For OEM engineers designing outdoor electronics cabinets, thermal management is rarely just about temperature. It is a simultaneous battle against heat, dust, and—perhaps most insidiously—moisture. While ingress protection (IP) ratings focus on keeping external water out, they often distract from the internal threat: condensation. Implementing effective dew point sealed enclosure cooling requires a nuanced understanding of psychrometrics, pressure differentials, and the behavior of active cooling systems in variable climates.

In harsh deployment scenarios—from tropical telecom towers to offshore sensor arrays—the air inside a “sealed” enclosure is never truly dry unless actively purged or conditioned. When an active cooling system, such as a Micro DC Aircon, drives internal temperatures down, it risks crossing the dew point threshold. If the evaporator coil or, worse, the sensitive electronics themselves become the coldest surface in the cabinet, phase change occurs. Water vapor becomes liquid water.

This article outlines the engineering logic for managing moisture in closed-loop systems. We will examine how to balance the requirement for sub-ambient cooling with the physical inevitability of condensation, ensuring that your dew point sealed enclosure cooling strategy protects uptime rather than compromising it.

Deployment Context: The Moisture Paradox

To understand the risks, we must look at where these systems live. Lab conditions rarely replicate the diurnal cycling and humidity loads of the field.

Scenario A: The Tropical Telecom Cabinet

Consider a battery backup and switching cabinet deployed in Southeast Asia. Ambient temperatures hover around 35°C (95°F) with relative humidity often exceeding 85%. The enclosure is rated IP55 or NEMA 4. During the day, solar loading drives internal temperatures up. A Micro DC Aircon engages to keep the batteries at an optimal 25°C.

Here, the cooling target (25°C) is significantly below the ambient dew point. If the cabinet is not perfectly airtight (and few are), vapor pressure drives moisture into the enclosure. The cooling unit’s evaporator coil becomes a dehumidifier. If the condensate is not managed—drained or evaporated—it pools inside the cabinet, eventually threatening the DC bus bars at the bottom of the rack.

Scenario B: The High-Latitude Sensor Station

In a coastal deployment in Northern Europe, the challenge shifts. The ambient air is cool but damp (salt fog). The electronics generate intermittent heat. When the system is idle at night, the enclosure cools down. As the internal air volume contracts, it creates a vacuum, pulling damp, salty outside air in through microscopic gaps in gaskets or cable glands. When the electronics wake up and heat generates, or when the sun hits the cabinet, that moisture might remain as vapor until the next cool-down cycle, where it condenses on the enclosure walls or PCBs. Here, the “sealed” nature of the box traps moisture in rather than keeping it out.

Decision Matrix: Cooling Technologies and Moisture Control

Selecting a thermal management strategy involves weighing cooling capacity against moisture risks. The table below compares common approaches for outdoor, sealed enclosures.

| Technology | Sub-Ambient Capability | Sealed Enclosure Compatibility | Moisture/Condensate Behavior | Typical Application Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Fans (Open Loop) | None (Always > Ambient) | Low (Depends on filter media) | High Risk: Continuously introduces ambient humidity. No condensing surface to remove it. | Indoor or benign outdoor climates; low heat density. |

| Air-to-Air Heat Exchanger | None (Always > Ambient) | High (Closed Loop) | Neutral: Does not dehumidify. Internal humidity tracks ambient dew point but avoids direct ingress. | Telecom cabinets where T_internal > T_ambient is acceptable. |

| Thermoelectric (Peltier) | Yes (Limited Delta T) | High (Closed Loop) | Active Condensing: Cold side condenses moisture. Low capacity means slow dehumidification. | Small enclosures, low heat loads (<100W). |

| Micro DC Aircon (Compressor) | Yes (High Delta T) | High (Closed Loop) | Active Dehumidifying: Evaporator coil actively strips moisture. Requires drainage management. | High heat loads (100W–900W), batteries, lasers, critical comms. |

Implication: If you require sub-ambient temperatures (e.g., for battery longevity), you are implicitly choosing a technology that will generate condensate. Your design must account for water removal.

Quick Selection Rules for Moisture Management

- If the target internal temperature is below the ambient dew point, condensation will occur on the coldest surface.

- If you use a compressor-based solution (Micro DC Aircon), ensure the evaporator has a dedicated condensate path (drip tray + drain).

- If the enclosure is exposed to wide temperature swings, a pressure compensation element (breather vent) is often necessary to prevent seal failure.

- If the electronics are sensitive to any moisture, conformal coating is a secondary defense, not a primary solution.

- If the system runs intermittently, consider a hygrostat-controlled heater to prevent condensation during off-cycles.

- Closed-loop designs avoid air exchange, but overall ingress protection still depends on gasket integrity, cable glands, and installation quality.

Unseen Enemies of Uptime: Failure Modes

When dew point sealed enclosure cooling is mismanaged, the failure modes are rarely immediate thermal shutdowns. They are slow, corrosive processes that degrade reliability over months.

- Dendrite Growth & Electrochemical Migration: In the presence of moisture and DC voltage, metal ions can migrate between traces on a PCB, growing conductive filaments (dendrites). This leads to intermittent shorts that are notoriously difficult to diagnose.

- Sensor Drift: Humidity fluctuations can affect the calibration of sensitive optical or chemical sensors inside the enclosure, leading to erroneous data before the system actually fails.

- Pooling & Corrosion: If condensate forms on the cooling unit but has nowhere to go, it drips. Often, it pools at the bottom of the cabinet, corroding the enclosure floor, grounding studs, or bottom-mounted battery terminals.

- Filter/Coil Clogging (The Thermal Feedback Loop): In systems that are not perfectly sealed, dust ingress combined with wet cooling coils creates “mud.” This sludge blocks airflow through the evaporator, reducing cooling capacity, which causes the compressor to run longer, generating more condensate in a vicious cycle.

Engineering Fundamentals: The Physics of the Cold Surface

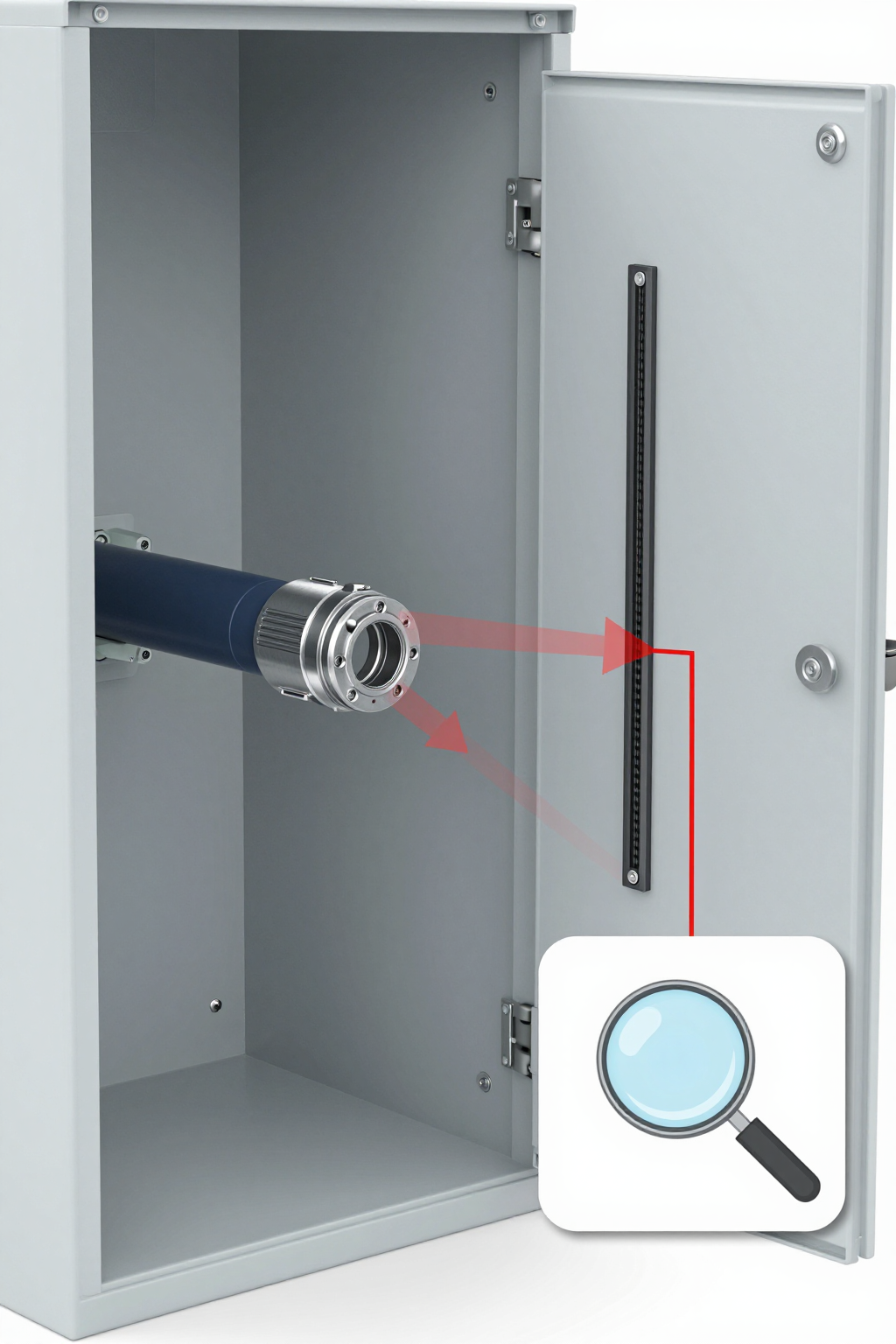

To master dew point sealed enclosure cooling, one must accept that the cooling unit is essentially a water magnet. In a vapor-compression cycle—used by Micro DC Aircons and Miniature DC Compressors—the refrigerant expands in the evaporator coil, dropping its surface temperature significantly below the air temperature inside the cabinet.

This is a feature, not a bug. By ensuring the evaporator coil is the coldest point in the system, we force condensation to happen there rather than on the PCB. The coil acts as a sacrificial surface for moisture. The engineering challenge is purely mechanical: gravity. You must capture that water and route it out of the sealed environment without creating a hole that violates the IP rating.

Furthermore, the concept of “Delta T” (temperature headroom) applies to moisture as well. A high-capacity compressor system, like those using the DV1920E-AC, pulls down temperature quickly. This rapid cooling can sometimes flash-condense moisture if the air volume is humid. Variable-speed inverters help here; by modulating the compressor speed, the system can maintain a steady surface temperature that dehumidifies continuously rather than shock-cooling the air.

Performance Data & Verified Specs

When sizing a solution for a moisture-prone environment, cooling capacity (Watts) is the primary metric, but the voltage and refrigerant type also play roles in efficiency and safety. The following parameters from the Arctic-tek Research Brief highlight the capabilities of the Micro DC Aircon series, which are often selected for these applications due to their ability to handle latent (moisture) loads alongside sensible (heat) loads.

| Model (Series Example) | Voltage (DC) | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant | Compressor Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC (Pro) | 12V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 550W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

Note: Capacity varies by model and operating conditions. The “Pro” designation typically indicates integrated driver boards for precise control.

The use of BLDC inverter rotary compressors allows these units to adjust speed based on load. In high-humidity startups, the compressor can ramp up to remove heat and moisture quickly, then settle into a lower speed to maintain equilibrium, preventing the “sawtooth” temperature profile that often exacerbates condensation on electronics.

Field Implementation Checklist

Successful deployment of Micro DC Aircon systems in sealed enclosures requires attention to mechanical detail. Use this checklist during the design review phase.

Mechanical & Sealing

- Drainage Path: Does the cooling unit have a built-in condensate drain? Is it routed through a trap or a one-way valve to prevent air/dust ingress?

- Gasket Integrity: Are you using continuous-pour gaskets or high-quality EPDM strips? Butt-joints in gaskets are common failure points for moisture ingress.

- Pressure Equalization: Have you installed a hydrophobic breather vent (e.g., ePTFE membrane)? This allows air to expand/contract without stressing seals or sucking in moisture.

Thermal & Control

- Sensor Placement: Place the temperature sensor in the return airflow path, not directly in front of the cold supply air, to prevent short-cycling.

- Hysteresis Settings: Avoid tight on/off bands. Allow the compressor to run long enough to actually dehumidify the air, not just cool it.

- Insulation: Insulate the enclosure walls. This prevents the inner wall surface from becoming a condensing plane when outside temperatures drop rapidly.

Electrical

- Cable Glands: Use rated cable glands for all penetrations. A single open cable pass-through can admit liters of water vapor over a year.

- Conformal Coating: Treat PCBs as if they will get wet. It is a cheap insurance policy against the inevitable moisture that bypasses other defenses.

Expert Field FAQ

Q: Can I just seal the enclosure 100% hermetically to stop moisture?

A: In theory, yes. In practice, it is nearly impossible for large cabinets. Pressure differentials caused by heating/cooling cycles will eventually force air through the weakest seal. It is usually better to design for “breathing” through a controlled, filtered, or membrane-protected vent.

Q: How much water does a Micro DC Aircon actually produce?

A: It depends entirely on the infiltration rate and ambient humidity. In a well-sealed box, it might produce a few milliliters initially and then stay dry. In a leaky cabinet in the tropics, it could generate liters per day. Always design for the leaky scenario.

Q: Does the DV1920E-AC run continuously?

A: The BLDC inverter allows it to run at variable speeds. Continuous, low-speed operation is generally better for moisture control than on/off cycling, as it keeps the evaporator coil cold and continuously stripping moisture.

Q: What is the risk of using a 24V system on a 48V battery bank with a converter?

A: Efficiency loss. We typically recommend matching the cooling unit voltage to the native bus voltage (e.g., using a DV1930E-AC for 48V systems) to eliminate the failure point and heat generation of a DC-DC converter.

Q: How do I prevent condensation when the cooling is OFF?

A: This is a critical window. If the cabinet cools down at night, relative humidity spikes. A small anti-condensation heater, controlled by a hygrostat, is the standard solution to keep internal air slightly above the dew point.

Q: Why not just use a Peltier (TEC) cooler?

A: TECs are valid for very small loads. However, their efficiency (COP) is low compared to compressor-based DC condensing units. For loads above 100-200W, the power draw of a TEC becomes prohibitive for most off-grid or battery-backed applications.

Conclusion & System Logic

Managing dew point sealed enclosure cooling is an exercise in controlled physics. You cannot simply “cool” a sealed box without addressing the water vapor that exists within it. The goal is to direct that phase change to a location where it can be managed—the evaporator coil—rather than letting it happen on your expensive electronics.

For most harsh-environment applications requiring 100W to 900W of cooling, a Micro DC Aircon offers the best balance of capacity, efficiency, and active dehumidification. However, the hardware is only half the solution. The integration—specifically drainage, sealing, and pressure management—determines whether the system survives the field.

Request Sizing & Integration Support

Don’t guess at the latent load. Our engineering team can help you model the thermal and moisture behavior of your enclosure. To get a precise recommendation, please prepare the following inputs:

- Ambient Conditions: Max temperature and relative humidity range.

- Heat Load: Estimated internal dissipation (Watts).

- Enclosure Dimensions & Insulation: Size and material (e.g., uninsulated steel vs. double-wall aluminum).

- Power Source: Available voltage (12V, 24V, 48V) and current limits.

- Target Internal Temperature: The maximum allowable temp for your components.

Contact Arctic-tek today to review your dew point sealed enclosure cooling strategy and ensure your deployment is built for resilience.

0 条评论