impossible. The air inside the suit is already saturated. In these conditions, a wet towel becomes a warm, wet compress that adds humidity to the microclimate inside the suit, potentially accelerating heat stress.

Ice vests function under PPE, but they introduce bulk and condensation. As the ice melts, condensation forms on the packs, often soaking the wearer’s base layers. Wet skin is more susceptible to chafing and fungal infections, especially during long shifts.

Circulatory iceless systems use dry heat exchange. The fluid is contained within tubing or bladders, and the cooling effect is conductive, not evaporative. This makes them compatible with completely sealed PPE ensembles. The system removes heat from the suit interior and rejects it outside via the chiller unit. Because the coolant temperature can be regulated above the dew point (if necessary), condensation can be managed or minimized, keeping the worker drier and more comfortable. This “dry cooling” capability is essential for electrical work, chemical handling, or any application where moisture is a liability.

Power Budget and Integration Constraints

While the benefits of iceless cooling are clear, the integration requires careful power planning. An ice chest requires zero watts; an AlphaCooler requires a reliable DC power source. For vehicle integrators, this means calculating the alternator headroom and battery capacity. If the engine is off, how long can the cooling run before draining the starter battery? In many cases, auxiliary battery banks or shore power connections are required for stationary operation.

The decision often comes down to the “energy density” of the mission. If the vehicle has ample power generation (common in utility trucks, military platforms, and emergency response vehicles), the power draw of a compressor is negligible compared to the operational uptime gained. However, for man-portable applications where a soldier or technician must carry the power source, battery weight becomes the limiting factor. In these scenarios, the trade-off between battery weight (for the chiller) and ice weight (for the vest) must be calculated based on mission duration. Typically, for missions exceeding 2-3 hours, the energy density of batteries driving a high-efficiency compressor surpasses the thermal density of ice.

Integration Support

Transitioning from passive to active cooling involves more than just buying a unit; it requires mapping the workflow, power availability, and mounting constraints of your specific fleet or site. If your operational profile involves extended durations in remote areas where ice logistics are breaking down, we can review your power budget and vehicle layouts to determine the viability of a circulatory system.

The shift to iceless cooling is a shift toward predictability. By removing the variables of melting rates and supply runs, safety managers can establish a baseline of thermal protection that holds up regardless of the shift length or ambient spikes.

0 条评论