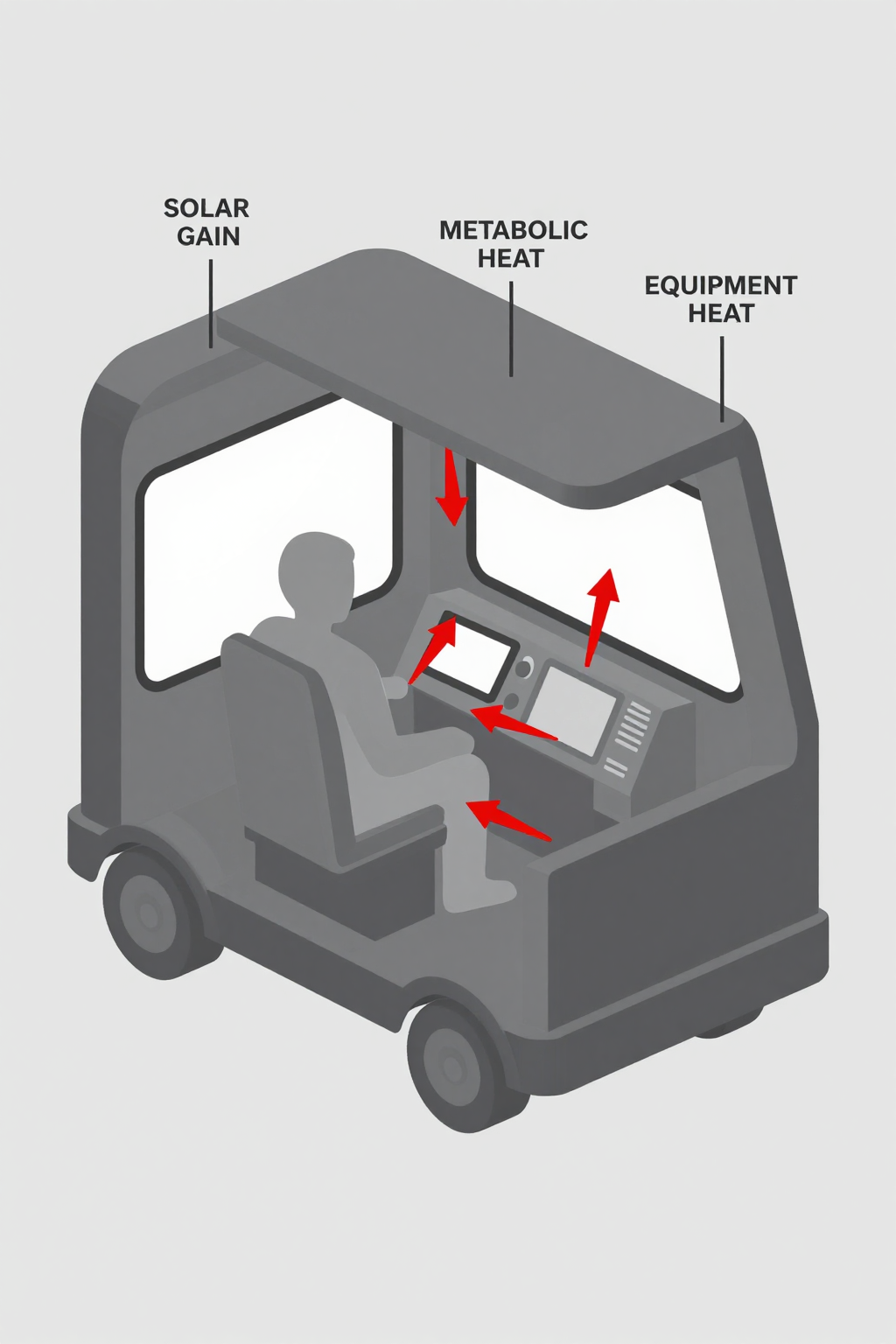

A recent field consult involved a fleet of mining haul trucks where operators were experiencing significant heat stress despite the cabin’s conventional air conditioning. During long, 10-hour shifts under direct sun, the combination of high ambient temperatures, solar load through the large cabin windows, and the operator’s own metabolic heat was overwhelming the existing HVAC system. The core problem wasn’t just warm air; it was direct, personal thermal load. This situation created a clear need for a solution that could directly manage the operator’s microclimate without overburdening the vehicle’s limited power and space.

This post documents the decision-making process we followed, moving from initial checks to the engineering trade-offs that pointed toward an active, liquid-based cooling solution. By the end of these notes, you’ll be able to identify the key constraints that make an active industrial operator cooling suit system a practical and often necessary choice over passive or up-rated ambient cooling methods.

Field Snapshot: Evaluating an Industrial Operator Cooling Suit System

The scenario was a familiar one: a heavy industrial environment with non-negotiable operational demands. The operators were in enclosed cabins, but the thermal challenge was multifaceted. Simply lowering the cabin air temperature further was proving ineffective and inefficient. The goal was to reduce the risk of heat-related illness and improve operator alertness over the full shift duration. We needed a solution that was robust, sustainable for long hours, and integrated cleanly with the existing vehicle platform. This is where a systematic evaluation of the thermal load and system constraints becomes critical.

First Engineering Checks on Site

Before considering new hardware, we always start with a baseline assessment of the existing setup. These initial checks help define the problem’s boundaries and prevent investment in a solution that doesn’t address the root cause.

- Check: Cabin Air Temperature vs. Operator’s Reported Discomfort.

Why: We needed to confirm if the issue was ambient heat or direct thermal load. The cabin AC could hold 22°C, but operators still reported overheating.

What it suggests: The problem was likely radiant heat from the sun and metabolic heat buildup, which standard air conditioning struggles to mitigate effectively. Cooling the person, not just the air, is a more direct approach. - Check: Available DC Power Budget.

Why: Any active system requires power. We assessed the vehicle’s 24VDC electrical system, including the alternator’s total capacity and the load from other essential systems.

What it suggests: There was a limited power budget. Any potential solution needed a low power draw, likely ruling out power-intensive options like larger, conventional HVAC units. A system with a peak draw around 240W was deemed feasible. - Check: Existing HVAC Duty Cycle.

Why: We monitored the existing air conditioner’s compressor to see how often it was running. It was at a near-100% duty cycle throughout the peak temperature hours.

What it suggests: The current system was already at its maximum capacity. Simply servicing it wouldn’t provide the necessary additional cooling. A supplementary or alternative cooling strategy was required.

Common Failure Modes & Constraints of Alternative Cooling

Several alternative solutions are often proposed in these scenarios. However, they each come with constraints that, in this case, made them unsuitable for long-duration, high-heat industrial applications. Understanding these failure modes is key to specifying a reliable system.

- Symptom: Rapidly diminishing cooling effect after 1-2 hours.

Likely Cause: Ice-pack or phase-change material vests are exhausted.

Why it matters: For an 8 to 12-hour shift, this approach is operationally impractical. It requires operators to carry multiple sets of inserts and find freezer space, adding logistical complexity and creating inconsistent cooling. - Symptom: Excessive, high-pitched noise in the cabin (>85 dBA).

Likely Cause: Vortex tube cooling vests running on compressed air.

Why it matters: Besides the potential for hearing damage over a long shift, these systems place a significant and inefficient load on the vehicle’s compressed air system, which is often needed for other critical functions like brakes and suspension. - Symptom: High power consumption with minimal perceived cooling.

Likely Cause: Peltier device (thermoelectric) based cooling systems.

Why it matters: While solid-state, Peltier modules are notoriously inefficient, especially in high ambient temperatures. They would quickly overwhelm the vehicle’s limited DC power budget for the amount of heat they can realistically move. - Symptom: Operator remains overheated despite a cold cabin.

Likely Cause: An upgraded, more powerful cabin HVAC system was installed.

Why it matters: This approach still fails to address direct solar gain on the operator’s body. It cools the air, but the operator continues to absorb radiant heat, leading to a situation where the ambient environment is uncomfortably cold while the person is still hot.

Decision Gates for Active Liquid Cooling

Based on the initial checks and the limitations of alternatives, we established four clear decision gates. If the operational requirements meet the trigger for each gate, an active liquid-cooled industrial operator cooling suit system becomes the most logical engineering path.

Gate 1: The Shift Duration Constraint

- Constraint: Continuous operation is required for shifts longer than three hours.

- Decision Trigger: Passive cooling methods like ice vests cannot provide consistent cooling for the entire duration.

- Engineering Resolution: Implement an active cooling system with a continuous duty cycle, powered by the vehicle. A miniature vapor-compression system circulates cooled liquid through a garment, providing stable performance as long as power is available.

- Integration Trade-off: The system is no longer “wear and forget.” It requires a physical connection (umbilical) to a power and cooling unit, which must be managed by the operator upon entering and exiting the cabin.

Gate 2: The Power Budget Constraint

- Constraint: The solution must run on a standard 24VDC vehicle electrical system without compromising other onboard systems.

- Decision Trigger: The available power budget cannot support inefficient or high-draw solutions.

- Engineering Resolution: Select a system optimized for DC power. The AlphaCooler unit, with its 240W peak power draw, is designed specifically for this constraint, offering a high coefficient of performance compared to thermoelectric alternatives.

- Integration Trade-off: The system’s total cooling capacity is directly tied to its power draw. While the 500W of cooling capacity is substantial for personal cooling, it is not designed to cool the entire cabin.

Gate 3: The Thermal Load Constraint

- Constraint: High ambient temperatures (above 35°C) are combined with significant solar gain through glass.

- Decision Trigger: Ambient air cooling is insufficient to overcome the direct radiant heat load on the operator.

- Engineering Resolution: Deploy a direct-to-body cooling solution. A liquid-cooled garment removes heat directly from the skin, intercepting metabolic and environmental heat before it can elevate core body temperature. This is far more efficient than over-cooling the surrounding air.

- Integration Trade-off: Requires the operator to wear a specialized garment. Fit and comfort become important factors for user acceptance.

Gate 4: The Space and Weight Constraint

- Constraint: The hardware must fit within the tight confines of an existing operator cabin without obstructing movement or visibility.

- Decision Trigger: There is no physical space to install a larger, conventional air conditioning unit.

- Engineering Resolution: Utilize a compact, self-contained cooling unit. A unit with a small footprint (e.g., 295 x 195 x 170 mm) and low weight (5.2 kg) can often be mounted behind a seat or in an unused compartment.

- Integration Trade-off: Placement is critical. The unit’s heat exchanger requires a minimum amount of clear space for airflow, and its location must be chosen to minimize vibration and facilitate maintenance access.

Integration Notes for System Integrators

Deploying an industrial operator cooling suit system is not just about mounting a box. Careful integration is essential for performance and reliability. These are not step-by-step instructions but rather a summary of key considerations from our field experience.

- Mechanical: The cooling unit is designed for high-vibration environments, but proper mounting is crucial. Use all specified M5 mounting points and consider adding vibration-damping grommets. Plan a clear and secure route for the liquid umbilical to prevent snagging or kinking during normal operator movement.

- Electrical: Connect directly to a fused 24VDC source. Ensure the wiring gauge is sufficient to handle the 240W peak load without significant voltage drop. Avoid sharing circuits with sensitive electronics where possible.

- Thermal: The unit is an air-cooled condenser. It inhales ambient cabin air and exhausts warm air. Do not install it in a sealed compartment. Ensure the air intake and exhaust vents are unobstructed to maintain cooling efficiency. Use the recommended coolant mixture (distilled water and glycol) to prevent freezing or biological growth.

- Maintenance: The system is largely self-contained. The primary maintenance tasks involve periodically checking the coolant level in the reservoir and ensuring the condenser fins are clean and free of dust or debris that could impede airflow.

Frequently Asked Questions from the Field

Why not just install a more powerful cabin air conditioner?

A bigger AC unit still struggles with direct solar radiation on the operator and is less energy-efficient. Direct-to-body cooling targets the heat load at its source, providing greater comfort with a much lower power draw compared to brute-force cabin cooling.

Is the 240W power draw a concern for our vehicle’s alternator?

This power level is typically well within the capacity of heavy vehicle electrical systems. However, a full power budget analysis is always recommended to ensure the total electrical load from all systems remains within the alternator’s sustained output capacity.

How durable are the cooling garment and the umbilical connection?

These components are designed for industrial environments. The umbilical uses robust, quick-disconnect fittings. However, like any equipment, proper use and care are important. Training operators on how to route and manage the umbilical prevents unnecessary strain on the connectors.

What is the actual cooling capacity we can expect?

The system is rated to remove up to 500 watts of heat. This is typically sufficient to manage the combined metabolic heat load of a person under moderate strain and a significant amount of environmental heat gain, creating a comfortable microclimate even in a hot cabin.

How does the system perform under constant, heavy vibration?

The vapor-compression system is engineered for mobile applications. Its reliability is heavily dependent on the quality of the mechanical installation. Secure mounting with appropriate vibration damping is the key to long-term performance in mining or heavy construction equipment.

What is the maintenance schedule for a unit deployed in a dusty environment?

In dusty conditions, the primary maintenance item is the condenser coil. A monthly visual inspection and cleaning with compressed air are often sufficient to ensure proper airflow and thermal performance.

Conclusion: When Active Cooling is the Right Call

For industrial applications like mining, crane operations, or agriculture, an active industrial operator cooling suit system is a highly effective solution when specific constraints are met. If operators are working long shifts in high-heat environments with significant solar load, and the vehicle has tight power and space limitations, direct-to-body liquid cooling moves from a luxury to a critical piece of safety and performance equipment.

This approach is not a universal replacement for traditional HVAC. But when conventional methods fail to protect operators from heat stress, a targeted microclimate system provides a robust, efficient, and reliable alternative. For detailed specifications on microclimate cooling units designed for these environments, see the AlphaCooler series.

0 条评论