The Definitive Playbook for Thermal Management of Rugged Electronics

In the world of off-road equipment, autonomous agriculture, and mobile industrial machinery, the failure of an electronic control unit (ECU) is never a minor event. It’s a cascade of lost productivity, potential safety hazards, and costly field service calls. The root cause is often not a flaw in the silicon itself, but a failure of its environment—specifically, a breakdown in the thermal management of rugged electronics. When a processor overheats or a circuit board is contaminated, the entire machine can grind to a halt. The stakes are simply too high for a cooling strategy to be an afterthought.

As an OEM engineer or system integrator, you are tasked with guaranteeing performance in environments that are actively hostile to electronics: extreme temperatures, constant vibration, pervasive dust, and high-pressure washdowns. This guide provides a decision-making framework to help you determine the precise point at which passive cooling methods become a liability and a shift to active, closed-loop cooling is required. By the end of this playbook, you will be able to confidently select a robust cooling architecture that ensures long-term system reliability. In this article, we prioritize system uptime and ingress protection over minimal upfront cost, demonstrating why sealed enclosures in harsh environments demand an active, not passive, approach to thermal management of rugged electronics.

Deployment Context: Where Cooling Strategies Fail

Theoretical designs often meet their match in the unpredictable reality of the field. Here are two common scenarios where conventional cooling approaches prove inadequate, highlighting the need for a more robust strategy for the thermal management of rugged electronics.

Scenario A: The Autonomous Tractor Control Unit

An agricultural tech company deploys a new fleet of autonomous tractors. Their central guidance and control module is housed in a NEMA 4-rated enclosure, cooled by a filtered fan system to handle the 400W heat load from the onboard processors. After one harvest season, reports of erratic behavior begin. A field inspection reveals that fine, abrasive dust has infiltrated the enclosures, bypassing the filter seals. The dust has coated the PCB, creating a thermal blanket and causing intermittent short circuits. The constraint that led to failure was the attempt to reconcile a high-sealing requirement with the need for air exchange, a fundamental conflict in dustproof electronics cooling.

Scenario B: The Mining Haul Truck Communications Hub

A communications hub on a mining haul truck, responsible for telemetry and GPS data, is housed in a fully sealed IP66 enclosure to protect it from daily high-pressure washdowns. The box has no vents and relies on passive radiation from its surface. On hot, sunny days, the system begins dropping its connection. Analysis shows the internal processors are throttling their clock speed as temperatures inside the enclosure climb to 75°C, a full 30°C above the outside air temperature. The dominant constraint was the massive solar load on a completely sealed box, which added a significant external heat source that passive cooling could not overcome, demonstrating a critical failure in the thermal management of rugged electronics.

Common Failure Modes and System Constraints

When designing for mobile and off-road applications, you must anticipate and mitigate the most likely points of failure. These issues are often interconnected, with one problem triggering another. A sound approach to the thermal management of rugged electronics requires understanding these risks.

- Thermal Throttling → High internal ambient temperatures → Reduced processing power, data errors, and system lag.

- Premature Component Failure → Exceeding maximum operating temperatures → Permanent silicon damage, leading to total system failure and costly replacement.

- Dust & Particulate Ingress → Clogged heatsinks and failed fans in vented enclosures → Rapid and catastrophic overheating.

- Moisture & Corrosion → Condensation from temperature swings or direct ingress → Short circuits and long-term degradation of solder joints and PCB traces.

- Vibration & Shock Fatigue → Mechanical stress on fan bearings and cooling mounts → Unexpected mechanical failure of the cooling system.

- Unstable Power Supply → Variable voltage from a vehicle’s alternator and battery bus → Inconsistent cooling performance or damage to sensitive driver electronics.

- Compromised Seals → Gasket failure or damage on vented enclosures → Complete loss of the specified IP or NEMA rating, exposing electronics to the elements.

- High Maintenance Burden → Required cleaning and replacement of filters on fan systems → Increased total cost of ownership and reliance on disciplined service intervals.

Core Engineering Principle: Closed-Loop vs. Open-Loop Cooling

The central decision in rugged thermal management hinges on one question: should the air inside the enclosure mix with the air outside? This choice defines your entire strategy for the thermal management of rugged electronics.

An open-loop system, like a fan with a filter, is simple. It pulls ambient air into the enclosure, passes it over the hot components, and exhausts it. While inexpensive, it creates a direct pathway for environmental contaminants. Every cubic meter of cooling air brings with it dust, moisture, salt, or corrosive gases.

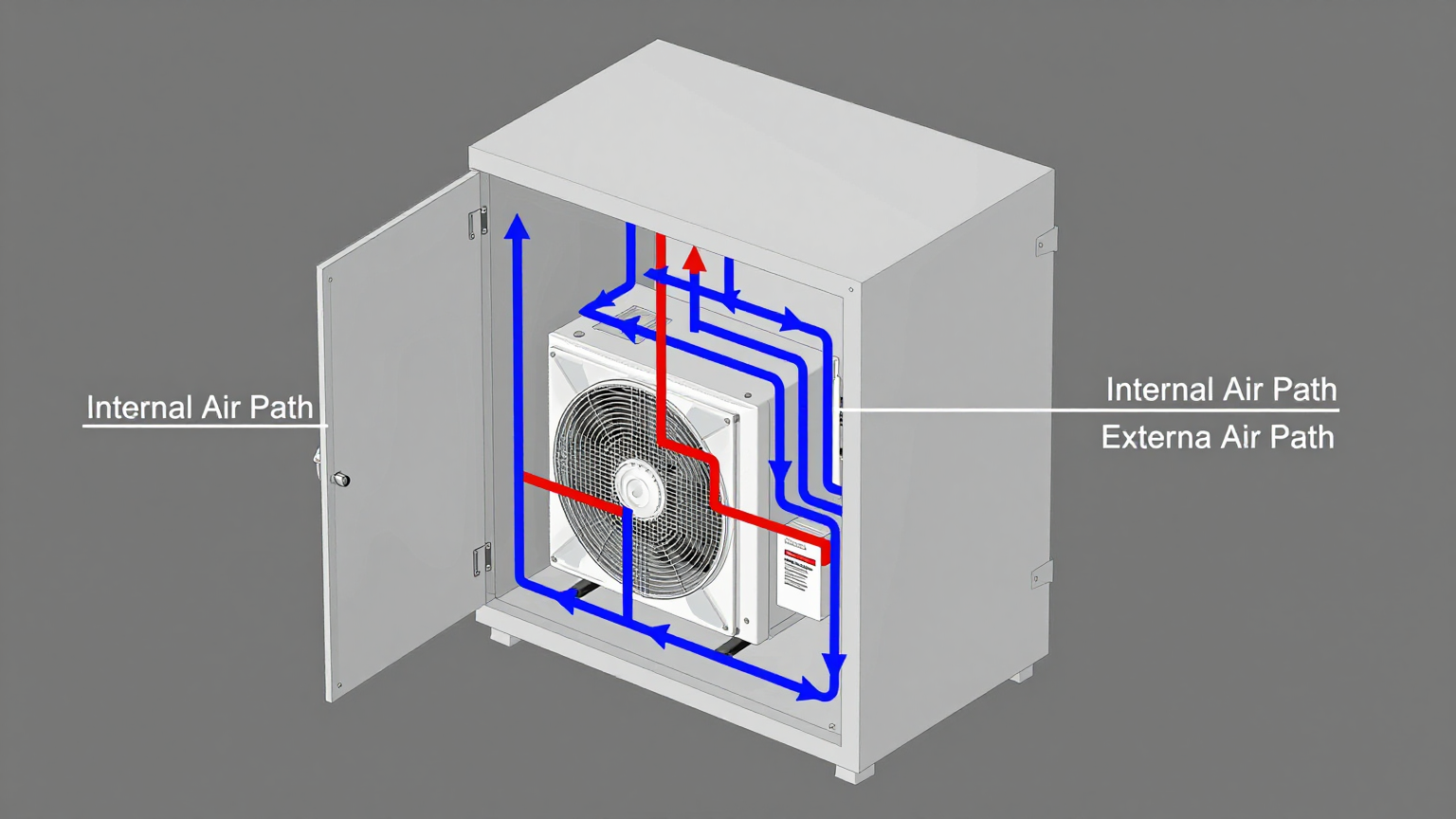

A closed-loop system creates two completely separate air circuits. The internal circuit recirculates clean air within the sealed enclosure, picking up heat from the electronics and transferring it to the cooling unit. The external circuit uses ambient air to remove that collected heat from the cooling unit and exhaust it to the environment. The two air streams never mix. This is the foundational principle of true dustproof electronics cooling and is essential for maintaining the integrity of a sealed enclosure.

The Misconception That Compromises Reliability

A common but flawed belief is that “if my electronics are overheating, I just need a more powerful fan.” This approach often makes the problem worse in rugged environments. A more powerful fan requires a larger vent and pulls in contaminants at a higher rate, accelerating the degradation of the electronics it’s meant to protect. The correction is a shift in thinking: instead of pushing more dirty air through the box, you must remove the heat energy *from* the sealed box. This requires a heat exchanger or an active, refrigerant-based air conditioner, which are cornerstones of effective thermal management for rugged electronics.

Key Specifications for Active Cooling Systems

When you determine that a closed-loop, active solution is necessary, the focus shifts to matching the hardware to the application. When evaluating specs for the thermal management of rugged electronics, the primary goal is to ensure the unit can handle both the electrical and thermal loads of your system. The Micro DC Aircon series, for example, is designed specifically for these compact, high-performance applications.

Here are baseline parameters for representative models. Focus first on the DC voltage to match your vehicle’s power bus. Next, ensure the nominal cooling capacity (in watts) provides a safe margin above your calculated internal heat load. The final selection depends on a complete analysis of your project’s unique constraints.

| Model (Example) | Input Voltage (VDC) | Nominal Cooling Capacity (W) | Refrigerant |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC (Pro) | 12V | 450W | R134a |

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 450W | R134a |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V | 450W | R134a |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 550W | R134a |

Other critical parameters to confirm include the physical dimensions, weight, operating temperature range, and the type of control interface available. These factors are crucial for successful mechanical and electrical integration. A proper approach to the thermal management of rugged electronics depends on this detailed analysis.

Engineering Selection Matrix: Logic Gates for System Design

A structured decision-making process prevents over-engineering and costly underspecification. Use these logic gates to guide your selection from a simple fan to a full active cooling solution. This matrix is a core component of any serious thermal management of rugged electronics strategy.

Logic Gate 1: The Sealing Requirement

- Constraint Gate: Ingress Protection (IP/NEMA Rating) vs. Required Air Exchange.

- Decision Trigger: If the enclosure must be sealed to protect against dust, water spray, or high-pressure washdowns (e.g., IP65, NEMA 4, or higher).

- Engineering Resolution: This immediately disqualifies any open-loop cooling solution that relies on venting ambient air. The choice is now narrowed to two closed-loop options: a passive air-to-air heat exchanger or an active DC air conditioner.

- Integration Trade-off: This decision increases the initial system cost and complexity but is the only way to guarantee the long-term integrity and reliability of the electronics in contaminated environments. It is the first and most important step in dustproof electronics cooling.

Logic Gate 2: The Thermal Delta

- Constraint Gate: Required Internal Temperature vs. Maximum External Ambient Temperature.

- Decision Trigger: If the internal enclosure temperature must be maintained at or, critically, below the external ambient temperature.

- Engineering Resolution: This trigger disqualifies passive heat exchangers. A heat exchanger works on a thermal gradient and can only cool the internal temperature *towards* the ambient temperature; it can never go below it. To achieve a negative thermal delta (e.g., keeping an enclosure at 25°C when it’s 40°C outside), an active, refrigerant-based vapor-compression system like a Micro DC Aircon is mandatory.

- Integration Trade-off: This moves the solution into the realm of active refrigeration, which adds a compact compressor and refrigerant circuit. This increases the unit’s power draw and physical footprint but is the only physics-based solution to the problem. This is a frequent requirement for the thermal management of rugged electronics exposed to direct sun.

Logic Gate 3: The Power Architecture

- Constraint Gate: Available DC Power Budget vs. Cooling System Demand.

- Decision Trigger: If the power source is a variable vehicle bus (e.g., 12V, 24V, or 48V DC) that experiences voltage sags during engine cranking or peaks from the alternator.

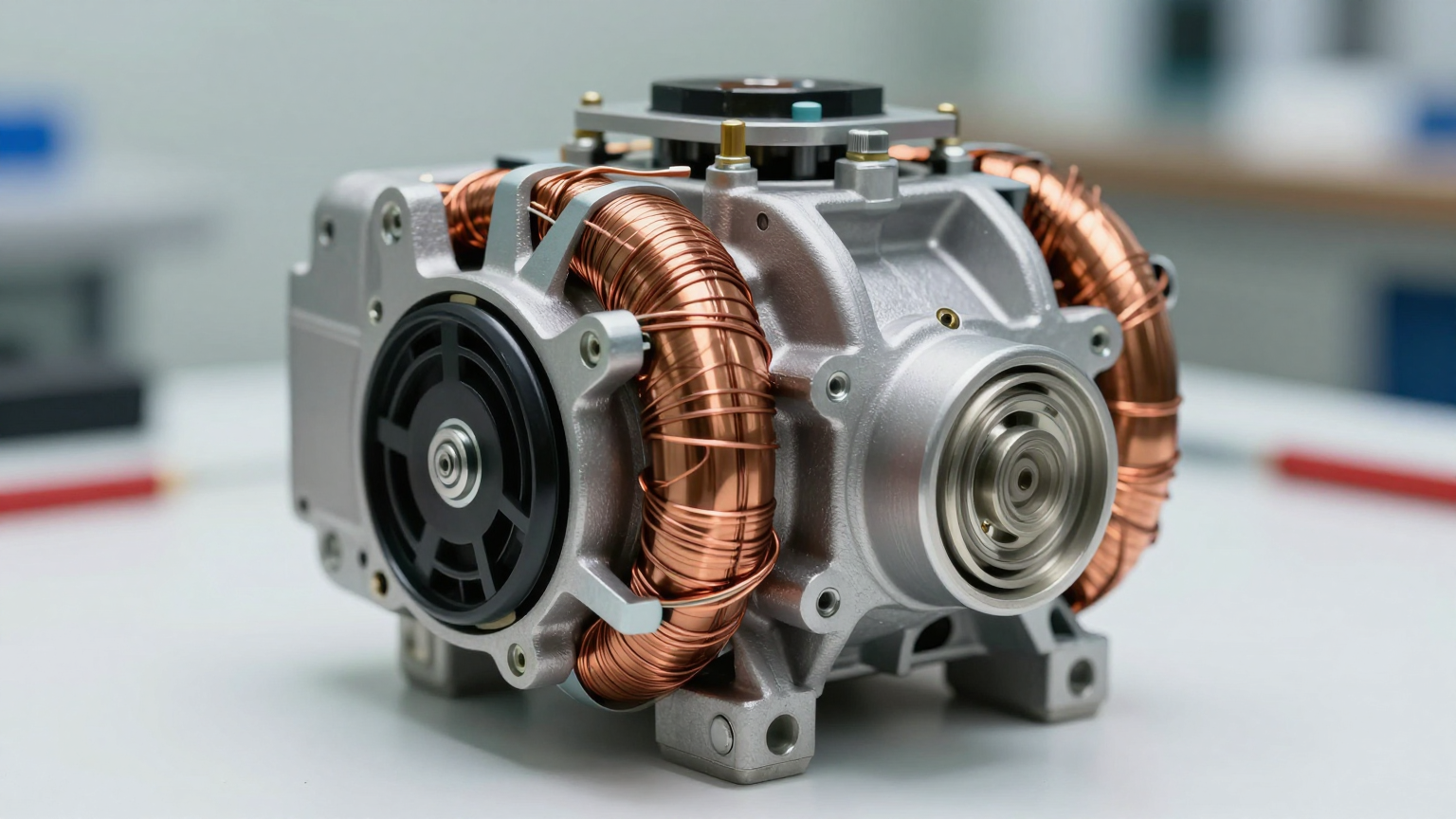

- Engineering Resolution: The cooling solution must have a sophisticated, integrated driver board that can handle voltage fluctuations and provide clean power to the compressor and fans. Furthermore, a system with a variable-speed compressor and blowers is highly advantageous. It can modulate its power draw to match the real-time heat load, reducing overall energy consumption and minimizing stress on the vehicle’s electrical system.

- Integration Trade-off: This requires more advanced power electronics within the cooling unit but delivers significant benefits in efficiency, acoustic noise, and reliability. It also enables features like soft-start to prevent large inrush currents, a critical consideration in mobile power systems and a key part of a holistic thermal management of rugged electronics plan.

Implementation and Verification Checklist

Proper installation is just as critical as proper selection. A perfectly specified unit can fail if it’s integrated poorly. Follow this checklist to ensure performance and reliability.

-

Mechanical Integration

- Mounting Surface: Ensure the enclosure wall is flat, rigid, and strong enough to support the cooling unit under expected shock and vibration loads.

- Vibration Dampening: Use rubber grommets or specialized vibration-dampening mounts, especially in high-vibration applications like construction or mining equipment.

- Sealing Gasket: Carefully install the supplied gasket between the cooling unit and the enclosure. Use a torque wrench to tighten fasteners to the specified values in a star pattern to ensure even compression and a perfect seal.

- Internal Airflow: Confirm that no cables, brackets, or other components obstruct the path of the cold air outlet or the warm air return. A clear, unimpeded circulation path is essential for effective thermal management of rugged electronics.

-

Electrical Integration

- Power Wiring: Use the recommended wire gauge for the current draw and the length of the wire run to prevent voltage drop.

- Circuit Protection: Connect the unit to a dedicated, fused circuit rated appropriately for the maximum current draw specified in the manual. This protects both the vehicle and the unit.

- Signal & Control: If using remote sensors or controls, route these wires separately from high-current power lines to prevent electromagnetic interference (EMI).

-

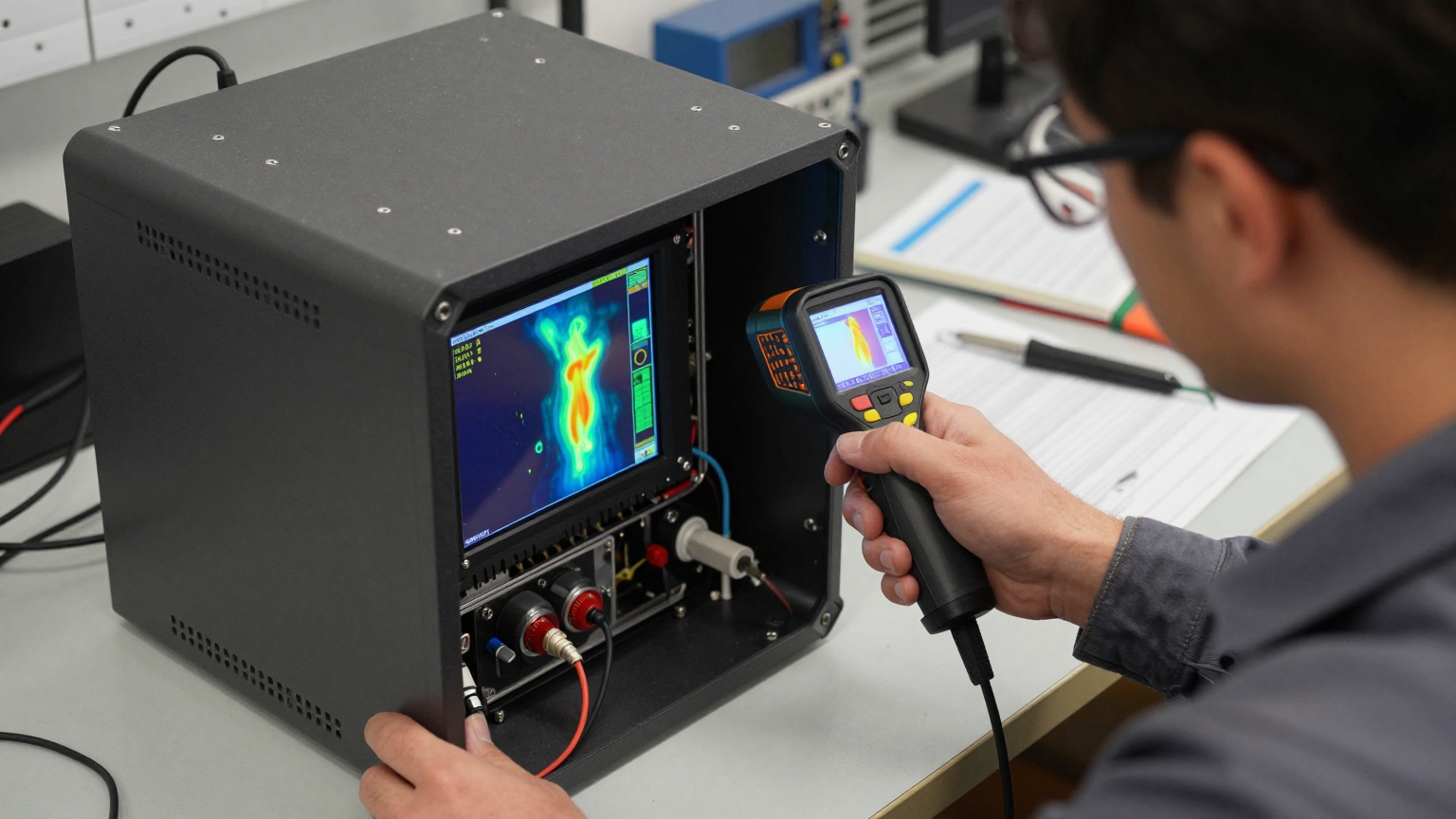

Thermal Validation

- Sensor Placement: Place thermocouples or temperature sensors directly on the most critical heat-generating components (e.g., CPU, FPGA, power amplifiers), not just in the general airflow.

- Worst-Case Testing: Perform a system-level acceptance test by running the electronics under full processing load within a thermal chamber set to the maximum expected ambient temperature. For mobile equipment, a real-world test on a hot, sunny day is invaluable.

- Data Logging: Log the internal temperatures over a full operational cycle to confirm that the thermal management of rugged electronics system maintains temperatures well within the components’ safe operating limits.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Here are answers to common questions and objections raised by engineers during the design phase of thermal management for rugged electronics.

1. Should I use a thermoelectric (Peltier) cooler or a DC air conditioner?

For heat loads below 50-100W and small temperature differentials, a thermoelectric cooler can be a simple solid-state solution. However, for higher heat loads, vapor-compression DC air conditioners are significantly more efficient (higher Coefficient of Performance), making them the superior choice for managing substantial heat in a constrained power environment.

2. What if my enclosure needs to be IP67 rated for temporary immersion?

An IP67 rating requires a cooling solution specifically designed for that level of sealing. The unit itself must have sealed connectors, a robust chassis, and a mounting system that guarantees the integrity of the enclosure penetration. This level of protection is a specialized requirement for the thermal management of rugged electronics.

3. How do you manage condensation inside the cabinet?

A properly sized DC air conditioner actively dehumidifies the trapped air inside the enclosure as it cools it. The moisture condenses on the cold evaporator coil and is managed by the unit’s integrated condensate removal system. This prevents condensation from forming on your electronics.

4. How much does direct sun exposure affect cooling performance?

Solar load is a major factor. A dark-colored enclosure sitting in direct sunlight can add hundreds of watts of external heat load. This must be calculated and added to the internal electronics’ heat load to correctly size the cooling unit. A reflective or shaded enclosure can significantly reduce this burden.

5. What is the single most important value I need to measure before selecting a cooler?

The total internal heat load, measured in watts. This is the sum of the power consumed by all components within the enclosure that is dissipated as heat. An inaccurate heat load calculation is the most common reason for specifying an undersized cooling unit.

6. How can I validate the cooling solution after installation?

The best method is empirical data logging. Use thermocouples to monitor the temperatures of critical components and the internal ambient air under worst-case operational (full CPU load) and environmental (hottest day) conditions. This data provides definitive proof that your thermal management of rugged electronics is successful.

7. Is truly dustproof electronics cooling possible with an air conditioner?

Yes, provided it is a closed-loop system. The entire purpose of this design is to seal the internal air circuit from the external environment. The internal air is continuously recirculated and cooled, while the external loop rejects the heat. There is no exchange of air, and therefore no ingress of dust.

Conclusion: Matching the Solution to the Environment

The strategy for effective thermal management of rugged electronics is not about choosing the most powerful cooler; it’s about creating a stable, predictable, and protected micro-environment where sensitive components can perform reliably. For electronics deployed in clean, temperature-controlled settings, a simple fan may be sufficient. But for off-road, mobile, or industrial applications where dust, moisture, and heat are constants, a sealed enclosure with active, closed-loop cooling is the only viable path to achieving the required levels of reliability and uptime.

This approach, centered on a miniature DC air conditioning system, directly addresses the primary failure modes—overheating and contamination—by creating a closed-loop environment that is impervious to external conditions. It is the definitive solution when performance cannot be compromised. If you are designing a system with these demanding constraints, our engineering team can help you accurately calculate your total thermal load and configure a solution. Contact us to discuss custom mounting options, challenging power budgets, and the specific environmental hazards of your thermal management of rugged electronics project.

0 条评论