Engineering Reliability: Selecting a Micro AC for Remote Outdoor Cabinet Deployments

For operations engineers and system integrators managing distributed infrastructure, the “truck roll” is often the single most expensive line item in the maintenance budget. When a remote site goes dark, the cost is rarely just the replacement hardware; it is the travel time, the specialized technician rates, the vehicle wear, and the opportunity cost of downtime. In the context of unattended sites—whether desert telecom repeaters, coastal environmental sensors, or roadside traffic control systems—thermal management is frequently the hidden variable that dictates site reliability.

The challenge is distinct from data center cooling. There is no raised floor, no constant utility power, and often no human presence for months. The enclosure must fight a hostile environment where ambient temperatures may exceed the safe operating limits of the internal electronics, and where opening the door to “let it breathe” invites dust, salt fog, and humidity. This article explores the engineering logic behind selecting a micro ac for remote outdoor cabinet applications, focusing on the trade-offs between passive venting, thermoelectric cooling, and vapor-compression systems.

Our goal is to provide a defensible framework for technical buyers. We will strip away marketing superlatives and focus on the physics of heat rejection, the realities of power budgets, and the practical constraints of sealing. By the end of this guide, you should have the inputs necessary to size a solution that balances thermal performance with the operational imperative to reduce site visits.

Deployment Context: The Hostile Reality of the Edge

To understand the cooling requirements, we must first characterize the thermal load and environmental aggression typical of remote deployments. Unlike a climate-controlled server room, an outdoor cabinet is subject to solar loading that can double the effective heat load on the internal components. We typically see two distinct scenarios driving the need for active, closed-loop cooling.

Scenario A: The Solar-Powered Desert Repeater

Consider a telecommunications repeater station located off-grid in an arid region. The ambient air temperature often peaks between 45°C and 55°C during the day. The internal electronics—power amplifiers, routers, and battery management systems—have a maximum safe operating temperature of roughly the same range. This creates a zero or negative temperature headroom scenario. Passive cooling (fans) cannot cool the cabinet below ambient temperature; in fact, they can only maintain the interior at a temperature above ambient. If the outside air is 50°C, a fan-cooled cabinet might sit at 60°C or higher, triggering thermal shutdowns.

Furthermore, fine dust and sand are constant threats. An open-loop fan system requires filters. In a high-dust environment, filters clog rapidly, reducing airflow and causing temperatures to spike. The maintenance interval for filter replacement might be every few months, which defeats the purpose of an “unattended” site.

Scenario B: The Coastal Sensor Node

In maritime or coastal deployments, the primary enemy is not just heat, but corrosion. Salt fog can penetrate standard filters, depositing conductive salts on circuit boards (PCBs). This leads to short circuits and premature hardware failure. Even if the ambient temperature is moderate, the requirement here is isolation. The cabinet must be sealed to prevent ingress. Once sealed, the heat generated by the electronics is trapped. Without an active mechanism to remove this heat from the sealed volume, the internal temperature will rise until equilibrium is reached—often well beyond the survival limit of the components.

Decision Matrix: Comparing Cooling Architectures

When designing for these constraints, engineers typically evaluate three primary technologies: Filter Fans, Thermoelectric Coolers (TEC/Peltier), and Micro DC Air Conditioners (Vapor Compression). The following table compares these options based on criteria critical to remote operations.

| Criteria | Filter Fans (Open Loop) | Thermoelectric / Peltier (Closed Loop) | Micro DC Aircon (Compressor) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling Mechanism | Ambient Air Exchange | Solid State Heat Pump | Vapor Compression Cycle |

| Sub-Ambient Capability | Impossible (Internal > Ambient) | Yes (Limited Capacity) | Yes (High Capacity) |

| Sealing Compatibility | Low (Requires Airflow Path) | High (No Air Exchange) | High (No Air Exchange) |

| Dust/Salt Tolerance | Poor (Depends on Filter) | Excellent | Excellent |

| Power Efficiency (COP) | High (Low power draw) | Low (Typically COP < 0.6) | High (Typically COP > 2.0) |

| Heat Load Suitability | Low to High (if Ambient permits) | Low (< 200W typically) | Medium to High (100W–900W+) |

| Best-Fit Scenario | Indoor / Clean / Cool Ambient | Small Enclosures / Low Heat | High Heat / High Ambient / Solar |

Implications of the Matrix:

The data suggests that while fans are energy-efficient, they fail in high-ambient or corrosive environments. Thermoelectric coolers offer sealing but struggle with efficiency and capacity as heat loads increase. For deployments requiring both high ingress protection and the ability to reject significant heat loads (300W+) in hot environments, the vapor-compression cycle used in a Micro DC Aircon often provides the most balanced performance-to-power ratio.

Quick Selection Rules for Design Reviews

Use these conditional rules to narrow your selection during the initial design phase:

- Rule 1: If the target internal temperature is lower than the maximum ambient temperature, you typically require active cooling (Compressor or TEC). Fans are disqualified.

- Rule 2: If the estimated heat load exceeds 200W–300W, a DC compressor solution is usually more energy-efficient than a Thermoelectric cooler due to a higher Coefficient of Performance (COP).

- Rule 3: If the site is powered by batteries or solar, prioritize systems with “soft start” or inverter-driven compressors to avoid high inrush currents that can trip protection circuits.

- Rule 4: If the environment contains conductive dust, salt spray, or corrosive gases, the enclosure must be sealed (closed-loop). Avoid open-loop air exchange.

- Rule 5: If maintenance visits are costly (e.g., helicopter or long drive required), avoid solutions that rely on consumable filters (fans) unless the environment is exceptionally clean.

Unseen Enemies of Uptime: Failure Modes in Remote Cooling

Selecting the wrong cooling architecture often leads to specific, predictable failure modes. Understanding these mechanisms allows engineers to design resilience into the system before the first unit is deployed.

1. The Filter Clogging Spiral (Open Loop)

In fan-cooled systems, the filter is the single point of failure. As dust accumulates, the pressure drop across the filter increases. This reduces the volumetric airflow rate (CFM). Since cooling capacity is directly proportional to mass flow rate, the thermal performance degrades linearly with clogging. Eventually, the airflow drops below the threshold required to remove the heat generated by the equipment, leading to a thermal runaway event. In remote sites, this necessitates a truck roll solely to change a filter—a high operational expense for a low-cost consumable.

2. The Efficiency Trap (Thermoelectric)

While Peltier coolers are robust due to having no moving parts (other than fans), their low efficiency becomes a liability in off-grid scenarios. To pump 300W of heat, a TEC might consume 300W to 500W of electricity. This doubles the power system requirements (solar panels, battery capacity). In contrast, a vapor-compression system might move that same 300W of heat using only 100W–150W of electrical power. Under-sizing the power system for a TEC can lead to battery depletion during cloudy days or extended operational periods.

3. Inrush Current Trips (DC Compressors)

Not all compressors are created equal. Older on/off compressors can draw a locked-rotor current (LRA) that is 5 to 10 times their running current during startup. On a 24V or 48V battery bus, this spike can cause a voltage sag that triggers the undervoltage lockout (UVLO) on sensitive telecom equipment, causing the site to reboot. Modern Micro DC Aircon solutions utilizing BLDC inverter rotary compressors typically mitigate this via soft-start algorithms, ramping up speed gradually to keep current draw stable.

Engineering Fundamentals: The Vapor Compression Advantage

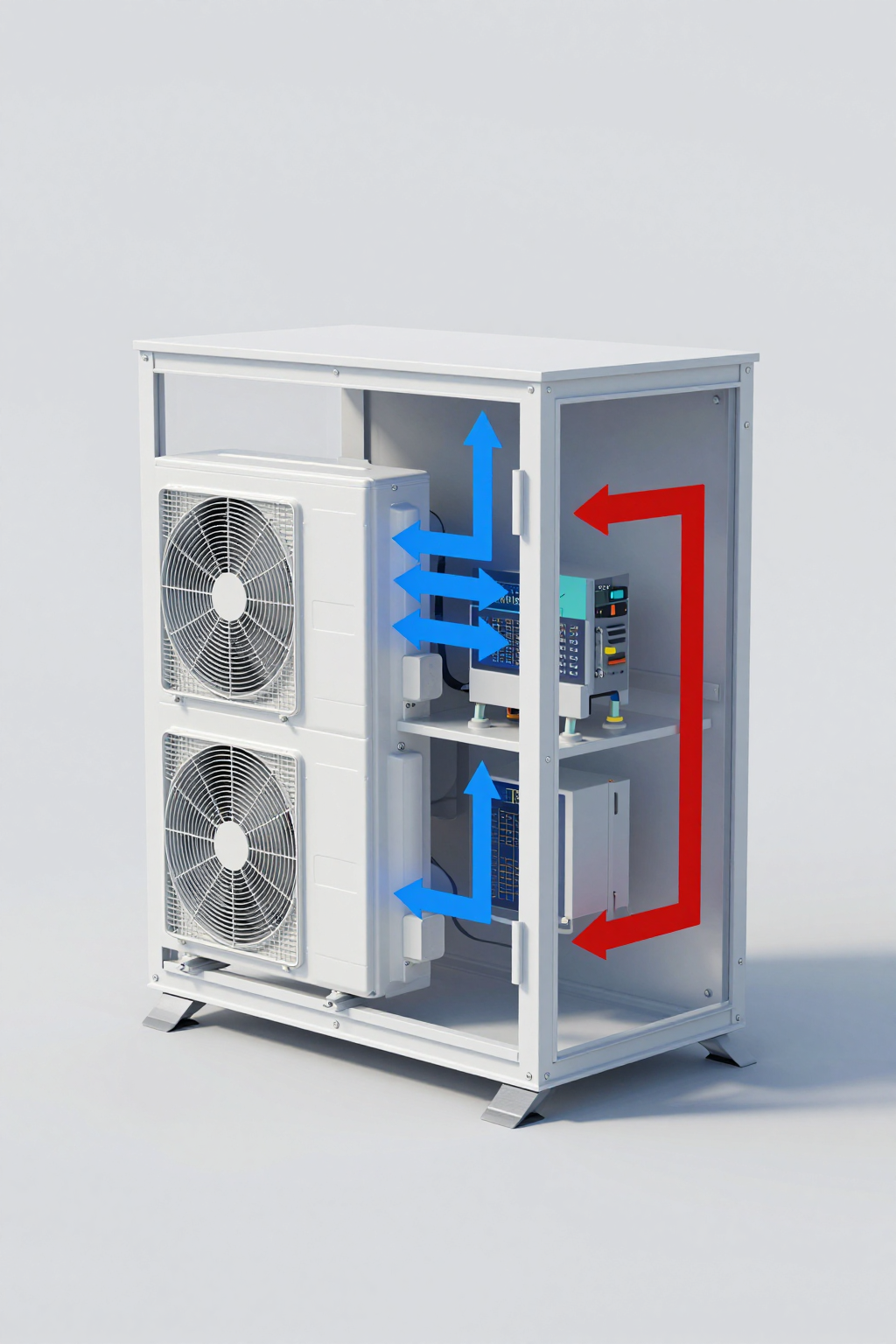

To appreciate why a micro ac for remote outdoor cabinet is often the preferred choice for harsh environments, we must look at the thermodynamics of the vapor compression cycle. Unlike passive cooling, which relies on the temperature difference between the inside and outside air to drive heat transfer, a compressor-based system uses work (electrical energy) to pump heat against the thermal gradient.

The core advantage lies in the phase change of the refrigerant. When the refrigerant evaporates in the evaporator coil (inside the cabinet), it absorbs a massive amount of latent heat from the internal air. It is then compressed and pumped to the condenser (outside), where it rejects that heat to the ambient air. This process allows the system to maintain an internal temperature of 25°C or 30°C even when the outside air is 55°C.

This capability is often referred to as “temperature headroom.” In a passive system, your headroom is negative (you are always hotter than ambient). In a compressor system, you create positive headroom, ensuring that sensitive components like lithium-ion batteries or fiber switches remain within their optimal thermal envelope regardless of the weather. This extends the lifespan of the electronics and reduces the risk of heat-induced drift or failure.

Sealing Reality Clause: Closed-loop designs avoid air exchange, but overall ingress protection still depends on gasket integrity, cable glands, and installation quality.

Performance Data & Verified Specifications

When specifying a cooling unit, it is critical to align the cooling capacity with the heat load and available voltage. The following table highlights verified specifications for the DV series of Micro DC Air Conditioners, which utilize miniature DC compressors to achieve high density cooling in a compact footprint.

| Model (Pro Series) | Voltage (DC) | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant | Compressor Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC | 12V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1920E-AC | 24V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1930E-AC | 48V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV3220E-AC | 24V | 550W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

Note: Cooling capacity varies by model and operating conditions. The values above represent nominal ratings.

These units integrate the driver board (PCB) for control, allowing for variable-speed operation. This is particularly valuable in partial-load conditions. If the cabinet is only generating 200W of heat (e.g., at night or during low traffic), the inverter compressor can slow down, reducing power consumption and preventing the rapid cycling that wears out traditional fixed-speed compressors.

Field Implementation Checklist: Best Practices

Successful deployment requires more than just buying the right part number. Integration details often determine whether a system survives the field. Based on field data, here is a checklist for integrators:

Mechanical Integration

- Gasket Compression: Ensure the mounting surface is flat and rigid. Uneven torque on mounting bolts can warp the flange, creating gaps in the gasket where dust or moisture can enter.

- Condensate Management: Active cooling removes humidity, creating condensate. Ensure the drain tube is routed correctly to the exterior and includes a trap or valve to prevent insects or air from entering through the drain line.

- Airflow Short-Cycling: Do not mount the AC unit such that the cold air discharge blows directly into a solid wall or obstruction. This causes “short-cycling,” where the unit thinks the cabinet is cool and shuts off prematurely, while hot spots remain elsewhere.

Electrical Integration

- Cable Sizing: DC motors draw current. Undersized cables lead to voltage drop. If the voltage at the unit terminals drops below the cutoff threshold during compressor startup, the unit will fault. Calculate voltage drop based on cable length and peak current.

- Circuit Protection: Always use a dedicated fuse or breaker sized according to the manufacturer’s maximum current rating.

Thermal Optimization

- Solar Shielding: A simple sunshield or double-wall construction on the cabinet can reduce the solar heat load by 50% or more. This allows you to use a smaller, lower-power cooling unit.

- Insulation: Insulate the cabinet walls. A metal cabinet acts as a radiator (or absorber). Insulation minimizes the impact of ambient temperature swings on the internal volume.

Expert Field FAQ

Q: Can I run a Micro DC Aircon directly from a solar panel?

A: Typically, no. While they are DC-powered, the voltage from a solar panel fluctuates wildly with irradiance. A battery bank or stable DC power supply is usually required to act as a buffer and provide stable voltage within the unit’s operating range (e.g., 24V).

Q: How does a sealed enclosure handle pressure changes?

A: As the air inside heats and cools, pressure changes. In perfectly sealed enclosures, this can stress seals. In many deployments, a small Gore-Tex style breather vent is used to equalize pressure while blocking moisture and dust ingress.

Q: What is the maintenance interval for a Micro DC Aircon?

A: Unlike filter fans, the internal loop is sealed and requires no cleaning. The external condenser coil may need occasional cleaning if deployed in environments with heavy cottonwood, mud, or sticky debris, but generally, the maintenance interval is significantly longer than filter-based systems.

Q: Why use 48V instead of 12V?

A: For higher capacity systems (450W+), 48V is often preferred to reduce current draw. Lower current means thinner cables and less voltage drop over long runs, which is common in telecom towers or large remote sites.

Q: Is a heater also required?

A: Depends on the location. In deserts, nights can be freezing. Some electronics have a minimum operating temperature. A separate heater or a reverse-cycle unit might be needed if the internal heat load isn’t enough to keep the cabinet warm during cold snaps.

Q: How do I size the unit for a micro ac for remote outdoor cabinet application?

A: You need to calculate the total heat load: Internal Heat Dissipation (Watts) + Solar Load (Watts) + Heat Transfer through walls (Watts). If you don’t have these numbers, estimating based on component power ratings is a good start, but adding a safety margin is wise.

Conclusion: The Logic of Resilience

The decision to deploy a micro ac for remote outdoor cabinet cooling is rarely about luxury; it is about the mathematics of reliability. While the upfront cost of a compressor-based unit is higher than a fan, the return on investment is realized through the elimination of truck rolls, the extension of battery and component life, and the preservation of uptime in environments that would destroy standard equipment.

For engineers building for the edge, the path forward involves acknowledging the severity of the environment. If the site is hot, dusty, and remote, passive methods are often a false economy. By selecting a closed-loop, active cooling solution like the Micro DC Aircon, you decouple the internal operating conditions from the external chaos, ensuring that your critical infrastructure performs as predictably in the middle of a desert as it does in the lab.

Request Sizing Assistance

Sizing a thermal solution for off-grid or remote applications requires precision to avoid over-taxing your power budget. To get a defensible recommendation, prepare the following inputs and consult with our engineering team:

- Ambient Conditions: Max expected ambient temperature and solar exposure level.

- Target Temperature: Maximum allowable internal temperature for your most sensitive component.

- Heat Load: Total power dissipation of internal electronics (Watts).

- Power Source: Available DC voltage (12V/24V/48V) and current limits.

- Sealing Target: Desired ingress protection level (e.g., NEMA 4/4X equivalent).

- Service Expectations: Desired maintenance interval (e.g., 1 year, 5 years).

0 条评论