Angle: This article addresses the critical decision moment of choosing between passive/filtered cooling and active, closed-loop air conditioning for sealed electronics enclosures. We focus on two primary failure modes: overheating from dust-clogged filters and short circuits from condensation. The dominant constraint is maintaining enclosure sealing integrity (IP/NEMA rating) against environmental hazards.

The Engineer’s Playbook for Thermal Management of Rugged Electronics

In the world of off-road vehicles, autonomous agriculture, and mobile industrial equipment, the premature failure of an electronic control unit is rarely a simple component issue. It’s an environmental one. When a high-value controller in a mining haul truck or a drone’s avionics package fails, the root cause is often traced back to a seemingly simple problem: heat, compounded by the relentless assault of dust, moisture, and vibration. The stakes are immense, leading to mission failure, expensive field service calls, and a tarnished reputation for reliability. The challenge of thermal management for rugged electronics is not just about removing watts; it’s about doing so while protecting the system from the world around it.

Many designs start with a fan and a filter, a solution that works perfectly well in a clean, climate-controlled room. But in the field, that approach can become the primary vector for failure. By the end of this technical playbook, you will have a clear engineering framework for deciding when to abandon open-loop cooling and invest in a robust, closed-loop system. In this article, we prioritize long-term system reliability in harsh environments over minimal upfront cost, exploring how active, closed-loop cooling solves the interconnected problems of heat, dust, and moisture, which is the cornerstone of effective dustproof electronics cooling.

Deployment Context: Where Simple Cooling Fails

Theoretical designs often diverge from field reality. Here are two common scenarios where conventional cooling methods prove inadequate for the demands of thermal management for rugged electronics.

Scenario A: Autonomous Agricultural Sprayer Drone

An agricultural drone carries a sealed avionics bay containing the flight controller, GPS, and sensor fusion hardware. A previous design iteration used a high-static-pressure fan with a fine mesh filter for cooling. Within weeks of deployment, fine pollen and aerosolized chemical deposits completely clogged the filter. The resulting thermal throttling of the processor led to unstable flight behavior and GPS signal degradation. The core constraint was the impossibility of daily filter maintenance on a fleet of drones operating in remote fields, demanding a zero-maintenance, sealed cooling solution.

Scenario B: Control Cabinet on a Mining Haul Truck

The autonomous navigation and sensor control cabinet is mounted directly to the chassis of a large mining haul truck. This location subjects the electronics to constant, high-amplitude vibration and shock. The environment is saturated with abrasive rock dust and the entire vehicle is subjected to high-pressure water jets during cleaning. The original fan-cooled system failed catastrophically when fine, slightly conductive metallic dust was pulled into the enclosure, coating the PCBs and causing multiple short circuits. The operational constraint is zero unplanned downtime, making the integrity of the sealed enclosure paramount.

Common Failure Modes and System Constraints

When designing for harsh mobile environments, engineers must anticipate a different class of failures. The problems are often cascading, where one environmental factor exacerbates another. Here are the most common failure modes, ranked by impact and likelihood.

- Gradual Performance Drop → Cause: Clogged air filters or heat sink fins → Why it matters: Leads to CPU/GPU throttling, slower data processing, and mission-critical errors.

- Sudden Component Failure → Cause: Condensation on PCBs → Why it matters: Occurs when humid ambient air is drawn into a cooling enclosure, hitting its dew point and causing catastrophic short circuits.

- Intermittent Faults → Cause: Vibration and shock damage → Why it matters: Causes solder joint fatigue and connector fretting; standard fan motor bearings are often the first components to fail, halting all airflow.

- Catastrophic Short Circuit → Cause: Conductive dust ingress → Why it matters: Fine dust bypasses insulation and creates unintended electrical paths, a critical risk in mining, construction, and manufacturing.

- Power System Overload → Cause: Inefficient or struggling cooling system → Why it matters: As fans work harder to pull air through clogged filters, their current draw increases, straining the vehicle’s limited DC power budget.

- Accelerated Corrosion → Cause: Salt fog or chemical vapor ingress → Why it matters: Compromises PCB traces and connector integrity in marine, coastal, or agricultural applications, leading to hard-to-diagnose faults.

- Premature Maintenance Cycles → Cause: Reliance on filter changes → Why it matters: Increases total cost of ownership and introduces risk of improper sealing during service.

Engineering Fundamentals: The Closed-Loop Imperative

The core principle that resolves the majority of the failure modes above is the transition from an open-loop to a closed-loop cooling system. This is the foundation of proper thermal management for rugged electronics.

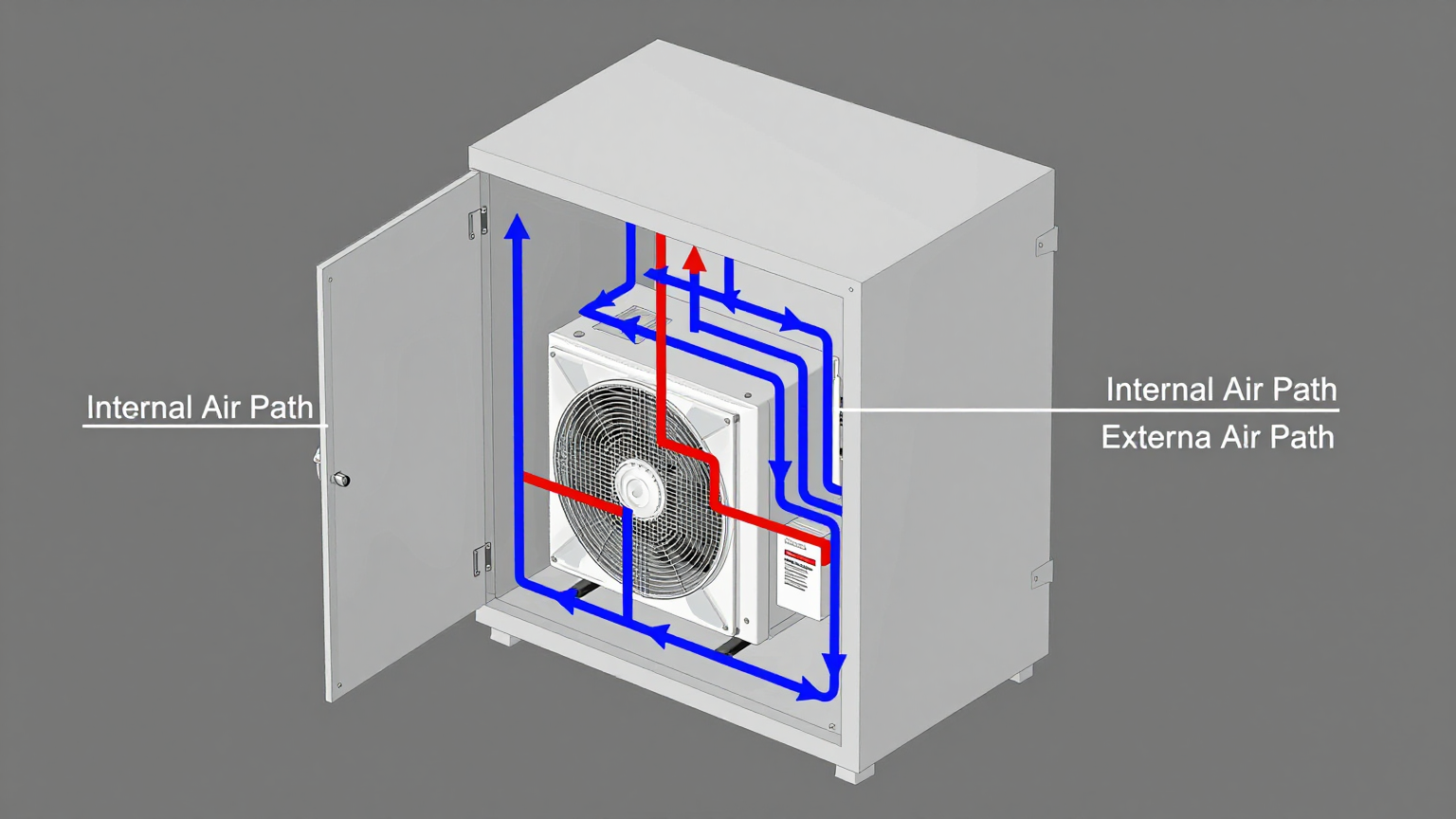

In a closed-loop system, the air inside the electronics cabinet is completely isolated from the ambient outside air. The heat path works like this:

- Internal components like processors and power supplies generate heat, raising the temperature of the trapped air inside the enclosure.

- This hot internal air is circulated by a fan across the cold evaporator coil of a compact DC air conditioner.

- Heat from the air is absorbed by the refrigerant inside the evaporator, causing the refrigerant to turn from a liquid to a gas.

- The cool, dehumidified air is then directed back over the electronics.

- The refrigerant gas, now carrying the heat, is pumped by a compressor to the external condenser coil.

- An external fan blows ambient air over the condenser, transferring the heat from the refrigerant to the outside world. The refrigerant cools and returns to a liquid, ready to repeat the cycle.

The critical takeaway is that the two air streams—internal and external—never mix. This maintains the enclosure’s seal against dust, water, and chemicals.

Common Misconception: “My enclosure is overheating. I just need a more powerful fan.”

Engineering Correction: A more powerful fan often makes the problem worse in a contaminated environment. It accelerates the rate at which filters clog and pulls in more humid or dusty air, increasing the risk of condensation and short circuits. The fundamental problem isn’t a lack of airflow; it’s the failure to maintain a clean, sealed internal environment. True dustproof electronics cooling requires isolation, not just ventilation.

Specification Gateway: Sizing the Solution

Once the need for a closed-loop system is established, the selection process becomes data-driven. The first step is to match the cooling capacity and voltage to the application’s requirements. While every project is unique, a baseline understanding of available technology is crucial. The Rigid Chill Micro DC Aircon series, for example, provides a range of compact, direct-current solutions designed for these environments.

How to read these specifications for your decision: The Nominal Cooling Capacity is your starting point, representing performance under standard test conditions. This value must be adjusted (derated) for your maximum expected ambient temperature and solar load. The DC Voltage must align with the vehicle or system’s power bus (e.g., 12V, 24V, or 48V). The choice of refrigerant often depends on regional environmental regulations and specific performance characteristics.

| Model (Example) | DC Voltage | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC (Pro) | 12V | 450W | R134a |

| DV1920E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 450W | R134a |

| DV1930E-AC (Pro) | 48V | 450W | R134a |

| DV3220E-AC (Pro) | 24V | 550W | R134a |

Engineering Selection Matrix: Three Logic Gates

An effective selection process for the thermal management of rugged electronics moves through a series of non-negotiable logic gates. If your application fails any of these tests, a simple fan-and-filter solution is likely to result in field failure.

Gate 1: Sealing Requirement vs. Contaminant Load

- The Constraint Gate: Does the system require an IP6X, NEMA 4, or NEMA 12 rating? Is the operational environment characterized by high levels of dust, moisture, salt spray, or chemical vapors?

- The Decision Trigger: If the answer is yes, any cooling solution that relies on exchanging air with the outside environment is fundamentally non-compliant and presents an unacceptable risk.

- Engineering Resolution: This immediately mandates a closed-loop cooling architecture. The design focus shifts from filtering ambient air to removing heat from a completely sealed volume. This is the first and most important step toward genuine dustproof electronics cooling.

- Integration Trade-off: This path requires a higher initial investment in a sealed-system cooler but virtually eliminates the cost and reliability risks associated with filter maintenance and contaminant ingress.

Gate 2: Thermal Delta vs. Ambient Ceiling

- The Constraint Gate: What is the maximum allowable internal temperature for your most sensitive component, and what is the absolute maximum external ambient temperature the system will experience?

- The Decision Trigger: If the required internal temperature is lower than the maximum external ambient temperature (e.g., electronics must be kept at 35°C when the outside air is 50°C), then a passive solution like a heat exchanger cannot work.

- Engineering Resolution: The laws of thermodynamics dictate that an active, refrigerant-based vapor-compression system is required. Only a system like a Micro DC Aircon can create a temperature differential where the inside is cooler than the outside.

- Integration Trade-off: An active system adds a compressor and increases power consumption compared to a heat exchanger, but it is the only technology capable of guaranteeing performance in high-heat environments.

Gate 3: Power Budget vs. Cooling Density

- The Constraint Gate: What is the total heat load (in watts) generated by the internal electronics? How much power (in amps) is available on the specified DC bus (12V/24V/48V)?

- The Decision Trigger: When the internal heat load surpasses what can be safely dissipated through the cabinet’s natural surface area, and the power budget can support an active cooling device (typically 100-500W).

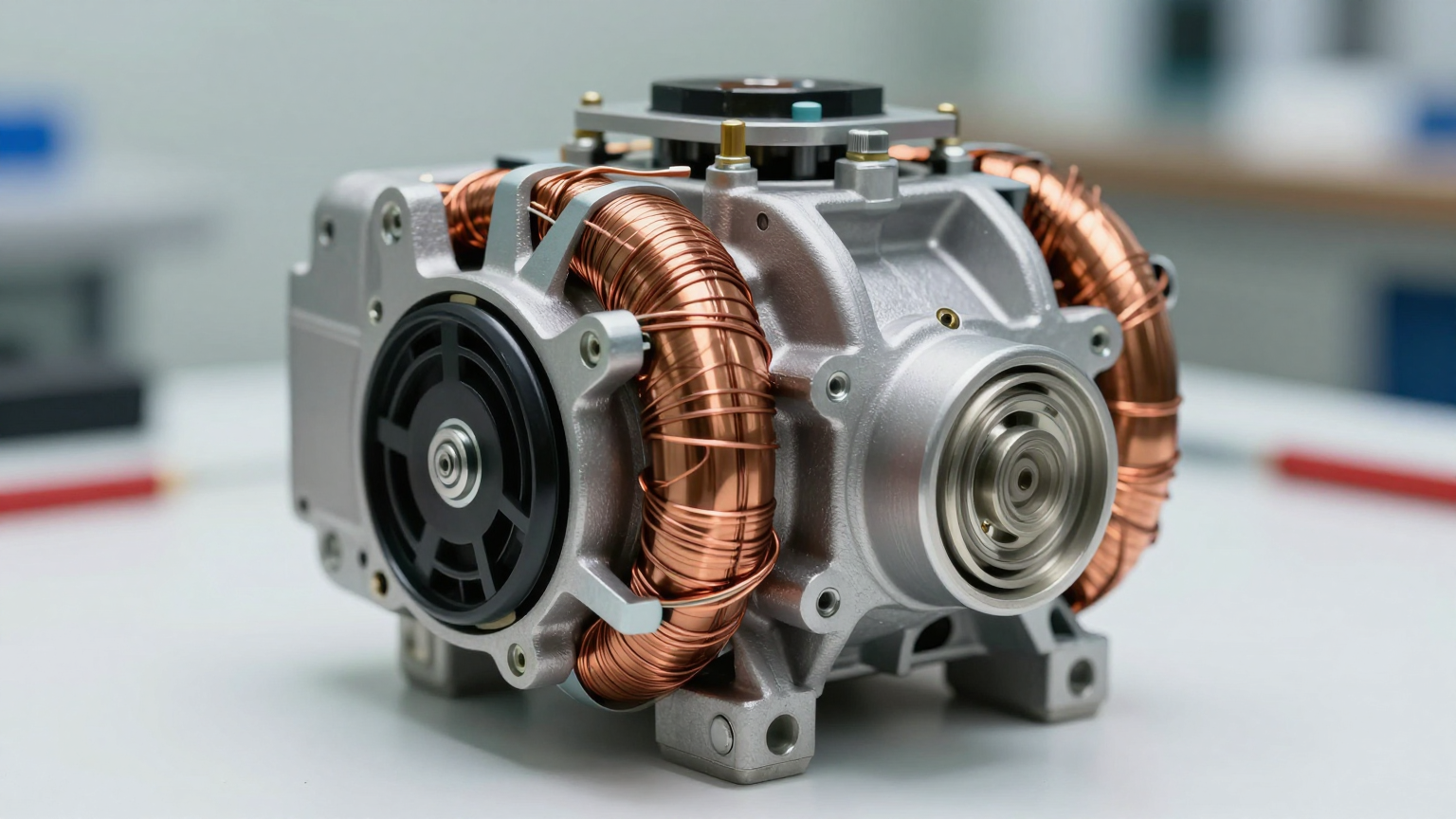

- Engineering Resolution: Select a variable-speed DC air conditioner that can modulate its capacity to match the heat load. An inverter-driven compressor can run at a low speed during idle periods to save power and ramp up to full capacity under heavy processing loads, providing an efficient and responsive approach to the thermal management of rugged electronics.

- Integration Trade-off: Requires more sophisticated power wiring and potentially a dedicated circuit, but offers superior efficiency and prevents the energy waste associated with oversized, fixed-speed on/off systems.

Implementation and Verification Checklist

Proper installation is as critical as proper selection. A poorly integrated unit will fail to protect your electronics. Follow this checklist to ensure reliability.

- Mechanical Integration

- Mounting: Use the recommended mounting hardware, including vibration-dampening grommets or isolators, especially in high-shock mobile applications.

- Sealing Surface: Ensure the enclosure surface is flat and clean. Apply the sealing gasket evenly and torque the fasteners to the specified value to create a continuous, watertight seal.

- Airflow Integrity: Verify that there are no obstructions within the cabinet blocking the inlet or outlet of the cold air stream. Likewise, ensure the external condenser fans have unrestricted airflow.

- Electrical Integration

- Power Wires: Use the wire gauge specified in the manual to prevent voltage drop, especially over long wire runs.

- Circuit Protection: Install an appropriately rated fuse or circuit breaker on the positive line as close to the power source as possible.

- Control Signals: If using a remote thermostat or controller, ensure wiring is shielded and routed away from high-noise power cables.

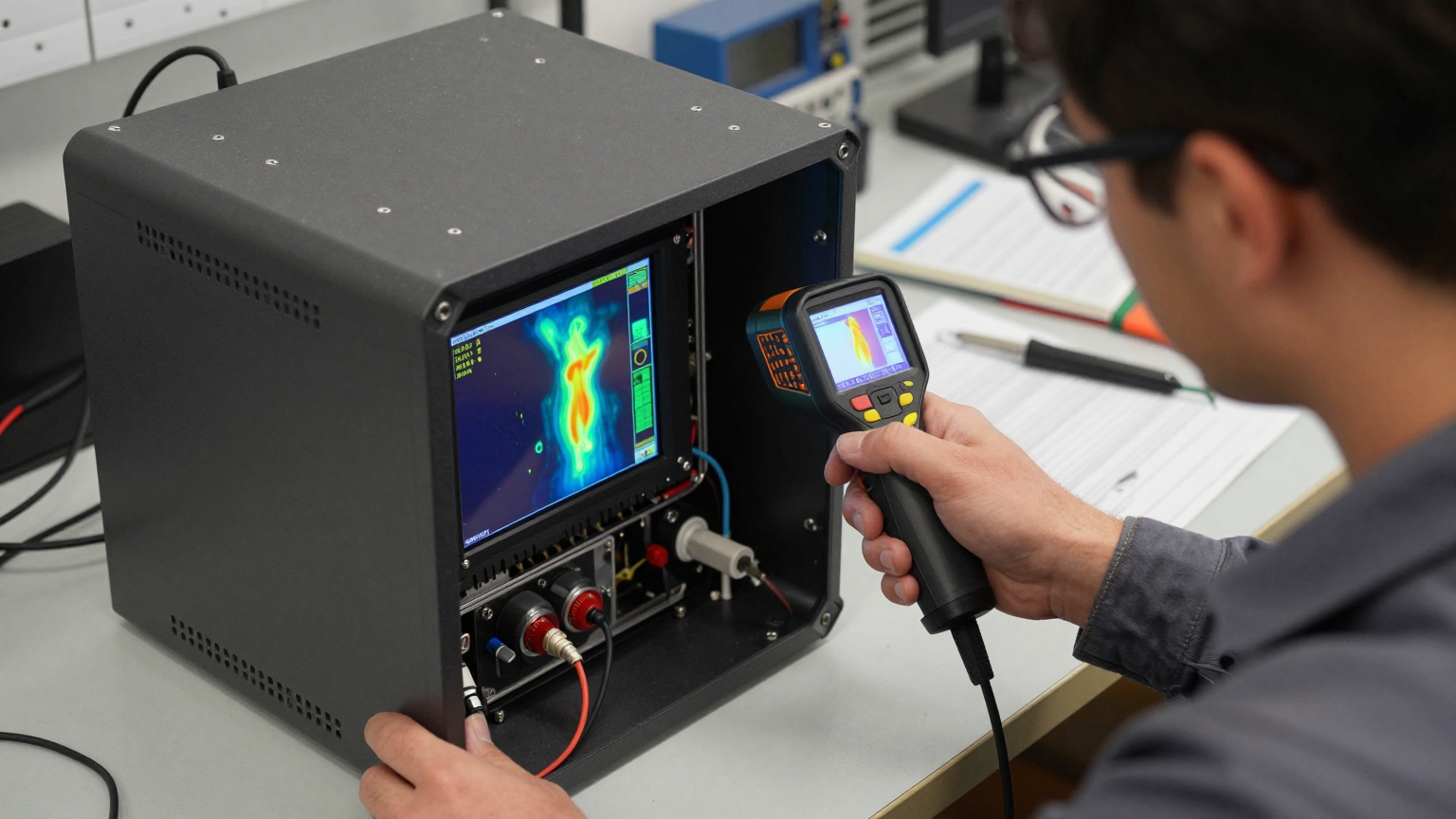

- Thermal Validation

- Sensor Placement: Place validation thermocouples near the most heat-sensitive components and in the general cabinet air, but not directly in the path of the cold air outlet, to get an accurate reading of system performance.

- Acceptance Testing: The most critical step. Operate the electronics under full load in a thermal chamber or on the hottest operational day to verify that the internal temperature remains stable and below the maximum allowable limit. This validates your entire strategy for the thermal management of rugged electronics.

- Maintenance Plan

- External Coil Cleaning: Schedule periodic cleaning of the external condenser coils with compressed air to remove accumulated dust or debris, which can impede heat transfer.

- Gasket Inspection: Annually inspect the integrity of the mounting gasket, especially on equipment that experiences high vibration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Should I use a thermoelectric cooler (TEC) or a compressor-based DC air conditioner?

TECs (Peltier devices) are simple and reliable for very low heat loads (typically under 100W) and small temperature differentials. For higher heat loads and better energy efficiency, a compressor-based vapor-compression system is far superior.

How does a closed-loop cooler affect my enclosure’s IP or NEMA rating?

When installed correctly with the proper gasket, a closed-loop air conditioner is designed to maintain or even enhance the enclosure’s original IP/NEMA rating, as it seals the cutout it occupies.

What about condensation management inside the cabinet?

Because a closed-loop system traps a fixed volume of air, the air conditioner quickly removes the initial humidity. Any condensate collected on the cold evaporator coil is typically channeled to an external evaporation system, so no liquid water remains in the enclosure.

How do these units handle direct sun exposure (solar load)?

Solar load is a significant heat source and must be calculated and added to the internal electronic heat load. A light-colored or shielded enclosure can help, but the cooling unit must be sized to handle the combined load on the hottest, sunniest day.

What is the first thing I must measure before selecting a cooling unit?

You need two key numbers: the total internal heat load generated by all components in watts, and the maximum expected ambient temperature combined with any solar load effects. Without these, any selection is a guess.

How do I validate the thermal management of rugged electronics after installation?

The best validation is empirical testing. Run the system at its highest electrical load in the hottest real-world conditions (or a thermal chamber simulating them). Monitor the internal cabinet temperature at critical locations to ensure it stays well below the specified maximum for all components.

Can these compact DC units handle the shock and vibration of an off-road vehicle?

Units designed for mobile applications use robust components like brushless DC (BLDC) inverter compressors and reinforced frames to withstand significant shock and vibration. Always verify that the unit’s tested vibration profile matches your application’s requirements.

Conclusion: Matching the Tool to the Environment

The decision to move beyond simple fans is a critical inflection point in the design of reliable, hardened systems. While fans and filters are adequate for benign, stationary environments, they represent a significant liability in mobile and industrial applications where dust, moisture, and heat conspire against electronics. A successful strategy for the thermal management of rugged electronics is built on a closed-loop philosophy, isolating sensitive components from the hostile outside world.

The best-fit solution is an active, DC-powered air conditioning system when one or more of these conditions are true: the enclosure must be sealed (IP/NEMA rated), the internal temperature must be kept below the external ambient temperature, or the internal heat load is too high for passive dissipation. This approach trades a higher initial component cost for a dramatic increase in system reliability, uptime, and service life.

If you are designing a system that faces these challenges, our engineering team can help you calculate your total thermal load and select a cooling solution optimized for your specific enclosure geometry, power constraints, and environmental hazards. Contact us to discuss your project and ensure your electronics are protected.

0 条评论