Why Sealed Cabinets Fail: A Guide to the Micro DC Air Conditioner in Humid Environments

In industrial automation, telecommunications, and outdoor digital signage, the premature failure of sensitive electronics is a costly problem. While overheating is a well-understood enemy, a more insidious threat often goes unnoticed until it’s too late: moisture. In deployments near coastal areas, on factory floors with high humidity, or in tropical climates, an electronics cabinet can become a perfect terrarium for condensation. The result is a cascade of failures, from intermittent faults and data corruption to catastrophic short circuits and board-level corrosion. The financial stakes aren’t just the cost of the components, but the operational downtime, service calls, and damage to brand reputation.

Engineers often face a critical decision: how to cool a sealed enclosure without compromising its integrity or introducing moisture. This article provides a data-driven framework for making that choice. We will dissect the physics of humidity, analyze the failure modes it causes, and walk through the engineering logic for selecting a reliable cooling solution. By the end, you will be able to determine when a closed-loop, active cooling system is not just an option, but a necessity for long-term reliability. In this analysis, we prioritize active moisture removal over simple heat exchange, because in high-humidity scenarios, managing the dew point is as critical as managing the temperature.

Deployment Context: Where Humidity Becomes the Primary Threat

Theoretical discussions fall short without real-world context. Here are two common scenarios where conventional cooling methods fail due to ambient humidity, forcing a design re-evaluation.

Scenario A: Coastal Substation Control Panel

A telecom provider deployed a series of sealed NEMA 4X cabinets housing control hardware for a coastal 5G network. The initial design used a large passive heat exchanger, deemed sufficient for the 250W internal heat load. However, within six months, intermittent system resets plagued the site. A field technician discovered visible moisture and early-stage corrosion on a secondary power distribution board. The cause wasn’t a leak; it was the daily temperature cycle. During the hot, humid day, the air inside the “sealed” cabinet still contained significant water vapor. At night, as the cabinet’s metal skin cooled rapidly, the internal air temperature dropped below its dew point, causing condensation directly onto the electronics.

Scenario B: Food Processing Plant Automation Cabinet

An automation integrator installed a series of stainless-steel IP66 cabinets on a food processing line. The environment required frequent high-pressure washdowns, making a perfect seal non-negotiable. To manage the heat from VFDs and PLCs, the design incorporated a high-CFM filtered fan kit, assuming the plant’s ambient air was climate-controlled. The fans kept temperatures in check, but they also continuously pulled in fine, moisture-laden air from steam-cleaning processes. This humid air, rich in microscopic organic particles and cleaning agents, created a conductive film on PCBs. The result was not immediate failure, but a creeping degradation of signal integrity and, eventually, a complete VFD failure due to a short circuit across its control terminals.

Failure Modes & Constraints in High-Humidity Deployments

When evaluating cooling for a humid environment, the risks extend beyond simple thermal throttling. The focus must shift to moisture-induced failures. Here are the most common failure modes, ranked by their potential for immediate or long-term damage.

- Catastrophic Short Circuit → Condensation forms on PCBs, creating a conductive path between traces, leading to immediate and permanent hardware failure.

- Galvanic Corrosion → Trapped moisture acts as an electrolyte between dissimilar metals on a circuit board, causing slow but irreversible trace and component lead degradation.

- Reduced Insulation Resistance → High humidity lowers the dielectric strength of PCB substrates and conformal coatings, increasing the risk of electrical leakage and signal noise.

- Phantom Faults & Data Corruption → Intermittent condensation or high humidity can alter the capacitance and resistance of circuits, causing unpredictable behavior that is difficult to diagnose.

- Accelerated Component Aging → Humidity is a known accelerator in component degradation, especially for optics, connectors, and certain types of capacitors, reducing the system’s mean time between failures (MTBF).

- Compromised Seal Integrity → Aggressive cooling/heating cycles can cause pressure differentials in a sealed cabinet, stressing gaskets and potentially drawing in moist air over time (breathing).

- Clogged Air Filters → In vented systems, high humidity causes dust and particulates to clump together, rapidly clogging filters, reducing airflow, and leading to overheating.

Engineering Fundamentals: Dew Point, Not Just Temperature

The core of managing electronics in a humid environment is understanding the concept of dew point. The dew point is the temperature at which air becomes saturated with water vapor and condensation begins to form. It is a function of both temperature and relative humidity. An engineer’s primary goal in a sealed cabinet is to ensure the surface temperature of any electronic component never drops to the dew point of the air inside the cabinet.

This leads to a critical, often-overlooked misconception. Many believe that as long as a cabinet is sealed, the internal humidity is static. This is incorrect. Every time the cabinet is opened for service, it is filled with ambient, humid air. Gaskets and cable glands are rarely perfect, allowing for slow moisture ingress over time. Therefore, the internal air must be treated as a potential liability.

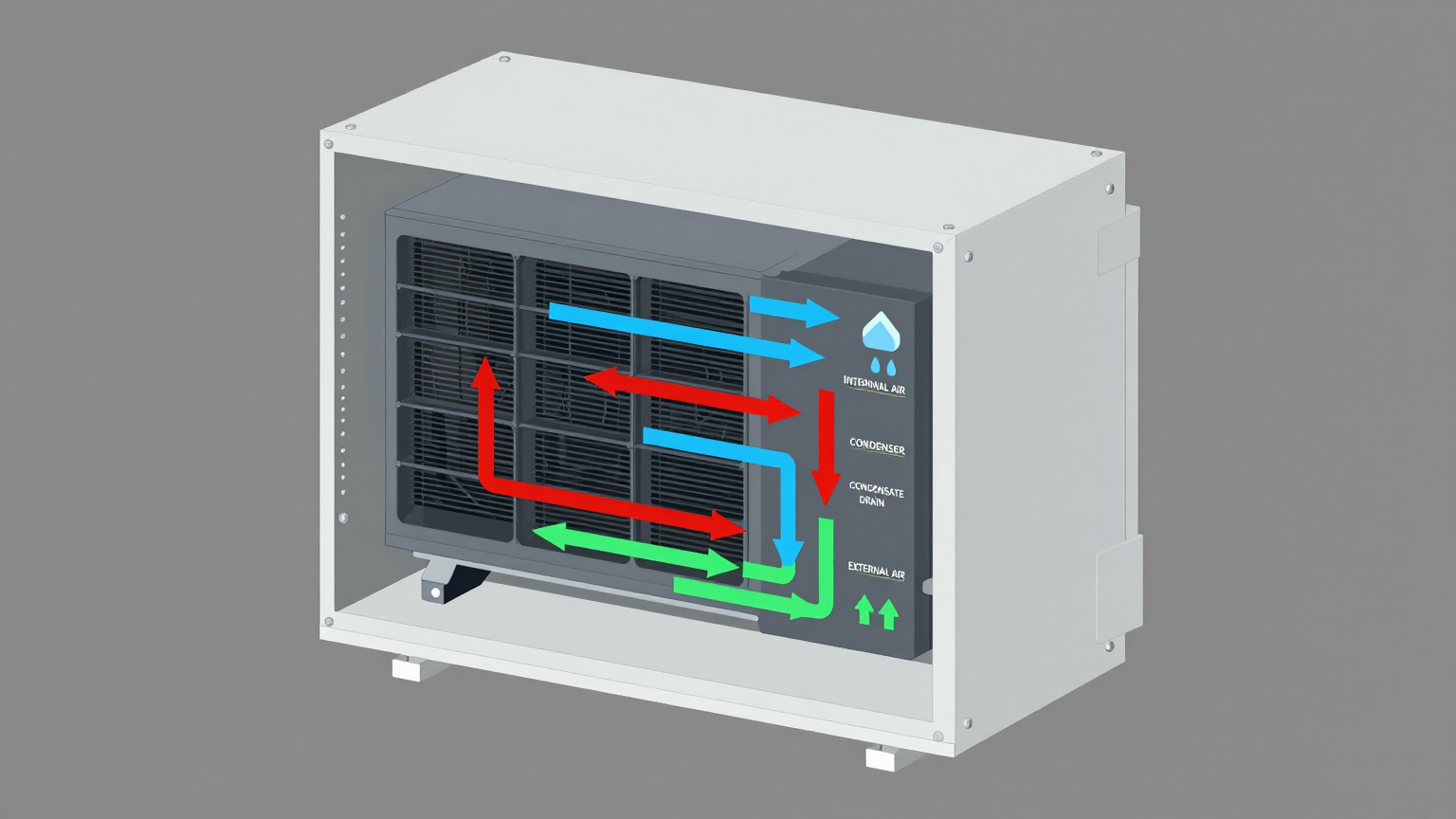

A micro DC air conditioner addresses this problem directly through its closed-loop vapor-compression cycle. Here’s how it works in this context:

- Internal Air Circulation (Closed Loop): The unit draws warm, moist air from inside the cabinet across its cold evaporator coil. It does not introduce any outside air.

- Cooling & Dehumidification: As the air passes over the evaporator, two things happen. Its temperature drops (sensible cooling), and more importantly, the moisture in the air condenses on the cold coil surface (latent cooling), effectively “squeezing” water out of the air.

- Condensate Management: This collected water is then drained to the outside of the enclosure, permanently removing the moisture from the internal environment.

- Heat Rejection: The heat absorbed from the internal air (plus the operational heat of the compressor) is transferred via the refrigerant to a condenser coil, where it is expelled into the ambient environment outside the cabinet.

This process actively lowers the dew point of the internal air, creating a dry, controlled microclimate that protects the electronics. A simple fan or heat exchanger cannot do this; they can only transfer heat and do nothing to remove the water vapor already trapped inside.

Key Specifications for Humid Environments

When selecting a micro DC air conditioner for a humid environment, certain specifications are non-negotiable. The table below shows example parameters from the Rigid Chill Micro DC Aircon series. How to read these specs for this specific decision: focus on the combination of cooling capacity and DC voltage. The capacity must be sufficient to handle your internal heat load plus any solar gain, while the voltage must match your system’s power bus (e.g., 12V, 24V, or 48V DC), which is common in telecom and off-grid applications.

| Model (Example) | Input Voltage | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC (Pro) | 12V DC | 450W | R134a |

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V DC | 450W | R134a |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V DC | 450W | R134a |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V DC | 550W | R134a |

Beyond the table, these factors are go/no-go gates for your project:

- Sealing (IP/NEMA Rating): The unit must be designed to mount to an enclosure while maintaining the overall system’s required IP (Ingress Protection) or NEMA rating. This ensures dust, water, and washdowns do not compromise the seal.

- Condensate Management: How does the unit dispose of the collected water? Look for robust, gravity-fed drain ports or, in some advanced units, evaporation systems. A blocked drain can be as bad as no dehumidification.

- Operating Temperature Range: The unit must be rated to operate reliably at the maximum expected ambient temperature of the deployment site.

- Power Consumption: The unit’s power draw at full load must fit within your DC power budget, especially for battery-powered or solar-powered sites.

- Control Logic: Does the unit have intelligent controls? Variable-speed compressors and fans are far more efficient than simple on/off systems, reducing power consumption and mechanical stress.

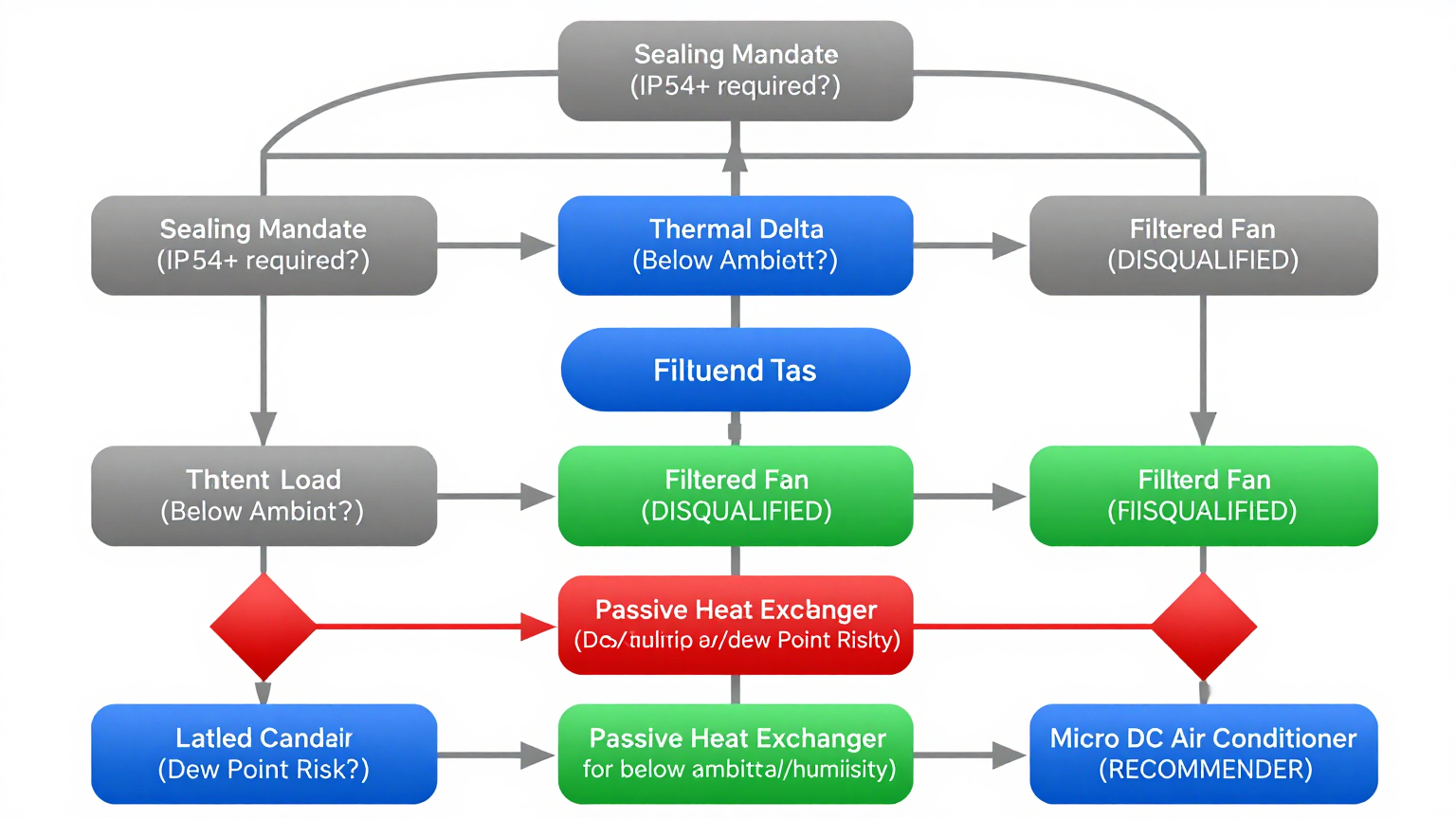

Engineering Selection Matrix: Logic Gates for System Integrators

Choosing the right cooling technology is a process of elimination based on hard constraints. An engineer must pass through several logic gates to arrive at a reliable solution for a sealed cabinet cooling moisture issues scenario.

Logic Gate 1: The Sealing Mandate

- The Constraint Gate: Environmental Exposure vs. Ingress Protection. The deployment environment dictates the required NEMA or IP rating. A dusty field requires dust-tightness (NEMA 12/IP5X), while an outdoor coastal site needs water and corrosion resistance (NEMA 4X/IP66).

- The Decision Trigger: If the enclosure requires a rating of IP54 or higher to protect against dust, water spray, or washdowns.

- Engineering Resolution: This immediately disqualifies any open-loop cooling solution, such as a simple filtered fan. Fans, by definition, create a path for ambient air—and all its contaminants and humidity—to enter the enclosure. The choice is now narrowed to closed-loop systems: passive heat exchangers or active air conditioners.

- Integration Trade-off: Committing to a sealed design increases upfront cost and complexity but is the only viable path to ensure the design life of the internal electronics in contaminated or wet environments.

Logic Gate 2: The Thermal Delta Requirement

- The Constraint Gate: Internal Target Temperature vs. Maximum Ambient Temperature. This is the fundamental thermal challenge.

- The Decision Trigger: If the required internal cabinet temperature must be maintained at or below the maximum external ambient temperature.

- Engineering Resolution: This is the point where passive heat exchangers become insufficient. A heat exchanger can only bring the internal temperature down to a few degrees *above* the ambient temperature. To go below ambient, or even hold a temperature equal to ambient against an internal heat load, you need active refrigeration. This makes a vapor-compression system like a micro DC air conditioner the necessary choice.

- Integration Trade-off: Moving to an active cooling solution introduces a higher DC power load and a more complex component. However, it provides deterministic thermal control, ensuring sensitive electronics do not derate or fail, regardless of external temperature swings.

Logic Gate 3: The Latent Load (Humidity) Risk

- The Constraint Gate: Ambient Relative Humidity vs. Internal Dew Point. This gate specifically addresses the risk of condensation.

- The Decision Trigger: If the deployment is in a region with sustained relative humidity above 70% RH, or if there are rapid temperature drops (e.g., day/night cycles in a desert or after a rainstorm).

- Engineering Resolution: Even if a heat exchanger can handle the thermal load (Gate 2), it cannot manage the latent load (moisture). By circulating the internal air, it does nothing to remove the water vapor trapped inside. A dc enclosure air conditioner high humidity solution is designed for this. Its evaporator coil actively pulls moisture from the air, reducing the internal relative humidity and drastically lowering the dew point, making condensation a non-issue.

- Integration Trade-off: This requires planning for condensate drainage, which adds a minor mechanical integration step. However, this single step eliminates the primary cause of moisture-related electronic failures, directly increasing system MTBF. For more information on compact solutions, see our overview of Micro DC Aircon products.

Implementation Checklist for Reliability

Proper installation is as important as correct selection. A poorly integrated unit can fail to protect the system. Follow this checklist for a robust deployment.

-

Mechanical Integration

- Gasket Seal: Ensure the mounting gasket provided with the air conditioner is compressed evenly. Torque mounting bolts to the manufacturer’s specification. The seal between the unit and the cabinet wall is the most critical point of potential moisture ingress.

- Airflow Paths: Verify there is unobstructed clearance for both the internal (cold) and external (hot) airflows. Do not allow cables or other components to block the unit’s inlets or outlets. A common mistake is placing a tall component directly in front of the cold air discharge, preventing proper circulation within the cabinet.

- Condensate Drain: Install the drain tube with a continuous downward slope, avoiding any loops or kinks where water could pool. Ensure the outlet is not positioned where it could be blocked by debris or ice.

-

Electrical Integration

- Wire Gauge & Fusing: Use the recommended wire gauge for the DC power supply to prevent voltage drop, especially over long runs. Install an appropriately rated fuse or circuit breaker as close to the power source as possible.

- Power Stability: Ensure the DC power source is stable and free from excessive noise or voltage sag. A poor-quality power supply can damage the air conditioner’s sensitive control electronics.

- Control Wiring: If using remote alarms or controls, ensure wiring is shielded if routed near high-power cables (like VFD outputs) to prevent electromagnetic interference.

-

Thermal Validation

- Sensor Placement: Place monitoring thermocouples or sensors near the top of the cabinet (where hot air collects) and near the most sensitive electronic components, not directly in the air conditioner’s cold air stream. This gives a true reading of cabinet conditions.

- Acceptance Test: After installation, run the system under full load. Let the cabinet temperature stabilize and verify that it remains below the target maximum. If possible, perform this test on a hot, humid day to validate performance under worst-case conditions.

-

Maintenance Planning

- Condenser Coil Cleaning: The external (hot side) condenser coils are the system’s radiator. In dusty or dirty environments, they must be inspected and cleaned periodically to ensure efficient heat transfer. Clogged coils will reduce cooling capacity and increase power consumption.

- Gasket Inspection: During routine site visits, visually inspect the mounting gasket for signs of degradation, especially in environments with high UV exposure or chemical contaminants.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can’t I just use a thermoelectric (Peltier) cooler for my sealed cabinet?

Thermoelectric coolers can work for small heat loads in moderately humid environments. However, they are significantly less efficient than vapor-compression systems, meaning they consume more power for the same amount of cooling. More importantly, their cold side can easily drop below the dew point, causing condensation *inside* the unit itself if not properly managed, which can be a reliability risk in very humid conditions.

2. What if my cabinet must be IP67 or fully submersible?

Standard cabinet air conditioners are typically rated up to IP66/NEMA 4X. For higher ratings like IP67, a custom solution is often required. This may involve specialized gaskets, sealed connectors, and pressure equalization valves. It’s critical to discuss these requirements with the cooling unit manufacturer during the design phase.

3. How do I manage condensation if my electronics generate very little heat?

This is a classic electronics cabinet condensation risk scenario. If there’s little internal heat, the cabinet temperature can easily track the ambient temperature. When the outside temperature drops quickly at night, condensation can form inside. A micro DC air conditioner with a thermostat will activate not just on heat, but also to maintain a stable temperature, and its dehumidifying effect will keep the internal air dry, preventing this problem.

4. What is the impact of direct sun exposure on the cooling unit?

Direct solar radiation adds a significant heat load to the enclosure. This “solar load” must be calculated and added to the internal electronic heat load when sizing the air conditioner. A solar shield or placing the cabinet in a shaded location is highly recommended to reduce the burden on the cooling system and lower energy consumption.

5. What is the first measurement I must take before selecting a cooling unit?

The two most critical measurements are the total internal heat load (in watts) generated by all components inside the cabinet, and the maximum expected ambient temperature at the deployment site. Without these two data points, any cooling calculation is just a guess.

6. How can I validate that the system is working correctly after installation?

The best validation method is to use a data logger to record the internal cabinet temperature and humidity over a 24-48 hour period that includes the peak heat of the day. Compare this data to the external ambient conditions. A successful installation will show a stable internal temperature below your setpoint and a significantly lower internal relative humidity compared to the outside air.

Conclusion: The Right Tool for a Demanding Job

For electronic systems deployed in challenging locations, assuming that “cool enough” is “safe enough” is a flawed strategy. In coastal, tropical, or industrial washdown environments, humidity is an active threat that can and will cause failures. While simple fans and passive heat exchangers have their place, they are fundamentally incapable of managing moisture in a sealed enclosure.

The best-fit solution for this challenge is a closed-loop, active refrigeration system. A micro DC air conditioner in a humid environment is not just a cooler; it is a microclimate controller. By actively cooling and dehumidifying the air within a sealed cabinet, it directly mitigates the primary risks of condensation and corrosion. This approach moves beyond simple thermal management to deliver true environmental protection, ensuring the reliability and longevity of the critical electronics inside. When system uptime is non-negotiable and the environment is unforgiving, investing in active condensate management is a sound engineering decision.

If you are designing a system for a high-humidity deployment, our engineering team can help you calculate the specific thermal and latent loads to ensure a properly sized and configured solution. Contact us to discuss your project’s unique constraints, from power budgets to custom mounting requirements.

0 条评论