Angle: The decision moment for an OEM engineer is choosing between passive/vented cooling and active, closed-loop air conditioning for a sealed kiosk. The primary failure modes are screen blackouts and payment processor resets due to solar load and internal heat buildup. The dominant constraint is maintaining a sealed enclosure against environmental ingress while managing a high thermal delta.

Solving Outdoor Terminal Overheating: A Guide to the Micro DC Air Conditioner for Outdoor Kiosk Design

For engineers designing outdoor kiosks, payment terminals, and digital signage, thermal management is not a feature—it’s a foundational requirement for operational uptime. A terminal that overheats in direct summer sun is one that fails to process transactions, display critical information, and ultimately, generate revenue. The stakes are high, involving not just lost income but also the significant costs of field service calls and damage to brand reputation. When a customer-facing device fails, the consequences are immediate and visible. The challenge lies in removing heat from sensitive electronics that are housed within a necessarily sealed enclosure, protecting them from rain, dust, and humidity.

By the end of this technical guide, you will be able to determine the specific environmental and operational thresholds that make an active cooling solution, such as a micro DC air conditioner for outdoor kiosk enclosures, a more reliable and cost-effective choice than traditional fan-based or passive methods. In this article, we prioritize long-term system reliability and component longevity by analyzing the physics of closed-loop cooling, because the cost of a field failure almost always exceeds the initial investment in a robust thermal solution.

Deployment Context: Two Common Scenarios

The need for advanced thermal management is not theoretical. It arises from specific, challenging field conditions where simpler solutions have proven inadequate.

Scenario A: QSR Drive-Thru Terminal in a High-Heat Climate

A quick-service restaurant deploys a new payment terminal in Phoenix, Arizona. The enclosure is sealed to protect against dust and monsoon rains. By mid-afternoon, with ambient temperatures hitting 105°F (40°C) and direct solar radiation adding significant heat load, internal temperature can approach component limits under peak sun. The primary failure points are the LCD screen, which becomes unreadably dark, and the payment processing module, which begins to intermittently reset. The core constraint is the massive solar load combined with the heat generated by the high-brightness screen and processor, all trapped within a sealed box with no way for the heat to escape.

Scenario B: Coastal Transit Ticketing Kiosk

A municipal transit authority installs ticketing kiosks along a shoreline in Florida. To combat the corrosive salt spray and high humidity, the enclosures are designed to be tightly sealed. The initial design used a simple filtered fan system, assuming it would provide enough airflow. Within six months, service calls surged. Technicians found that the fans were pulling in fine, salt-laden mist that bypassed the filters, leading to corroded PCB traces and connector pins. The system was failing not from heat alone, but from environmental contamination introduced by an inappropriate cooling method. The dominant constraint here is the need for a truly sealed enclosure, making any open-loop air exchange a liability.

Common Failure Modes and System Constraints

When designing for outdoor deployments, engineers must anticipate a range of potential failures. Understanding the causal chain from symptom to root cause is critical for selecting the right thermal management strategy. Here are common failure modes, ranked by impact:

- Symptom: LCD Screen Blackout or Artifacting → Cause: Display controller or liquid crystals exceed maximum operating temperature. → Why it matters: The kiosk is rendered completely unusable, halting all user interaction and revenue generation.

- Symptom: Payment Processor Resets → Cause: CPU or chipset initiates thermal throttling or emergency shutdown. → Why it matters: Leads to failed transactions, system downtime, and data corruption, requiring a costly on-site or remote reboot.

- Symptom: Unresponsive or Erratic Touchscreen → Cause: High temperatures cause drift in the capacitive sensing layer. → Why it matters: A primary user interface becomes unreliable, leading to user frustration and abandoned transactions.

- Symptom: Premature Power Supply (PSU) Failure → Cause: Electrolytic capacitors degrade exponentially faster at elevated temperatures. → Why it matters: Causes system-wide instability and is often difficult to diagnose remotely, necessitating a service call to replace the unit.

- Symptom: Corroded Connectors and PCBs → Cause: Humid, salty, or polluted air is actively drawn into the enclosure by open-loop fan systems. → Why it matters: Causes intermittent, hard-to-trace faults that lead to premature end-of-life for the entire electronics package.

- Symptom: Reduced Performance of Wireless Modules (Cellular, Wi-Fi) → Cause: Power amplifiers in radio modules become less efficient as they heat up. → Why it matters: Can lead to dropped connections, slower data throughput, and unreliable network communication for transaction processing or remote management.

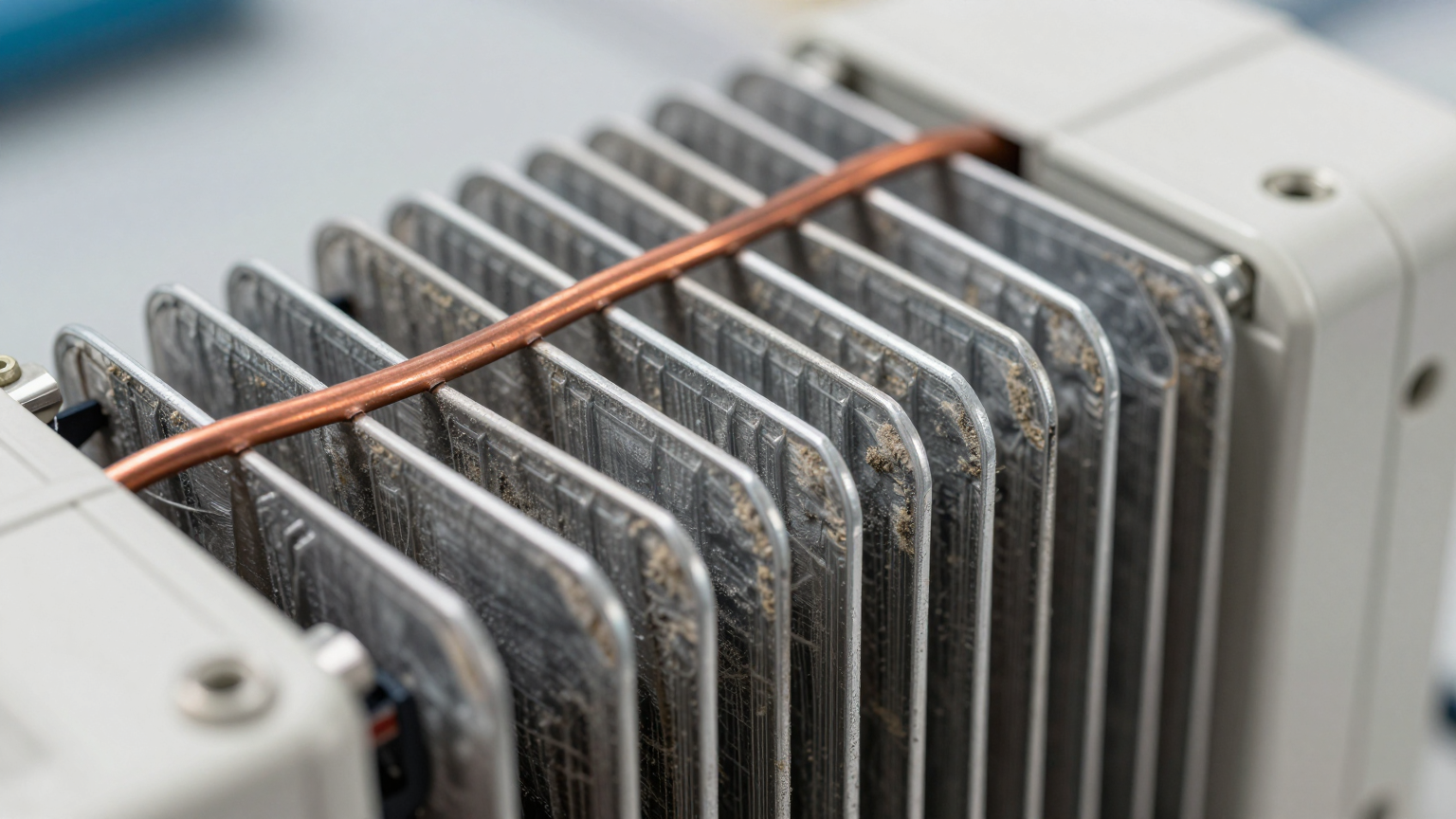

- Symptom: Dust-Clogged Heatsinks and Fans → Cause: Ingress from improperly sealed or fan-and-filter systems. → Why it matters: A layer of dust acts as an insulator, dramatically reducing the efficiency of any internal air circulation and accelerating component overheating.

The Engineering Fundamentals of Sealed Enclosure Cooling

The central decision in kiosk thermal management revolves around one concept: closed-loop versus open-loop cooling. Understanding this distinction is key to avoiding the failure modes described above.

Open-Loop Cooling: This method, typified by fans and filters, works by exchanging air between the inside of the enclosure and the outside environment. It pulls in ambient air to cool components and exhausts the heated internal air. While simple and low-cost, it has two fundamental weaknesses. First, it directly compromises the enclosure’s seal, creating a pathway for dust, moisture, and corrosive agents. Second, its effectiveness is capped by the ambient air temperature. A fan can only cool a component to a temperature *above* the air it’s using. If the outside air is 40°C, it’s impossible for a fan to cool an internal processor to 35°C.

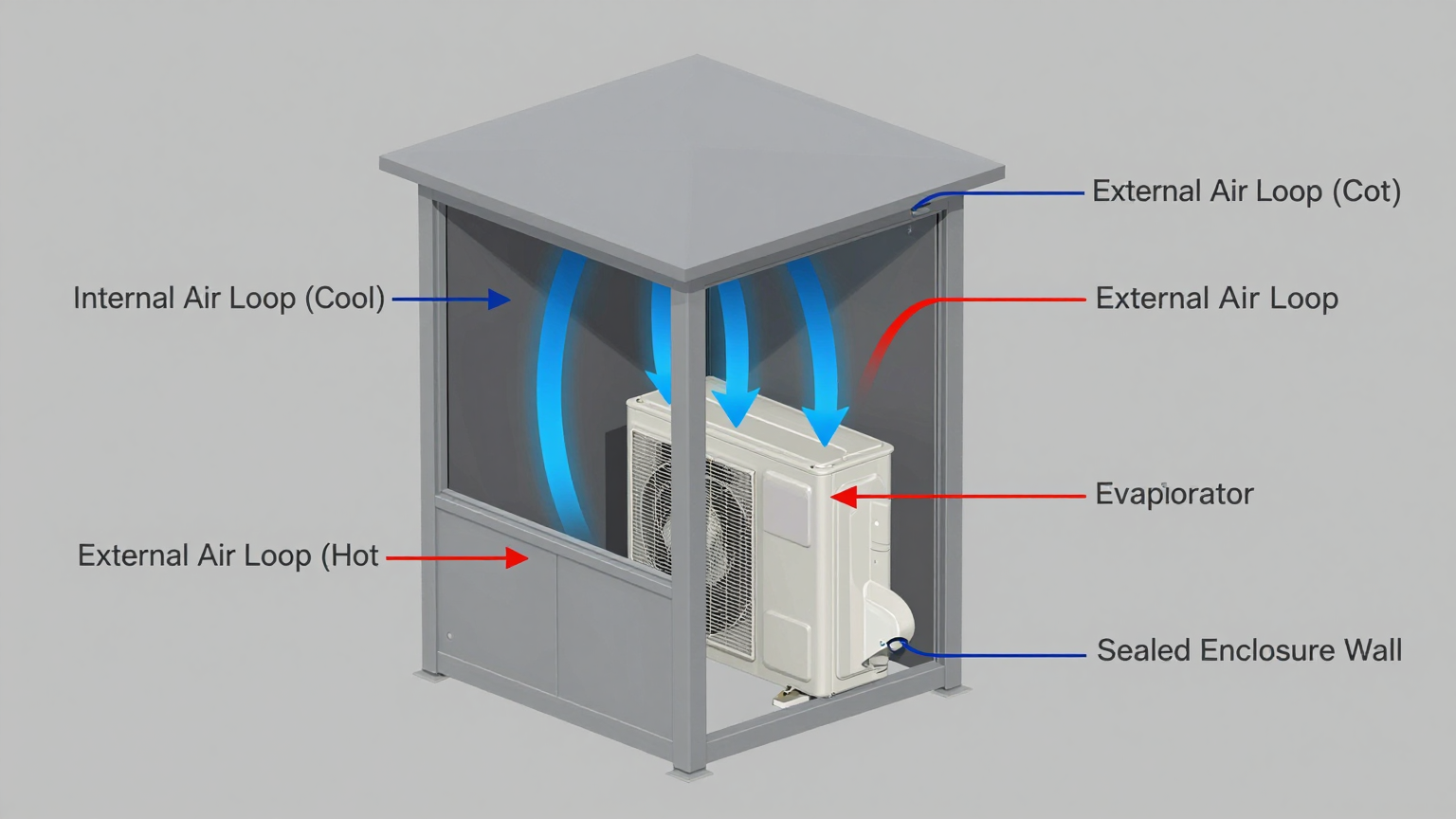

Closed-Loop Cooling: This method, employed by devices like a micro DC air conditioner, completely isolates the internal and external air. It functions by recirculating and actively cooling the air already inside the enclosure. Heat is absorbed from the internal air, transferred through a refrigerant cycle, and then rejected into the outside environment via a separate external air loop. This approach maintains the integrity of the enclosure’s IP/NEMA seal and, crucially, can cool the internal temperature to well below the ambient outdoor temperature.

A common misconception among design teams is that if a system is overheating, simply adding a more powerful fan will resolve the issue. This correction often fails in the field. If the problem is high ambient temperatures or the need for a sealed box, a fan is fundamentally the wrong tool. The solution requires a shift in methodology from simple air exchange to active, refrigerant-based heat removal—the core function of a micro DC aircon for sealed kiosk enclosure.

Specification Gateway for Active Cooling Units

When the engineering requirements point toward an active, closed-loop solution, the selection process becomes data-driven. Evaluating the specifications of a micro DC air conditioner for outdoor kiosk applications requires focusing on the parameters that directly impact integration and performance. Key considerations are the available DC voltage from your system’s power bus, the required cooling capacity to overcome the total heat load, and the physical dimensions for mounting.

The table below shows baseline parameters for representative models in the Micro DC Aircon series. Note that nominal cooling capacity is a critical metric, which must be sized to exceed the combined heat from internal electronics and external solar gain.

| Model (Example) | Input Voltage | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC (Pro) | 12V DC | 450W | R134a | Varies by configuration |

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V DC | 450W | R134a | Varies by configuration |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V DC | 450W | R134a | Varies by configuration |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V DC | 550W | R134a | Varies by configuration |

Engineering Selection Matrix: Logic Gates for Integration

A lead engineer must navigate a series of critical decision points to arrive at a viable thermal solution. These logic gates are not about picking a product, but about defining the problem so that the solution becomes self-evident.

Logic Gate 1: The Sealing Mandate

- Constraint Gate: Does the kiosk require a NEMA or IP rating to protect against dust, moisture, or wash-downs? Is it being deployed in a corrosive environment (e.g., coastal or industrial)?

- Decision Trigger: If the answer is yes, any solution that requires venting the enclosure (like a fan-and-filter system) introduces an unacceptable risk of contamination and long-term failure.

- Engineering Resolution: The selection is often narrowed to closed-loop systems. This path prioritizes protecting the electronics from the external environment. The choice is now between a passive air-to-air heat exchanger or an active air conditioner.

- Integration Trade-off: Committing to a sealed design increases the initial system complexity and cost but drastically reduces the likelihood of field failures from environmental factors, lowering the total cost of ownership.

Logic Gate 2: The Below-Ambient Requirement

- Constraint Gate: What is the maximum allowable internal temperature for reliable operation (e.g., 40°C), and what is the maximum expected ambient temperature at the deployment site (e.g., 50°C)?

- Decision Trigger: If the required internal temperature is lower than the maximum external ambient temperature, passive cooling methods are physically incapable of meeting the requirement. A heat exchanger can only approach ambient temperature; it can never go below it.

- Engineering Resolution: This is the strong trigger for active, refrigerant-based cooling. A vapor-compression system is the often the most practical way to create a temperature differential where the inside of the enclosure is cooler than the outside world. This makes a micro dc cabinet air conditioner kiosk the primary candidate.

- Integration Trade-off: This path requires allocating budget for a higher power draw on the DC bus and a higher initial component cost. However, it is often the only way to help maintain system uptime in challenging thermal environments.

Logic Gate 3: The Heat Load Calculation

- Constraint Gate: What is the total heat load that must be removed? This is the sum of the power dissipated by all internal electronics (processor, display, power supply, etc.) plus the estimated solar load on the enclosure’s surfaces.

- Decision Trigger: Once the total heat load is calculated in watts, a cooling unit must be selected with a nominal capacity that exceeds this value by a recommended safety margin (typically 20-25%) to account for component aging and extreme conditions.

- Engineering Resolution: For a calculated total load of 350W, an engineer would look for a unit with a capacity of at least 420W. For instance, a 450W unit like the DV1920E-AC (Pro) 24V model could be a suitable candidate for evaluation in a system with a 24V power architecture.

- Integration Trade-off: Accurate heat load calculation is paramount. Undersizing the unit guarantees thermal failure under peak load. Grossly oversizing it wastes space, power, and money. Diligence in the calculation phase prevents costly errors in the integration phase.

Implementation and Verification Checklist

Successfully integrating a micro DC air conditioner for outdoor kiosk designs extends beyond selection. It requires meticulous attention to mechanical, electrical, and thermal details during assembly and validation.

- Mechanical Integration

- Mounting Surface: Ensure the mounting surface is flat and rigid to prevent torqueing the unit’s frame.

- Gasket Seal: Use the specified gasket and follow torque patterns for mounting screws to create a watertight and airtight seal, preserving the enclosure’s NEMA/IP rating.

- Airflow Integrity: Verify that the internal (cold side) and external (hot side) airflows are completely unobstructed. Do not place other components or cable bundles directly in front of the air intake or exhaust vents.

- Electrical Integration

- Power Budgeting: The DC power supply must be rated to handle the compressor’s inrush current on startup, not just its steady-state running current.

- Circuit Protection: Install an appropriately rated fuse or circuit breaker on the power line to the unit, as specified in its documentation.

- Wiring Practices: Use the recommended wire gauge to minimize voltage drop. Route wires securely, protecting them from sharp edges and vibration.

- Thermal Validation

- Sensor Placement: For testing, place thermocouples on the most heat-sensitive components (e.g., CPU case, display driver IC), not directly in the path of the cold air output. This gives a true reading of component temperature.

- Acceptance Testing: Conduct a full-load system test in a thermal chamber set to the maximum specified ambient temperature. Monitor component temperatures to ensure they remain well within their operational limits.

- Maintenance Considerations

- Condenser Coil Access: Design the kiosk so that the external condenser coils are accessible for periodic cleaning. A buildup of dust, pollen, or debris will significantly degrade cooling performance.

- Visual Inspection: Schedule periodic checks for the integrity of the mounting gasket and to ensure both internal and external fans are operational.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Should I use a thermoelectric (Peltier) cooler or a micro DC air conditioner for outdoor kiosk applications?

For heat loads below approximately 100W and small temperature differentials, thermoelectric coolers can be viable. However, for the higher heat loads typical of kiosks (displays, processors) and the need to cool below ambient, vapor-compression systems like a micro DC air conditioner are significantly more energy-efficient and effective.

2. How does this type of unit maintain the enclosure’s IP/NEMA rating?

It is designed for this specific purpose. The unit mounts through a cutout in the enclosure wall, but a compression gasket seals the flange against the exterior surface. The internal and external air paths are completely separate, so no outside air enters the electronics compartment, preserving the seal.

3. What is the plan for condensation management?

This depends on the deployment’s humidity. Many units are designed with a hot-side condensate evaporation system, where any collected moisture is boiled off by the heat of the condenser coil. In extremely humid environments, a model with a dedicated drain port may be a better choice to route condensation away safely.

4. How does direct sunlight impact performance?

Direct sunlight adds a significant amount of heat to the enclosure, known as solar load. This load (in watts) must be calculated and added to the internal electronic heat load when sizing the air conditioner. Designing a simple, reflective sun shield or positioning the kiosk to minimize direct afternoon sun exposure can greatly improve thermal performance.

5. What is the most critical measurement I need before selecting a cooling unit?

The total heat load. You must sum the thermal design power (TDP) or actual power consumption of every component inside the enclosure (CPU, GPU, screen, power supply, etc.). An inaccurate heat load calculation is the most common cause of selecting an undersized unit.

6. How can I validate the cooling performance after installation?

The most reliable method is to instrument the kiosk with thermocouples on key components and run the system at 100% load (e.g., running a benchmark or video loop) on a day that meets the maximum design ambient temperature. If all component temperatures stabilize within their specified operating range, the solution is validated.

7. Is a fan with a filter ever a viable alternative for sealed enclosure cooling for a kiosk?

It can be, but only in very specific circumstances: the external environment must be cool and clean, the electronics must be able to operate reliably at temperatures above ambient, and there must be no requirement for a true NEMA/IP seal against moisture or fine particulates.

Conclusion: Matching the Solution to the Constraints

The selection of a thermal management system for an outdoor kiosk is a direct function of the environmental and operational constraints. While simple fans are sufficient for benign, open-air applications, they become a liability when faced with the realities of heat, humidity, dust, and the need for a sealed enclosure.

A micro DC air conditioner for outdoor kiosk systems becomes the most robust engineering choice when two conditions are met: the enclosure must remain sealed against the elements, and the internal electronics must be maintained at a temperature near or below the external ambient temperature. By using a closed-loop, active cooling system, engineers can eliminate environmental contamination as a failure vector and overcome the physical limitations of passive cooling. This approach directly addresses the primary causes of field failure, ensuring the kiosk remains operational, reliable, and profitable even in the most demanding conditions.

If you are facing challenges with outdoor terminal enclosure overheating, our engineering team can assist with heat load analysis and recommend a thermal management solution tailored to your enclosure geometry, DC power constraints, and specific deployment environment. Contact us to discuss your project’s unique requirements.

0 条评论