The Forensic Path: Why Validation Fails Before the First Test

Reliability engineering is rarely about checking boxes on a datasheet; it is about anticipating the physics of failure in environments that do not forgive design oversights. When a sealed enclosure overheats in a remote deployment, the root cause is almost never a mystery to the forensic engineer—it is usually a misalignment between the lab simulation and the chaotic reality of the field. The cooling system did not fail; the assumptions regarding the thermal load, solar gain, or power availability failed.

For Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and system integrators deploying assets in harsh, off-grid, or mobile environments, the stakes are high. A thermal shutdown in a desert telecom repeater or a mobile medical transport unit results in expensive truck rolls, downtime penalties, and potential component degradation. The only defense against these outcomes is a rigorous, defensible micro DC air conditioner validation test that moves beyond nominal specs and stresses the integration under realistic constraints.

This guide outlines a practical, data-driven approach to validating active cooling solutions for sealed cabinets. We will bypass marketing hype to focus on the thermal and electrical behaviors that actually determine uptime. Whether you are integrating a 12V system for a vehicle or a 48V system for a solar-powered tower, the physics of heat rejection remain the primary adversary.

Deployment Context: Where Theory Meets Thermodynamics

To understand why standard validation often falls short, we must look at the specific constraints of the deployment environments where micro DC air conditioners are typically utilized. These are not climate-controlled server rooms; they are dynamic, hostile edges of the network.

Scenario A: The Off-Grid Telecom Node

Consider a remote sensor station or telecom repeater located in an arid region. The enclosure is exposed to direct solar loading, pushing the internal temperature well above the ambient air temperature. The power source is a battery bank charged by solar arrays, meaning the energy budget is finite.

Constraints:

• Ambient Temperature: Often exceeds 45°C or 50°C during peak daylight.

• Power Source: 48V DC battery bank with strict autonomy requirements.

• Maintenance: Sites are visited perhaps once or twice a year.

• Challenge: The cooling unit must reject heat without draining the battery faster than the solar array can replenish it. A compressor that runs continuously due to poor insulation or undersizing will trigger a low-voltage disconnect (LVD), taking the site offline.

Scenario B: The Mobile Medical Transport

In this scenario, a sealed cabinet houses sensitive diagnostic equipment inside an ambulance or transport van. The vehicle’s electrical system fluctuates, and vibration is a constant stressor.

Constraints:

• Voltage Stability: 12V or 24V DC alternator power, subject to spikes and sags.

• Airflow: The cabinet is often tucked into a tight space with poor external circulation.

• Vibration: Constant road shock requires robust mounting and piping resilience.

• Challenge: The cooling system must maintain a precise internal temperature to preserve reagents or electronics, regardless of the vehicle’s engine state or cabin temperature.

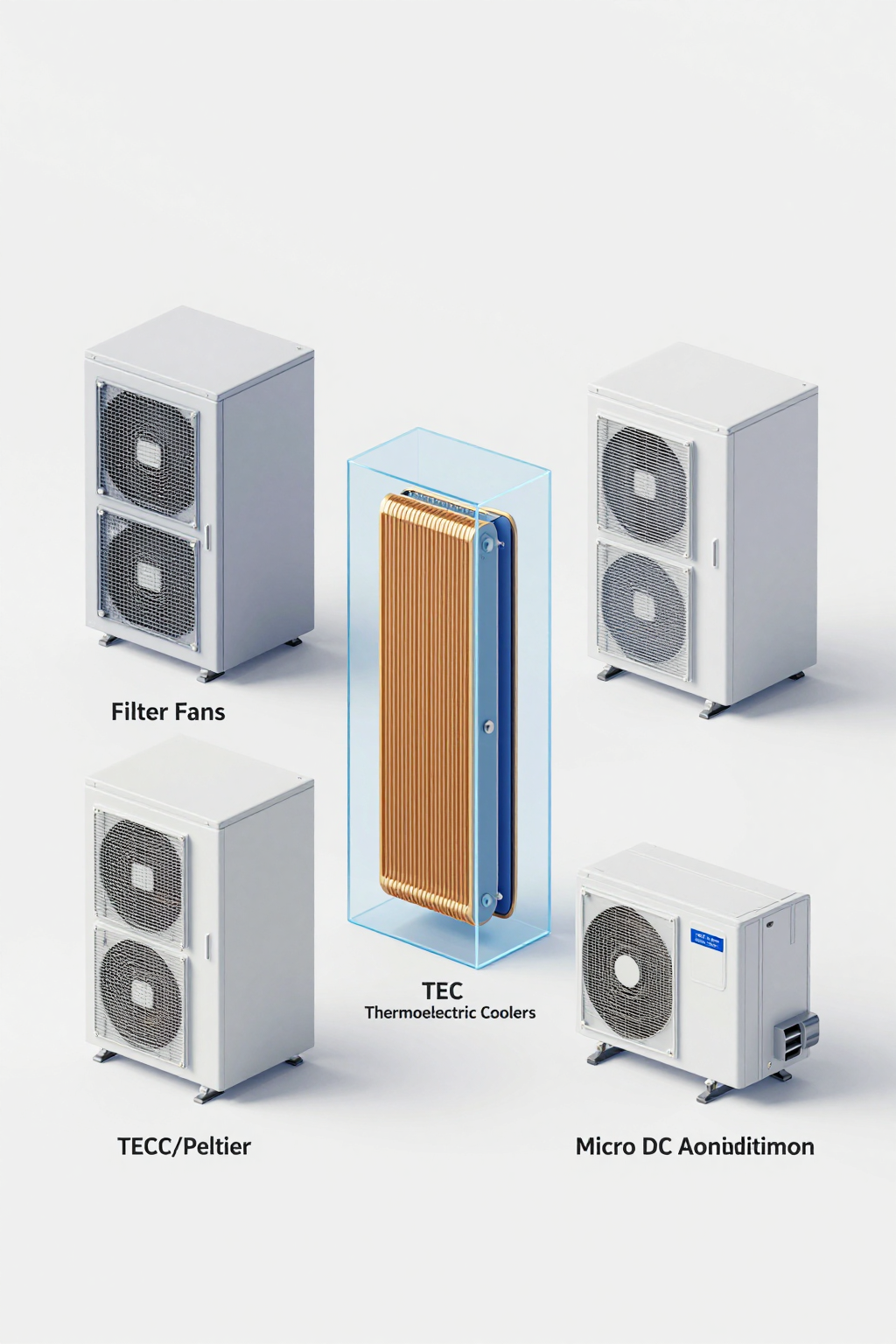

Decision Matrix: Selecting the Right Thermal Strategy

Before drafting a micro DC air conditioner validation test plan, engineers must confirm that active cooling is the correct architectural choice. The table below compares common thermal management technologies against the criteria that matter most in harsh deployments.

| Criteria | Open-Loop Fans | Thermoelectric (TEC/Peltier) | Micro DC Aircon (Compressor) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Ambient Cooling | Impossible (Physics limit) | Yes (Limited capacity) | Yes (High capacity) |

| Sealed Enclosure (NEMA/IP) | No (Requires air exchange) | Yes (Closed loop) | Yes (Closed loop) |

| Dust/Humidity Tolerance | Low (Filters clog) | High (No ingress) | High (No ingress) |

| Power Efficiency (COP) | High (Low power draw) | Low (Inefficient at high loads) | High (Vapor compression efficiency) |

| Heat Load Suitability | Low to Medium (Depends on Delta T) | Low (< 200W typically) | Medium to High (100W–900W+) |

| Best-Fit Scenario | Indoor, clean, T_internal > T_ambient | Small enclosures, low heat, vibration sensitive | Outdoor, hot ambient, high heat load |

Implication: If your application requires the internal temperature to be lower than the outside air (sub-ambient cooling) or demands a strictly sealed enclosure to prevent dust ingress, open-loop fans are physically incapable of meeting the requirement. While TECs offer a solid-state solution, their low Coefficient of Performance (COP) often disqualifies them for battery-powered applications with heat loads exceeding 200W.

Quick Selection Rules for Design Reviews

Use these logic gates during your initial system architecture review:

- Rule 1: If the target internal temperature is below the maximum ambient temperature, you typically need active compressor-based cooling.

- Rule 2: If the enclosure must remain sealed (NEMA 4/4X or IP65 targets) to block salt spray or conductive dust, open-loop airflow is usually disqualified.

- Rule 3: If the power budget is tight (solar/battery), compare the COP. Vapor compression systems generally move more watts of heat per watt of input power than Peltier plates.

- Rule 4: If the heat load exceeds 300W–400W, thermoelectric coolers often become impractical due to excessive power draw and heatsink size.

- Rule 5: If maintenance intervals exceed 6 months, avoid solutions that rely on filter media, as clogging leads to rapid thermal derating.

Failure Modes: The Unseen Enemies of Uptime

Validation is essentially the process of hunting for failure modes before they manifest in the field. In the context of sealed cabinet cooling, failures are rarely catastrophic explosions; they are slow, creeping degradations. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for designing a robust test plan.

1. The Filter Clogging Fallacy

In open-loop systems or poorly designed closed-loop systems with external condenser filters, dust is the primary enemy. As filter media loads with particulate matter, static pressure increases and airflow drops. This reduces the heat rejection capability of the condenser. In a micro DC air conditioner validation test, engineers often test with clean filters, failing to account for the 50% airflow reduction that might occur after six months in a dusty mine or agricultural setting.

Result: High-pressure trips or reduced cooling capacity leading to internal hotspots.

2. Short-Cycling and Thermal Runaway

If the cooling unit is oversized or the hysteresis (the gap between turn-on and turn-off temperatures) is too tight, the compressor may cycle on and off rapidly. This places immense stress on the driver board and motor windings. Conversely, if the unit is undersized, it runs continuously without ever reaching the setpoint, eventually draining the battery in off-grid scenarios.

Result: Premature component fatigue or battery depletion.

3. Condensate Mismanagement

Active cooling dehumidifies the air inside the cabinet. In a perfectly sealed enclosure, moisture is limited to what was trapped during closing. However, if the seal is imperfect (which is common), moisture continuously enters and condenses on the evaporator coil. If the condensate drain is clogged, kinked, or routed incorrectly, water can back up into the electronics.

Result: Short circuits and corrosion on the very PCBs the AC was meant to protect.

4. Inrush Current Trips

DC compressors, particularly older designs, can draw significant current during startup (locked rotor amps). If the power supply or battery management system (BMS) detects this spike as a short circuit, it may cut power. Modern BLDC inverter compressors typically feature soft-start logic to mitigate this, but it remains a critical parameter to measure.

Result: System fails to start, despite having sufficient steady-state power capacity.

Engineering Fundamentals: Plain Language Physics

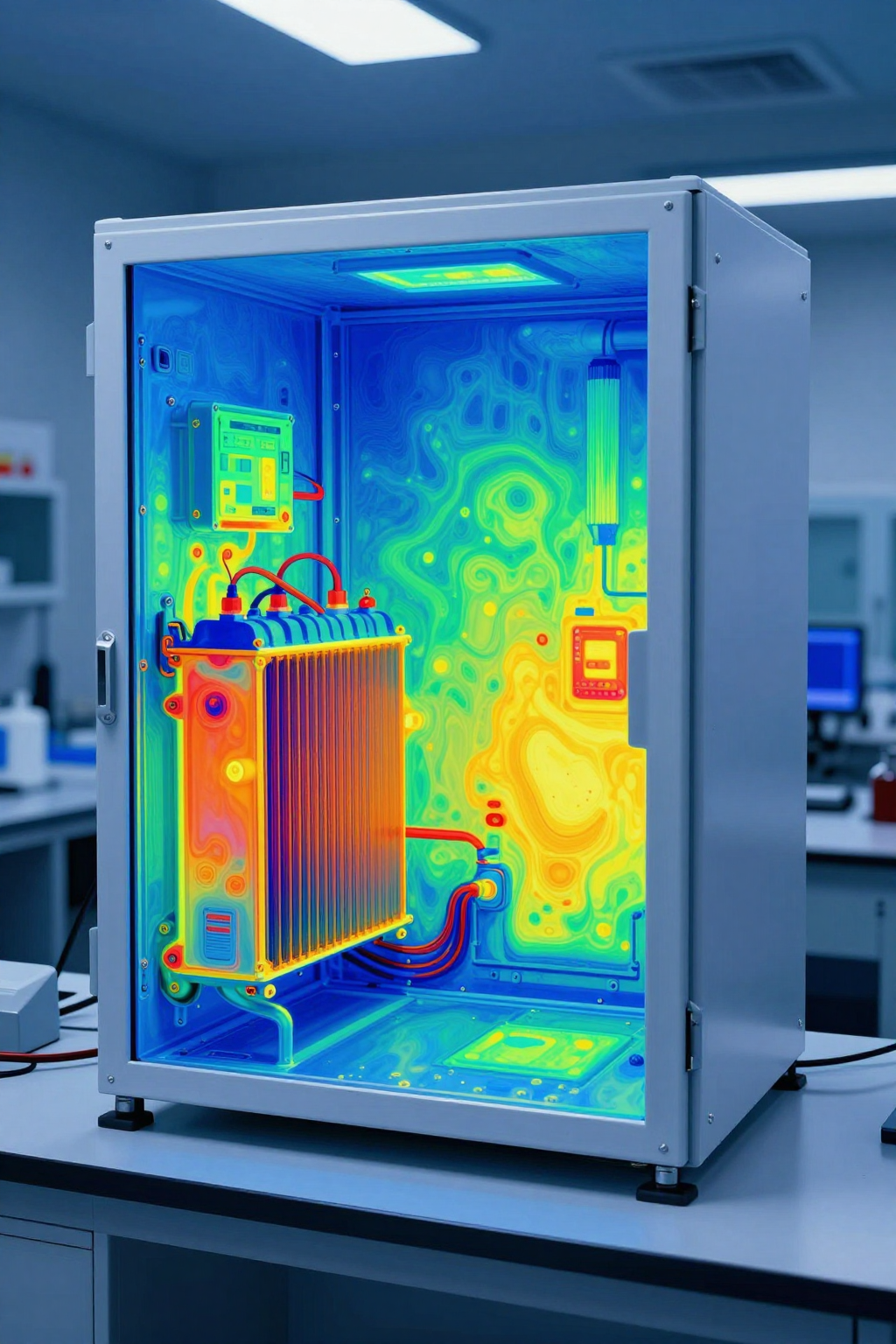

To validate a Micro DC Aircon effectively, one must understand the underlying thermodynamics. Unlike a fan that simply facilitates heat exchange, a vapor-compression cycle actively pumps heat against the thermal gradient.

The Delta T Burden

Delta T refers to the temperature difference between the condenser air (outside) and the evaporator air (inside). The harder the system has to work to push heat into a hot ambient environment, the higher the pressure ratios in the compressor. This increases power consumption and reduces cooling capacity. Validation tests must simulate the “worst-case Delta T”—typically the hottest expected day with the highest internal heat load.

Inverter Technology (BLDC)

The Micro DC Aircon utilizes a Brushless DC (BLDC) rotary compressor. Unlike fixed-speed AC compressors that are either fully on or fully off, BLDC motors can modulate their speed (RPM) based on the thermal load. This variable speed operation improves efficiency and temperature stability. However, it also introduces complexity in validation; you must verify that the controller correctly ramps up RPM under heavy load and ramps down when the setpoint is approached.

Sealing Reality

Closed-loop designs avoid air exchange, but overall ingress protection still depends on gasket integrity, cable glands, and installation quality. A cooling unit cannot compensate for a cabinet that leaks hot, humid air faster than the evaporator can cool it. Validation must include a “leak down” or pressurization test of the integrated cabinet.

Performance Data & Verified Specs

When selecting a unit for validation, rely on verified specifications rather than estimates. The following table outlines parameters for the Arctic-tek Micro DC Aircon series, specifically the DV models which are frequently used in these applications.

| Model | Voltage (DC) | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant | Compressor Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC (Pro) | 12V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 550W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

Note: Cooling capacity varies based on ambient temperature and internal setpoint. The values above represent nominal conditions. Always consult the specific performance curves for your operating range.

These units integrate the compressor, condenser, evaporator, and driver board into a compact module. The availability of 12V, 24V, and 48V options allows for direct connection to battery banks or DC buses without the efficiency loss of an inverter (DC to AC).

Field Implementation Checklist: The Validation Protocol

A robust micro DC air conditioner validation test should be conducted on the fully integrated system, not just the cooling unit in isolation. Use this checklist to structure your test plan.

1. Mechanical Integration & Sealing

- Gasket Compression: Verify that the mounting flange gasket is compressed uniformly. Uneven torque on mounting bolts can create gaps.

- Airflow Management: Ensure there is no “short-circuiting” of airflow. The cold air discharge should not be immediately sucked back into the return intake. Use baffles or ducting if necessary to force air through the heat-generating components.

- Condensate Routing: Pour water into the evaporator tray (if accessible) or run the unit in high humidity to verify that the drain line flows freely and exits the cabinet without leaking internally.

2. Electrical & Power Profiling

- Voltage Drop Test: Measure voltage at the compressor terminals during startup. Long cable runs or undersized wiring can cause voltage drops that trigger under-voltage protection, even if the battery is full.

- Current Draw Logging: Log current consumption over a full 24-hour cycle. Verify that the average power draw aligns with your energy budget.

- Fuse Sizing: Ensure the fuse or breaker is sized to handle the startup current transient without nuisance tripping.

3. Thermal Stress Testing

- Solar Load Simulation: If a climate chamber is unavailable, use heat lamps to simulate solar loading on the cabinet walls while the unit is running.

- Max Ambient Test: Operate the system at the maximum rated ambient temperature (e.g., using a hot box or temporary enclosure) and verify that the internal temperature remains below the critical threshold for your electronics.

- Recovery Time: Open the cabinet door for 5 minutes to let heat in, then close it and measure how long the system takes to return to the setpoint. This indicates reserve capacity.

4. Maintenance & Reliability

- Filter Access: If an external filter is used, verify it can be changed without tools.

- Vibration Check: Ensure that refrigerant lines are not rubbing against the chassis, which could lead to leaks over time.

Expert Field FAQ

Q: How does the Micro DC Aircon handle voltage fluctuations in mobile applications?

A: The integrated driver board typically monitors input voltage. If the voltage drops below a safety threshold (e.g., to protect a vehicle battery from deep discharge), the unit will shut down. It usually attempts to restart automatically once the voltage recovers. This behavior should be verified during your micro DC air conditioner validation test.

Q: Can I mount the unit in any orientation?

A: Generally, no. Vapor compression systems rely on oil circulation for lubrication. Most rotary compressors must be mounted upright (within a specific angle, often < 30 degrees) to ensure oil returns to the sump. Consult the specific model’s installation guide.

Q: What is the impact of altitude on cooling capacity?

A: Air density decreases with altitude, which reduces the mass flow rate of air over the heat exchangers. This typically results in a derating of cooling capacity. If deploying at high elevations (e.g., > 2000m), you may need to oversize the unit slightly.

Q: Do I need a separate heater for cold nights?

A: The Micro DC Aircon is primarily for cooling. If your electronics have a minimum operating temperature and the environment gets extremely cold, a separate resistive heater is often required. Some system integrators use the waste heat from the electronics themselves to maintain temperature, only engaging the AC when the cabinet gets too hot.

Q: How do I determine the correct cooling capacity?

A: You must calculate the total heat load: Internal Heat Dissipation (Watts) + Solar Load (Watts) + Heat Transfer through walls (Watts). The cooling unit’s capacity at the expected ambient temperature must exceed this total. We recommend a safety margin of 20–30%.

Q: What happens if the condensate drain freezes?

A: In standard operation, the evaporator should not freeze if airflow is sufficient. However, if the internal temperature is set very low or airflow is blocked, ice can form. Most controllers have freeze protection sensors, but a heated drain line may be necessary in specific sub-freezing ambient conditions where the condensate could freeze at the exit point.

Conclusion & System Logic

Validating a sealed enclosure cooling system is about more than ensuring the compressor turns on. It is about verifying that the thermal loop—comprising the DC condensing unit, the cabinet insulation, the airflow path, and the power supply—functions as a cohesive system under stress. The “set it and forget it” mentality is a recipe for field failure.

By following a structured micro DC air conditioner validation test plan, engineers can expose weaknesses in sealing, power delivery, and thermal headroom before the equipment leaves the factory. Whether you are cooling a 12V mobile medical bay or a 48V desert telecom site, the physics remain constant: heat must be moved efficiently, reliably, and without compromising the enclosure’s protective seal.

The Micro DC Aircon series provides the thermal muscle for these challenges, but it is the quality of the integration and validation that ensures long-term uptime. Treat the validation phase not as a hurdle, but as the final design review.

Request Sizing & Integration Support

If you are in the design phase and need to verify your thermal calculations or select the appropriate Micro DC Aircon model, our engineering team can assist. To expedite the process, please prepare the following inputs:

- Target Internal Temperature: (e.g., 25°C, 35°C)

- Maximum Ambient Temperature: (e.g., 50°C, 60°C)

- Internal Heat Load: Estimated dissipation of components in Watts.

- Power Source: Voltage (12V/24V/48V) and current limits.

- Cabinet Dimensions & Insulation: To estimate solar and conductive loads.

- Sealing Requirement: IP rating or NEMA type.

0 条评论