The Environmental Adversary: Why Standard Cooling Fails in Extremes

For system integrators and OEM engineers, the “outdoor” label on a specification sheet is often deceptively simple. It masks the vast divergence between a deployment in a dry, high-heat desert and one in a saturated, corrosive tropical coast. While both environments threaten electronics, they do so through fundamentally different mechanisms. A cooling strategy that survives the Mojave may fail catastrophically in Singapore, not because of a lack of cooling power, but because of a failure to address the specific nature of the atmospheric load.

The challenge for technical buyers is to select a thermal management system that addresses these specific environmental aggressors without over-engineering the solution. In many remote or mobile applications—such as telecom repeaters, environmental sensors, or off-grid control cabinets—power budgets are tight, often limited to battery or solar arrays. Here, the selection of a micro ac for outdoor electronics cabinet integration becomes a balance of coefficient of performance (COP), physical footprint, and ingress protection.

This article analyzes the engineering constraints of desert versus tropical deployments. We will examine the failure modes specific to each, the limitations of passive or semi-passive cooling, and the role of active DC vapor-compression systems in maintaining uptime. The goal is to provide a defensible logic path for selecting thermal management components that align with harsh environmental realities.

Deployment Context: Two Extremes, One Uptime Requirement

To understand the necessity of active cooling, we must first define the boundary conditions of the deployment. In engineering terms, “harsh” is too vague. We need to look at the specific thermodynamic and physical stressors.

Scenario A: The High-Ambient Desert Deployment

Consider a remote telemetry station or a solar battery cabinet in a desert environment.

The Constraints:

- Ambient Temperature: Air temperatures frequently exceed 45°C or 50°C.

- Solar Loading: Direct sunlight adds a significant radiant heat load, potentially raising the internal cabinet temperature 15°C to 20°C above ambient if unshielded.

- Particulates: Fine dust and sand are omnipresent.

- Humidity: Extremely low. Condensation is rarely the primary concern; heat rejection is.

In this scenario, the primary enemy is the lack of “temperature headroom” (Delta T) for rejecting heat. If the internal electronics (e.g., Li-ion batteries) must remain below 35°C, but the outside air is 45°C, passive convection or fan-based cooling is physically unable to cool the cabinet. Heat flows from hot to cold; without an active cycle to reverse this, the cabinet will inevitably overheat.

Scenario B: The Tropical or Maritime Deployment

Consider a roadside traffic control cabinet or a marine sensor node in a tropical zone.

The Constraints:

- Ambient Temperature: Moderate, often 30°C to 35°C.

- Humidity: Relative Humidity (RH) often exceeds 80–90%.

- Corrosives: Salt spray or industrial pollutants are dissolved in the moisture.

- Biologicals: Mold and fungus growth can bridge circuits.

Here, the ambient temperature might theoretically allow for fan cooling if the internal limit is 55°C. However, introducing outside air brings in moisture and salt. As temperatures fluctuate (day/night cycles), the internal air hits the dew point, leading to condensation on PCBs. The failure mode here is not thermal shutdown, but short circuits and corrosion. A sealed enclosure is often required, necessitating a closed-loop cooling solution.

Decision Matrix: Selecting the Right Thermal Strategy

Engineers often weigh three main technologies for these scenarios: Filtered Fans (Open Loop), Thermoelectric Coolers (Peltier/TEC), and Micro DC Air Conditioners (Compressor-based). The following matrix compares these options against critical engineering criteria.

| Criteria | Filtered Fans (Open Loop) | Thermoelectric (TEC) | Micro DC Aircon (Compressor) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Ambient Cooling | Impossible (Always T_internal > T_ambient) | Yes (Limited capacity) | Yes (High capacity) |

| Sealed Enclosure (NEMA/IP) | No (Air exchange required) | Yes (Closed loop) | Yes (Closed loop) |

| Dust/Humidity Tolerance | Low (Filters clog; moisture enters) | High (No ingress) | High (No ingress + Dehumidifies) |

| Power Efficiency (COP) | High (Low draw, but no active cooling) | Low (Typically COP < 0.6) | High (Typically COP > 2.0 – 3.0) |

| Heat Load Suitability | Low to High (Depends on Delta T) | Low (Typically < 200W) | Medium to High (100W – 900W+) |

| Best-Fit Scenario | Indoor / Clean / Cool Ambient | Small enclosures / Low heat load | Outdoor / Harsh / High Heat or Humidity |

Implication: While fans are energy-efficient, they disqualify themselves in environments where T_ambient > T_target or where sealing is required. TECs offer sealing but often struggle with the power budget required to move significant heat loads (low COP). For deployments requiring 300W–500W of cooling with limited power (DC), the compressor-based micro air conditioner typically offers the most balanced performance.

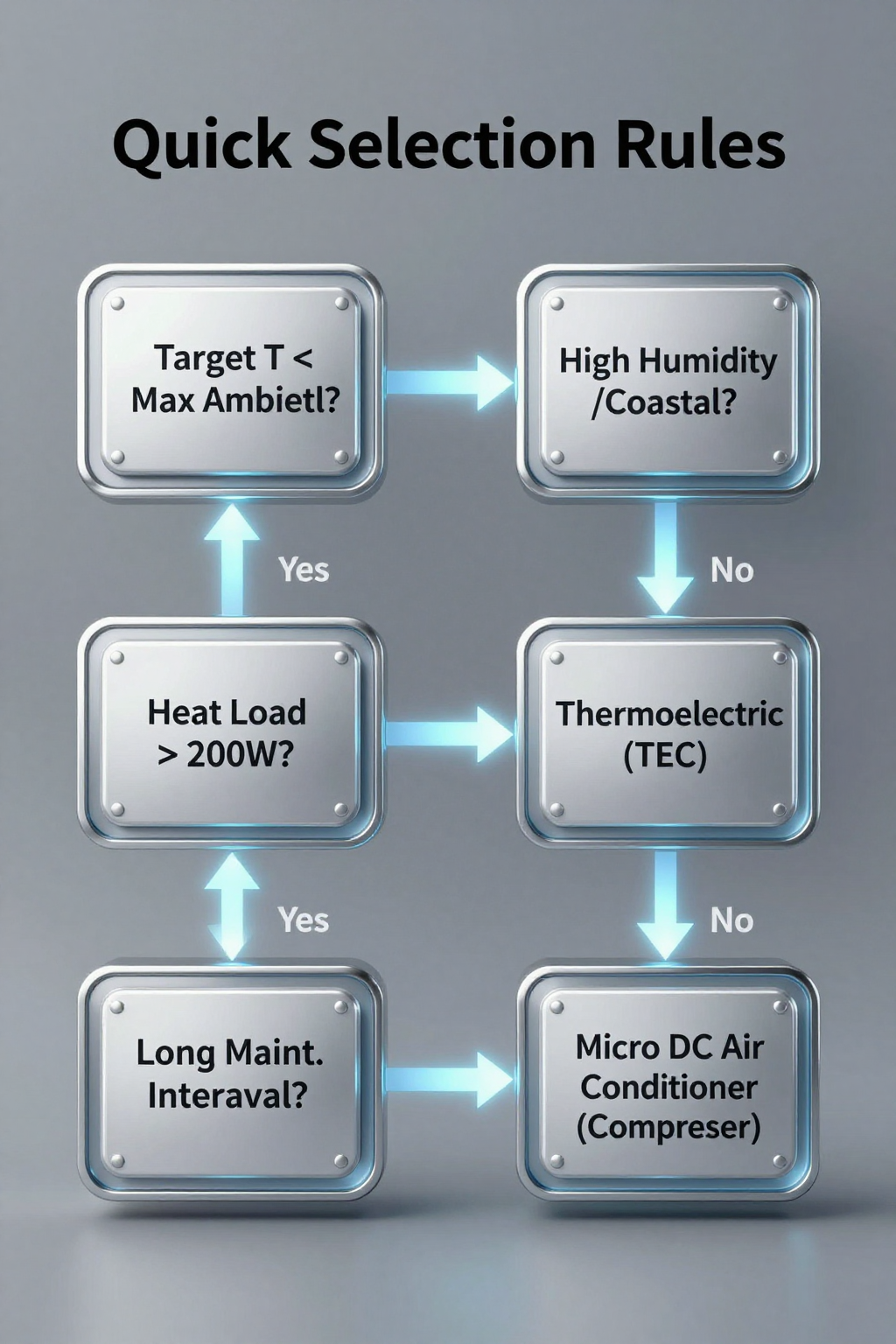

Quick Selection Rules

When reviewing a design, apply these logic checks to determine if active cooling is required:

- Rule 1: If the target internal temperature is lower than the maximum ambient temperature, you need active cooling (Compressor or TEC). Fans cannot cool below ambient.

- Rule 2: If the deployment is in a coastal or high-humidity zone, you typically need a closed-loop system to prevent salt/moisture ingress.

- Rule 3: If the heat load exceeds ~200W and the power source is battery/solar, a compressor system is usually preferred over TEC due to significantly higher efficiency (less battery drain per watt of cooling).

- Rule 4: If the maintenance interval must exceed 6 months in a dusty environment, avoid filter-based systems that require frequent cleaning to maintain airflow.

- Rule 5: If the enclosure contains batteries, prioritize keeping them near 25°C to preserve cycle life, which often necessitates active cooling even in moderate climates.

Failure Modes: The Unseen Enemies of Uptime

Understanding why systems fail helps justify the investment in robust thermal management. In outdoor electronics, failure is rarely a sudden explosion; it is usually a slow degradation caused by environmental stress.

1. The Thermal Throttle (Desert Mode)

In high-heat environments, modern processors and power electronics have built-in self-preservation mechanisms. As the internal temperature rises, the CPU throttles its clock speed to reduce heat generation.

The Result: The system doesn’t “break” immediately, but performance degrades. Data transmission slows, latency increases, and the system behaves erratically. Eventually, if the temperature continues to rise, the thermal limit switch trips, causing a hard shutdown. For remote sites, this means downtime until nightfall cools the cabinet.

2. The Battery Death Spiral (Heat Mode)

Lead-acid and Lithium-ion batteries are extremely sensitive to temperature. The Arrhenius equation suggests that for every 10°C rise in temperature, the rate of chemical reaction doubles. In a battery, this parasitic reaction degrades the internal chemistry.

The Result: A battery bank rated for 5 years at 25°C might last only 1–2 years if consistently operated at 45°C. This introduces massive OPEX costs for replacement truck rolls.

3. The Filter Choke (Dust Mode)

Fan-based systems rely on high airflow. To keep dust out, they use filters. In a desert environment, these filters load with particulate matter rapidly.

The Result: As the filter clogs, static pressure increases and airflow drops. The cooling capacity of the fan system plummets just when it is needed most. Without a technician to physically clean the filter, the cabinet overheats.

4. The Electrochemical Migration (Tropical Mode)

In humid environments, if outside air enters the cabinet, moisture condenses on cool surfaces. If that surface is a PCB, the water can dissolve ionic contaminants (dust, flux residue).

The Result: Under a voltage bias, these ions migrate, forming dendritic growth between traces. This leads to intermittent short circuits, “ghost” signals, and eventual permanent board failure.

Engineering Fundamentals: The Vapor Compression Advantage

To combat these failure modes, the industry often turns to the vapor compression cycle—the same physics found in residential AC, but miniaturized for DC-powered electronics. Unlike fans, which merely move air, a vapor compression system uses a refrigerant to absorb and reject heat, allowing it to cool below ambient temperature.

The Concept of Temperature Headroom

Heat transfer is driven by the temperature difference (Delta T) between the heat source and the cooling medium. In a desert where the air is 50°C, a passive heat sink has zero “headroom” to cool a 50°C component. A compressor system creates an artificial cold spot (the evaporator), often at 10°C–15°C. This restores the Delta T, allowing heat to flow out of the electronics and into the refrigerant, which then pumps it outside.

Latent Heat and Dehumidification

In tropical environments, the ability to handle latent heat (moisture) is critical. As air passes over the cold evaporator coil of a micro DC air conditioner, its temperature drops below the dew point. Water vapor condenses into liquid and is drained away. This process actively dries the air inside the sealed cabinet.

Why this matters: By lowering the internal relative humidity, you eliminate the risk of condensation on sensitive electronics, even if the outside air is saturated.

Sealing and Ingress Protection

A critical advantage of this approach is the ability to maintain a “closed loop.” The air inside the cabinet circulates through the evaporator but never mixes with the outside air. This allows the enclosure to maintain high NEMA or IP ratings (e.g., IP55, IP65).

Reality Check: Closed-loop designs avoid air exchange, but overall ingress protection still depends on gasket integrity, cable glands, and installation quality. A micro AC unit cannot fix a cabinet that has holes drilled in the bottom for loose cabling.

Performance Data & Verified Specs

When selecting a Micro DC Aircon, engineers should look for verified specifications that match their power availability and heat load. The following table highlights typical parameters for the DV series, a common reference for miniature DC cooling.

| Parameter | DV1910E-AC (Pro) | DV1920E-AC (Pro) | DV1930E-AC (Pro) | DV3220E-AC (Pro) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC Voltage | 12V | 24V | 48V | 24V |

| Nominal Cooling Capacity | 450W | 450W | 450W | 550W |

| Refrigerant | R134a | R134a | R134a | R134a |

| Compressor Type | Miniature BLDC Inverter Rotary | Miniature BLDC Inverter Rotary | Miniature BLDC Inverter Rotary | Miniature BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| Control | Integrated Driver Board | Integrated Driver Board | Integrated Driver Board | Integrated Driver Board |

Note: Cooling capacity varies based on operating conditions (evaporating/condensing temperatures). The values above represent nominal ratings.

These units utilize a variable-speed BLDC inverter compressor. This is significant for off-grid applications because it avoids the massive “inrush current” spikes associated with traditional on/off AC compressors. The system can soft-start and ramp up to meet the load, which is gentler on battery banks and power supplies.

Field Implementation Checklist

Successful integration requires more than just bolting a unit to a cabinet. Based on field experience, here is a checklist for system designers:

Mechanical Integration

- Airflow Management: Ensure the “cold air out” path from the AC unit is not blocked by cabling or equipment. Short-cycling (where cold air is immediately sucked back into the intake) will cause the unit to cycle off prematurely while the rest of the cabinet remains hot.

- Condensate Management: In tropical environments, the unit will generate water. Ensure the drain tube is routed correctly to the outside and includes a trap or valve to prevent insects/dust from entering.

- Gasket Compression: Check that the mounting flange gasket is evenly compressed to maintain the IP rating of the enclosure.

Electrical Integration

- Cable Sizing: DC systems are sensitive to voltage drop. Undersized cables can cause the voltage at the compressor driver to dip below the cutoff threshold during high-load operation, causing nuisance faults.

- Circuit Protection: Always use a fuse or breaker rated for the maximum current draw of the unit, placed as close to the power source as possible.

Thermal Optimization

- Solar Shielding: A simple sunshade over the cabinet can reduce the solar heat load by 50% or more. This reduces the work the active cooling system must do, saving energy.

- Insulation: Insulating the cabinet walls helps stabilize the internal temperature and reduces the cooling load, further improving efficiency.

Expert Field FAQ

Q: Can I run a Micro DC Aircon directly from a solar panel?

A: Typically, no. While they are DC-native, they require a stable voltage source. The output of a solar panel fluctuates wildly. The unit should be powered by the battery bank or a regulated DC bus that is charged by the solar panels.

Q: How does the maintenance interval compare to fan filters?

A: It is generally much longer. Since the enclosure is sealed, there are no internal filters to clean. The external condenser coil may need occasional cleaning (compressed air or brush) if dust accumulation is extreme, but it is far more tolerant of blockage than a filter mesh.

Q: What happens if the ambient temperature exceeds the unit’s rating?

A: Most compressor systems have a high-pressure cutoff. If the outside air is too hot for the condenser to reject heat effectively, the pressure rises, and the system will shut down to protect itself. However, tropical versions (like the T-series compressors) are designed for higher ambient limits.

Q: Does the unit run 100% of the time?

A: Not usually. With an inverter driver, the compressor can vary its speed to match the heat load. If the load is low (e.g., at night), it slows down or cycles off, conserving power.

Q: Can I use this for a battery cabinet?

A: Yes, this is a common application. Batteries often require a narrower temperature range (e.g., 20°C–30°C) than rugged electronics. Active cooling is often the only way to maintain this range in outdoor environments.

Q: Is R134a the only refrigerant option?

A: While R134a is standard for many models like the DV1910E-AC, other options like R290 and R1234yf are becoming available in certain series to meet evolving environmental regulations.

Conclusion: The Logic of Active Cooling

The decision to integrate a micro ac for outdoor electronics cabinet systems is ultimately a calculation of risk and lifecycle cost. For benign environments, passive methods may suffice. But for the extremes—the scorching heat of the desert or the saturated air of the tropics—passive methods often cross the line from “simple” to “inadequate.”

By selecting a closed-loop, active cooling solution, engineers decouple the internal electronics from the external environment. This strategy provides the temperature headroom necessary to prevent thermal shutdown and the sealing necessary to prevent corrosion. While the upfront complexity is higher than a fan, the reduction in truck rolls, battery replacements, and downtime often yields a positive ROI within the first year of operation.

Whether you are designing a DC enclosure air conditioner harsh environment solution or a compact mobile rig, the physics remain the same: you must move heat, not just air.

Requesting a Sizing Consultation

To ensure you select the correct capacity for your deployment, accurate sizing is critical. When contacting our engineering team for a consultation, please have the following inputs ready to ensure a rapid and defensible recommendation:

- Target Internal Temperature: (e.g., “Must maintain <35°C”)

- Maximum Ambient Temperature: (e.g., “Up to 55°C in direct sun”)

- Heat Load Estimate: Total watts generated by internal equipment.

- Power Source: Voltage (12V/24V/48V) and current limits.

- Cabinet Dimensions & Insulation: H x W x D and material type.

- Sealing Requirement: Target IP or NEMA rating.

0 条评论