Angle Lock: The decision is whether to specify a native DC air conditioner or use an existing DC-to-AC inverter to power a conventional AC cooling unit. The primary failure modes are inverter failure under thermal load and catastrophic battery drain from compounded power conversion losses. The dominant constraint is total system power efficiency in a native DC power architecture.

Direct DC Cooling vs Inverter: A Total System Efficiency Breakdown

For engineers designing systems around a native DC power architecture—be it a 48V telecom shelter, a 24V autonomous vehicle, or a 12V off-grid installation—every component choice is a referendum on system reliability and power budget. One of the most critical decisions is thermal management. The default path is often to leverage a large DC-to-AC inverter to power commodity AC equipment, including air conditioners. This approach, while seemingly straightforward, introduces hidden inefficiencies and failure points that can compromise the entire system. The choice between a direct DC cooling vs inverter-based AC solution is not just about the cooling unit; it’s about the integrity of your power architecture.

A failure in the cooling subsystem doesn’t just mean things get warm; it means critical electronics derate, performance degrades, and catastrophic failure becomes imminent. By the end of this analysis, you will be able to confidently evaluate the system-level tradeoffs and justify the selection of a native DC air conditioner over an AC unit paired with an inverter. In this article, we prioritize total system watt-for-watt efficiency and reliability over the upfront component cost of the cooling unit itself, because in DC power architectures, every conversion loss is a system-level liability.

Deployment Context: Where the Power Path Matters

Theoretical efficiency numbers mean little without real-world context. The engineering debate over using a DC air conditioner vs an AC inverter setup comes into sharp focus in environments where power and reliability are paramount.

Scenario A: The Remote 48VDC Telecom Shelter

A network operator deployed a remote cell site running on a 48V DC power plant with battery backup. To cool the sensitive radio and backhaul equipment, they installed a standard commercial AC air conditioner powered by a large, rack-mounted DC-to-AC inverter. During a regional heatwave, the shelter’s internal temperature soared. The inverter, already operating at high capacity and in a hot environment, began to derate its output to protect itself. This caused the AC unit to cycle improperly, and eventually, the inverter faulted and shut down, leading to a total loss of cooling. The resulting network outage required an expensive emergency dispatch. The root cause was not the air conditioner itself, but the introduction of a thermally sensitive, inefficient conversion step as a critical single point of failure.

Scenario B: The 24VDC Autonomous Mobile Robot

An engineering team developing an autonomous logistics robot with a 24V DC lithium battery system needed to actively cool its high-power compute and sensor suite. Their initial design used a compact, off-the-shelf DC-to-AC inverter to run a small AC appliance cooler. During endurance testing, they found the robot’s operational range was 20% less than projected. Analysis revealed that the power conversion from 24V DC to 110V AC, followed by the AC cooler’s own internal conversion back to low-voltage DC for its electronics, was wasting a significant portion of the battery’s charge. This “power conversion tax” created a parasitic load that directly reduced mission duration and increased the total cost of ownership through more frequent charging cycles.

Failure Modes & System Constraints, Ranked

When integrating an AC cooling unit into a DC environment via an inverter, the potential issues extend far beyond simple inefficiency. The entire system becomes more fragile. Here are the most common failure modes, ranked by their potential impact on system-level reliability.

- Inverter Failure → Total Cooling Loss → The inverter is a complex electronic device that becomes a single point of failure; its failure under thermal or electrical stress guarantees a cooling shutdown.

- Compounded Efficiency Loss → Accelerated Battery Drain → A DC-to-AC inverter (85-95% efficient) followed by the AC unit’s internal AC-to-DC power supply (90-95% efficient) can waste 10-25% of your power budget before the compressor even starts.

- Increased Thermal Load → Enclosure Heat Rise → The energy lost during DC-to-AC conversion becomes heat, which is often dissipated by the inverter *inside* the very enclosure you are trying to cool, adding to the total thermal burden.

- Higher Standby Power Draw → Constant Parasitic Load → Inverters consume power (tare loss) just by being on, even when the AC compressor is cycled off, creating a persistent drain on the battery bus.

- System Complexity → Higher Mean Time To Repair (MTTR) → The addition of the inverter, its dedicated wiring, and AC-side circuit protection means more components to fail and a more complex system to troubleshoot in the field.

- Voltage Sag on Startup → DC Bus Instability → The high inrush current required to start an AC compressor can cause a momentary sag on the DC bus, potentially disrupting or resetting sensitive electronics sharing the same power source.

- Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) → Signal Integrity Risk → The switching electronics within power inverters can generate significant EMI, which may interfere with sensitive RF communications or sensor equipment in the enclosure.

Engineering Fundamentals: The Power Conversion Tax

The core of the direct dc cooling vs inverter argument lies in understanding the “Power Conversion Tax.” Every time electricity is converted from one form to another (e.g., DC to AC, or high voltage to low voltage), a percentage of that energy is irrevocably lost as waste heat. A system built on a native DC architecture is inherently efficient because it minimizes these conversion steps.

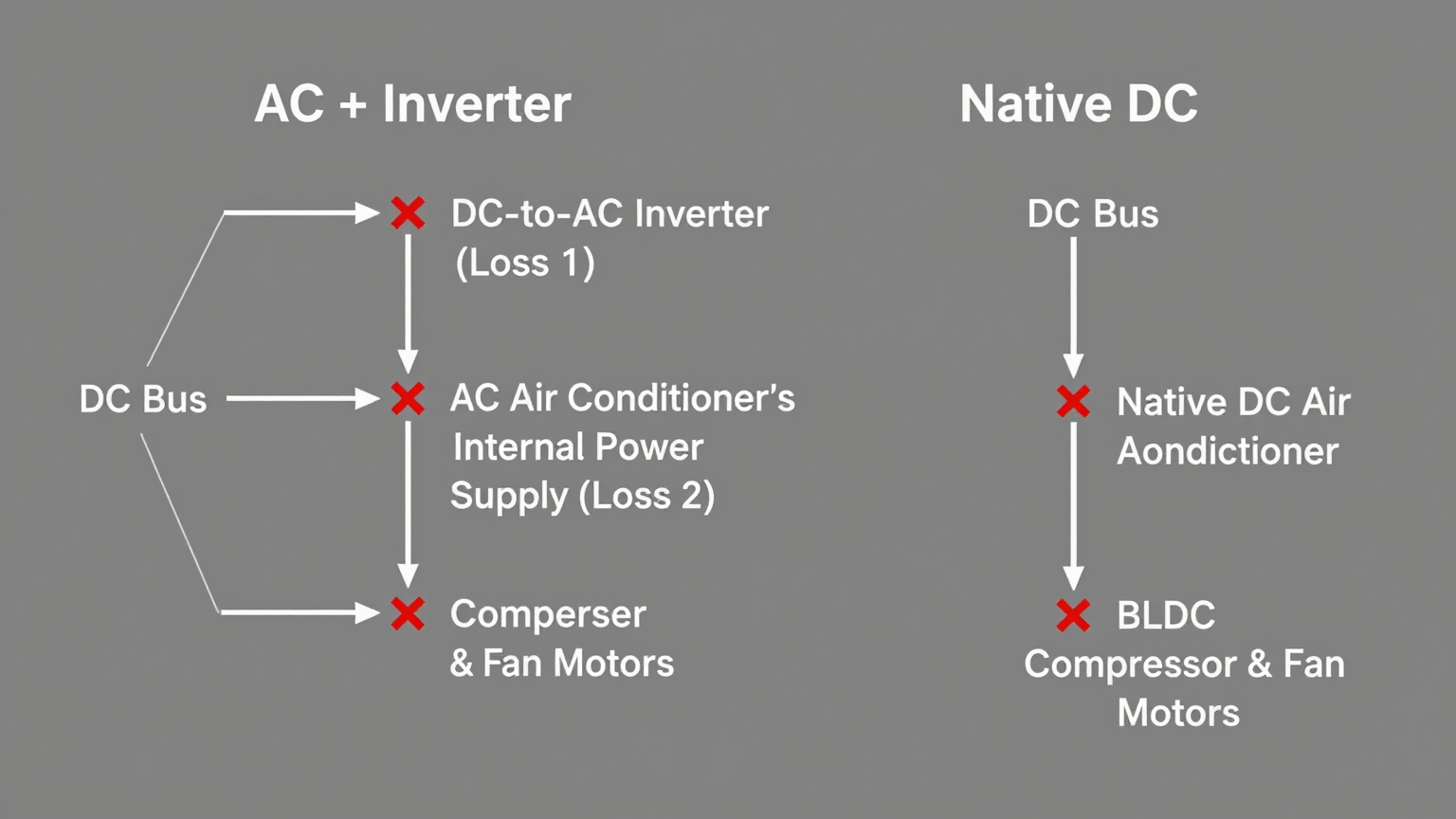

When you introduce a DC-to-AC inverter to run an AC air conditioner, you create a convoluted and lossy power path:

- Path 1 (AC + Inverter): DC Bus → DC-to-AC Inverter (Loss #1) → AC Power → AC Air Conditioner’s Internal Power Supply (converts AC back to DC for logic/fans – Loss #2) → Compressor & Fan Motors.

- Path 2 (Native DC): DC Bus → Native DC Air Conditioner (direct to BLDC Compressor & Fan Motors).

The native DC air conditioner follows the second path, directly utilizing the DC power to run its high-efficiency, variable-speed brushless DC (BLDC) compressor and fans. This eliminates the two major conversion losses entirely, meaning more of your stored battery power goes directly to creating cold air.

Common Misconception: “A modern, high-efficiency inverter rated at 95% makes the conversion loss negligible.”

Engineering Correction: That 5% loss is only the first part of the tax. It doesn’t account for the inverter’s own standby power draw, nor the additional 5-10% loss from the AC appliance’s own internal power supply that must convert the power *back* to DC for its control board and fan motors. Furthermore, that initial 5% loss manifests as heat, often inside the cabinet, which the cooling system must then work even harder to remove. The losses are compounded, and they directly impact both your power budget and your thermal load.

Key Specifications for Direct DC Cooling Solutions

When evaluating a native DC cooling unit, the specifications shift from AC power characteristics to direct alignment with your DC bus. The goal is to match the unit to your existing architecture to eliminate conversions. Here are the critical parameters for a solution like the Micro DC Aircon series.

| Model (Example) | Input Voltage (VDC) | Nominal Cooling Capacity (W) | Refrigerant |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 450W | R134a |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 550W | R134a |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V | 450W | R134a |

When analyzing the DC air conditioner vs AC inverter choice, the first spec to check is the Input Voltage. It must natively match your system’s power bus (e.g., 12V, 24V, 48V) to render an external inverter obsolete. The Nominal Cooling Capacity provides the baseline cooling power, which must then be carefully sized for your specific internal heat load, maximum ambient temperatures, and desired internal temperature delta. This direct approach simplifies system design and maximizes performance.

Engineering Selection Matrix: Logic Gates for Integration

An engineer’s decision process is a series of logic gates. Here’s how to apply that thinking to the direct DC cooling vs inverter question.

Logic Gate 1: The Power Architecture Gate

- Constraint Gate: The system is built on a native DC power bus (e.g., 12V, 24V, or 48VDC).

- Decision Trigger: If the primary power source is DC and overall system power efficiency is a key performance indicator.

- Engineering Resolution: Prioritize a native direct DC cooling solution. Actively avoid introducing a DC-to-AC conversion step and its associated failure modes and inefficiencies solely for thermal management.

- Integration Trade-off: This requires sourcing a specialized DC-native component instead of a commodity AC unit. However, it simplifies the Bill of Materials (BOM) by eliminating the inverter, AC-side wiring, and associated protection devices, while increasing total system reliability.

Logic Gate 2: The Endurance and TCO Gate

- Constraint Gate: The application is power-constrained by a battery bank or an off-grid source like solar.

- Decision Trigger: If the system must operate for a maximum duration on a single charge or within a limited daily power generation budget.

- Engineering Resolution: Select a variable-speed native DC air conditioner. The 10-25% power savings from eliminating conversion losses directly translates to longer operational endurance or allows for a smaller, lighter, and less expensive battery and power generation infrastructure.

- Integration Trade-off: The upfront capital expenditure for the specialized DC unit may be higher than a cheap AC appliance. However, the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is significantly lower due to reduced energy consumption and the potential for downsizing the entire power system.

Logic Gate 3: The Reliability and Serviceability Gate

- Constraint Gate: The system requires high availability (e.g., 99.999% uptime) or is deployed in a remote, difficult-to-service location.

- Decision Trigger: If system downtime leads to significant revenue loss, mission failure, safety risks, or requires costly field service dispatches.

- Engineering Resolution: Choose the architecture with the fewest failure points. The comparison of a DC air conditioner vs an AC inverter system is clear: removing the inverter from the power path eliminates a major source of thermal and electrical failure, directly increasing the system’s Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF).

- Integration Trade-off: Field technicians may be less familiar with integrated DC cooling units compared to standard AC window units. This may necessitate providing specific documentation or training for maintenance procedures.

Implementation Checklist for Direct DC Cooling

Proper integration is key to realizing the benefits of a native DC cooling solution. Follow this checklist to ensure a robust and reliable installation.

- Mechanical Integration

- Mounting: Securely fasten the unit to the enclosure, using vibration dampeners if required by the application. Ensure the mounting orientation complies with the manufacturer’s guidelines for condensate management.

- Sealing: Use the provided gaskets and ensure all sealing surfaces are clean and properly compressed to maintain the enclosure’s environmental rating (e.g., NEMA or IP).

- Airflow Integrity: Verify that the internal (cold) and external (hot) air paths are completely separated to maintain a closed-loop system and prevent efficiency loss.

- Electrical Integration

- Power Cabling: Use the appropriate wire gauge for the specified DC current draw and cable length to minimize voltage drop.

- Circuit Protection: Install a correctly rated DC fuse or circuit breaker on the positive line as close to the power source as possible.

- Control Wiring: Connect thermostat or control signals according to the wiring diagram. Ensure control wires are shielded and routed away from high-power cables if EMI is a concern.

- Thermal Validation

- Sensor Placement: Position the temperature sensor in a location that reflects the average air temperature around the critical components, not in the direct cold air stream from the unit.

- Acceptance Testing: Once installed, operate the system under full thermal load on a warm day. Use a data logger or thermal camera to confirm that the internal temperature is maintained at or below the target setpoint.

- Maintenance Planning

- Access: Ensure the unit is installed in a way that allows for easy access to the condenser coils and fans for periodic cleaning.

- Inspection Schedule: For units in dusty or dirty environments, establish a regular schedule to inspect and clean condenser coils to prevent airflow blockage, which is a primary cause of performance degradation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is an AC unit with a high-efficiency inverter just as good?

No. Even a 95% efficient inverter wastes 5% of power as heat and still requires the AC unit’s internal power supply to perform a second, lossy conversion. A native DC solution bypasses both conversion steps, making it fundamentally more efficient at the system level.

2. What if my electronics enclosure needs to be fully sealed (e.g., IP67)?

This is an ideal scenario for a closed-loop Micro DC Aircon. These units mount through the wall of the enclosure, using separate internal and external fans to transfer heat out without mixing air, thereby preserving the seal and protecting internal electronics from dust and moisture.

3. How is condensation managed in a direct DC cooling system?

Condensation is managed identically to any vapor-compression air conditioning system. Well-designed units have integrated condensate collection and drainage ports. Proper mounting and ensuring the drain path is clear are critical for any AC or DC system.

4. How does direct sun exposure affect the choice between direct DC cooling vs inverter AC?

Direct solar load significantly increases the total heat that must be removed from an enclosure. This affects the *sizing* of the cooling unit required, but it makes the efficiency of the chosen solution even more critical. In a power-limited scenario, the superior efficiency of a direct DC system becomes a massive advantage as the cooling demand rises.

5. What are the top 3 things I must measure before selecting any cooling unit?

1) The total internal heat load from your electronics (in watts). 2) The maximum expected ambient temperature outside the enclosure. 3) The target maximum allowable temperature inside the enclosure. These three values determine the required cooling capacity.

6. How can I validate the cooling performance after installation?

The best method is data logging. Place thermocouples near your most sensitive components and log the internal enclosure temperature while the system is running under its maximum real-world load. Compare this data against the ambient temperature to confirm the system is maintaining the required temperature differential.

7. What is the core component difference between a DC air conditioner vs an AC inverter model?

The motors. A true native DC air conditioner uses a brushless DC (BLDC) compressor and BLDC fan motors that run efficiently and directly from the DC power source. An AC unit uses motors designed for AC power, necessitating the power conversion steps that a native DC system is designed to eliminate.

Conclusion: The Architecturally Superior Choice

The debate over direct DC cooling vs inverter-powered AC solutions is ultimately a question of system-level engineering philosophy. While using an inverter to power a commodity AC unit may seem like a convenient shortcut, it introduces unacceptable compromises in efficiency, reliability, and complexity for any serious DC power application. The compounded power losses, added heat load, and introduction of a critical single point of failure are significant design liabilities.

For any system built upon a native 12V, 24V, or 48V DC architecture, a direct DC air conditioner is the architecturally superior choice. It aligns with the core principles of the power system, maximizing efficiency by eliminating wasteful conversions and enhancing reliability by simplifying the overall design. This approach ensures that your power budget is spent on cooling your critical electronics, not on feeding parasitic loads.

If you are designing a thermal management solution for a DC-powered system, our engineering team can assist with thermal load calculations and help specify a direct DC cooling unit that integrates seamlessly with your power constraints, enclosure geometry, and environmental challenges. Contact us for a design consultation to explore the right fit for your project.

0 条评论