The Forensic Path: When Passive Venting Becomes a Liability

It usually starts with a “ghost” failure. A remote telemetry unit in the Permian Basin goes offline intermittently between 2:00 PM and 4:00 PM. A digital signage kiosk in a Las Vegas outdoor mall experiences screen blackouts (isotropic failure) during peak summer months. The logs show no software errors, and the power supply tests fine in the lab. The culprit is almost always thermal saturation—a specific failure mode where the enclosure’s ability to shed heat passively is outpaced by the solar load and internal dissipation.

For OEM engineers and system integrators, the design phase often involves a critical decision point: sealed outdoor enclosure cooling tradeoffs; active cooling justified by component longevity, or passive cooling justified by lower BOM costs? While passive methods like filtered fans or heat sinks are attractive for their simplicity, they rely entirely on a temperature differential ($\Delta T$) that may not exist in harsh outdoor environments. When the ambient air temperature approaches or exceeds the maximum operating temperature of the internal electronics, passive cooling physically cannot remove heat. The result is an “oven effect” inside the NEMA 4X or IP65 enclosure.

This article analyzes the engineering logic behind these thermal decisions. We will dissect the failure mechanisms of passive systems in high-ambient conditions and define the precise operational thresholds where active cooling—specifically Micro DC Aircon technology—becomes not just an option, but a requirement for system survival.

Deployment Context: The Hostility of the Edge

To understand the necessity of active cooling, we must first quantify the environment. We are not discussing climate-controlled server rooms. We are analyzing deployment scenarios where the environment is an active aggressor.

Scenario A: The Desert Telecom Node

Consider a 5G small cell repeater station in Phoenix, Arizona. The ambient air temperature can reach 48°C (118°F). However, the “effective” temperature is much higher. Direct solar loading adds significant thermal energy to the enclosure surface. If the enclosure is painted dark grey or black for aesthetic reasons, the surface temperature can easily exceed 75°C. Inside, the FPGA-driven telecommunications equipment has a thermal shutdown limit of 85°C. The $\Delta T$ available for passive heat transfer is virtually non-existent. In fact, heat may flow into the enclosure from the chassis walls.

Scenario B: The Coastal Sensor Rig

In a maritime monitoring station off the coast of Florida, the challenge shifts from pure heat to humidity and corrosion. The ambient temperature might be a manageable 35°C, but the relative humidity is 95%, and the air is laden with salt spray. Using a filtered fan (passive cooling) pulls this corrosive air directly over the PCBs. Salt bridges form, leading to short circuits and premature board failure. Here, the enclosure must be sealed (NEMA 4X / IP65). Once sealed, the heat generated by the power supply and processor is trapped. The sealed outdoor enclosure cooling tradeoffs; active cooling justified logic here is driven by the need for isolation as much as thermal management.

Technical Friction Points & Failure Modes

When relying on passive cooling or undersized active solutions in these environments, several specific failure modes emerge. These are the “unseen enemies” that degrade uptime and increase Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

- Thermal Runaway (The $\Delta T$ Collapse): Passive cooling (convection/conduction) is linear. It depends on the inside being hotter than the outside. When ambient temperature rises to match the internal temperature, cooling stops. If ambient exceeds internal targets, the enclosure heats up.

- Isotropic Phase Change (Displays): For outdoor kiosks, LCD panels have a clearing point (often around 100°C, but surface temps rise fast). Without active chilling to counteract solar gain, the liquid crystals lose their orientation, and the screen turns black.

- Derating & Throttling: Modern CPUs and GPUs protect themselves by throttling performance when they hit thermal junctions (often 90°C-100°C). Your high-speed industrial PC effectively becomes a low-speed legacy device during the hottest part of the day, causing data latency.

- Contaminant Ingress: “Breathable” enclosures (IP54 or lower) allow dust and moisture ingress. In mining or agricultural applications, conductive dust can bridge component pins, causing catastrophic shorts.

Engineering Fundamentals: The Logic of Closed-Loop Cooling

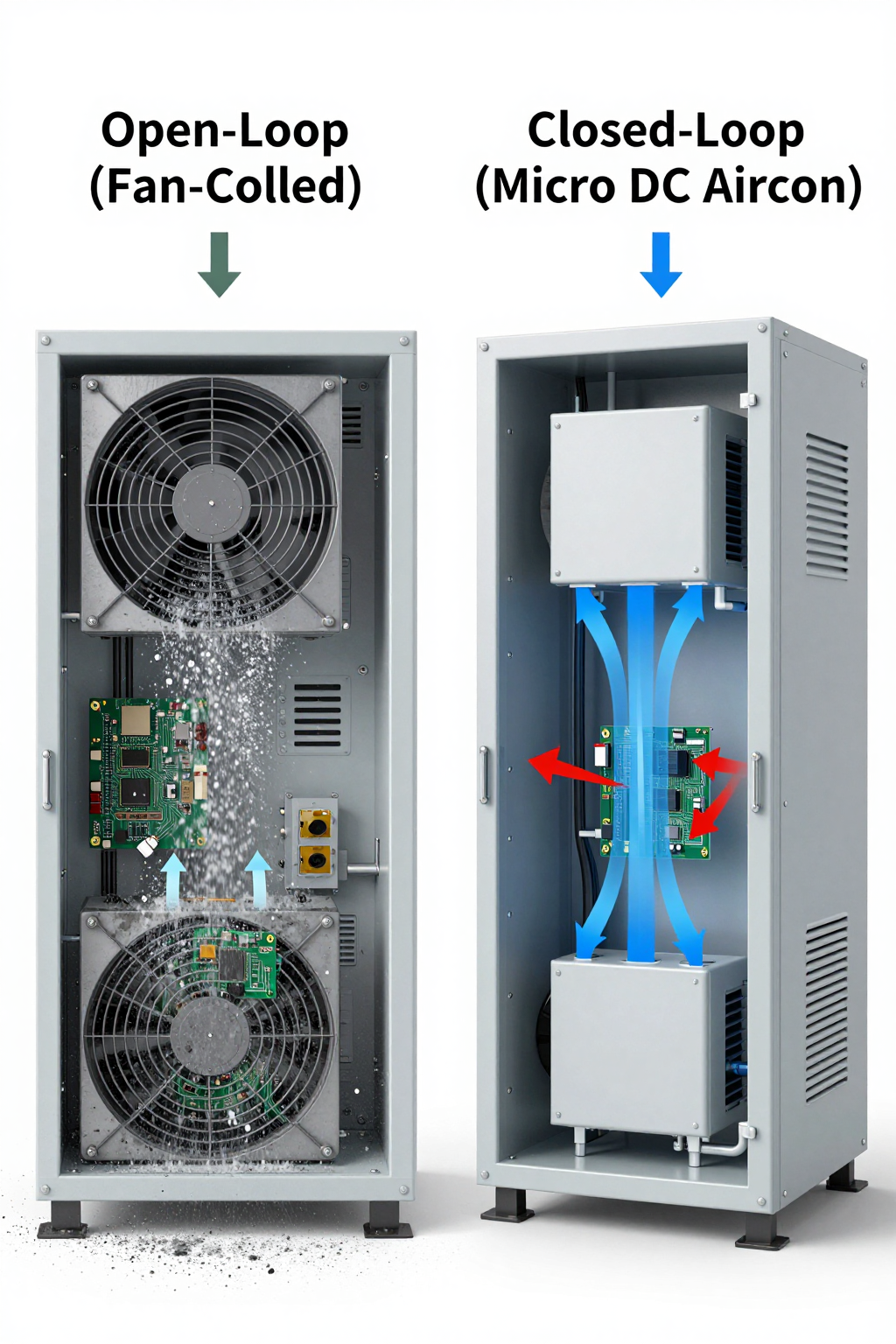

The fundamental difference between fan-based cooling and active refrigeration is the air path. Understanding this distinction is key to navigating sealed outdoor enclosure cooling tradeoffs; active cooling justified by the physics of isolation.

Open-Loop vs. Closed-Loop

Open-Loop (Fans): Uses ambient air to cool components. The air inside the enclosure is constantly replaced. This equalizes the internal temperature with the ambient temperature (at best) plus a rise due to inefficiency. It brings the outside environment inside.

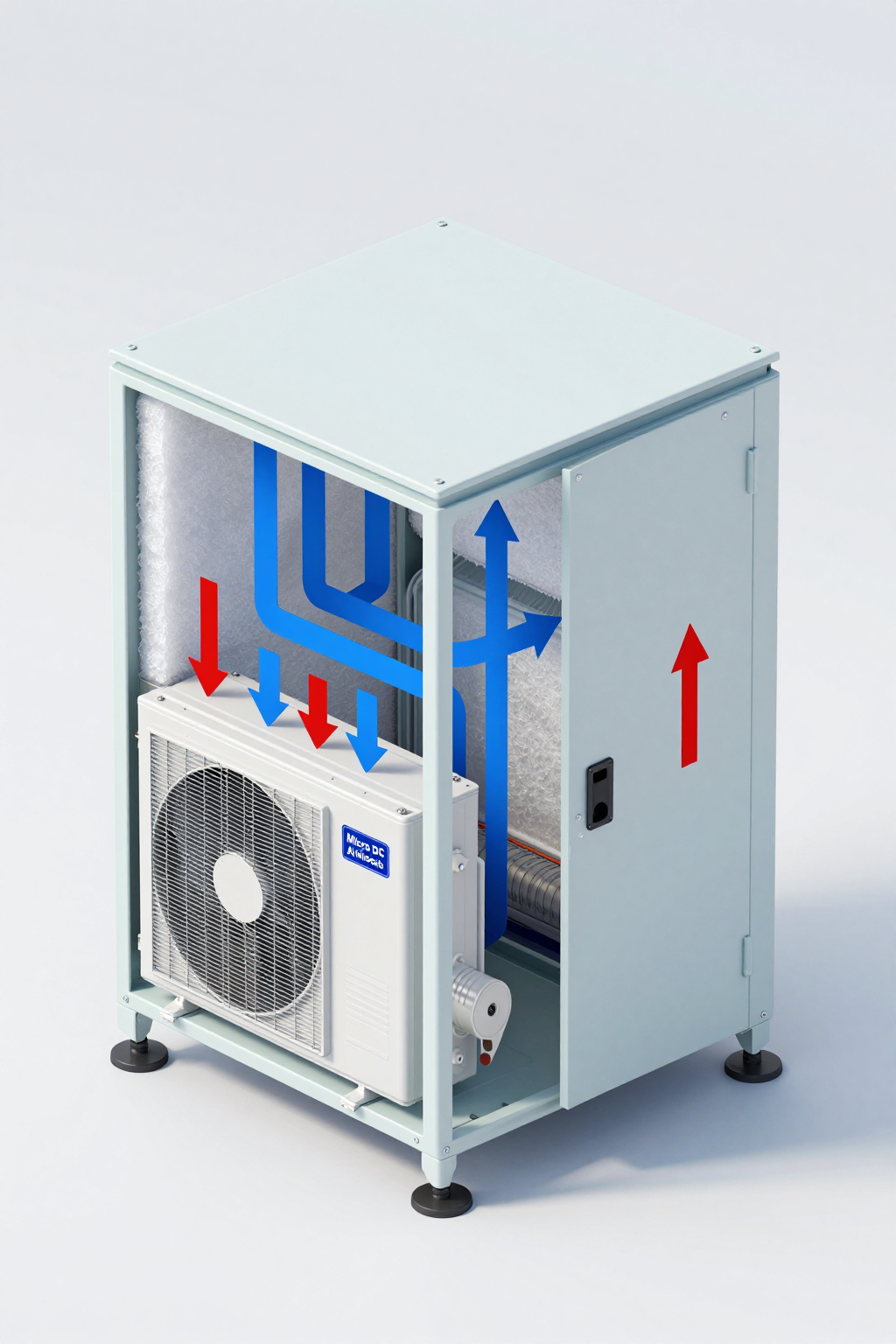

Closed-Loop (Micro DC Aircon): The air inside the enclosure never leaves. It is recirculated through an evaporator coil, cooled, and blown back over the components. The heat is transferred to a refrigerant, pumped to a condenser, and rejected to the outside air. This physically isolates the electronics from the environment.

Vapor Compression Thermodynamics

Active cooling uses a vapor-compression cycle (Compressor, Condenser, Expansion Valve, Evaporator). This allows the system to pump heat “uphill”—moving thermal energy from a cooler interior to a hotter exterior. This is impossible with fans or heat pipes alone. By using a refrigerant like R134a, the system absorbs heat by boiling the refrigerant at a low pressure (inside) and rejects it by condensing the refrigerant at high pressure (outside).

For mobile and off-grid applications, the efficiency of this cycle is critical. This is where the Micro DC Aircon series excels. Unlike AC-powered units that require heavy inverters (creating more heat and loss), DC-native compressors run directly off the battery bank (12V, 24V, or 48V), eliminating conversion losses.

Performance Data & Verified Specs

When evaluating active cooling solutions, specific technical parameters dictate success. The Arctic-tek Micro DC Aircon series is designed for high power density in compact footprints. Below are the verified specifications for the DV series, which utilize miniature BLDC inverter rotary compressors.

| Model (Pro Series) | Voltage (DC) | Nominal Cooling Capacity | Refrigerant | Compressor Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV1910E-AC | 12V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1920E-AC | 24V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV1930E-AC | 48V | 450W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

| DV3220E-AC | 24V | 550W | R134a | BLDC Inverter Rotary |

Key Engineering Notes:

- Capacity vs. Size: Providing 450W–550W of cooling in a miniature footprint allows these units to fit into tight kiosk headers or telecom cabinets where traditional AC units would be too bulky.

- Voltage Flexibility: The availability of 12V, 24V, and 48V options aligns with standard telecom and automotive power buses, simplifying integration.

- Inverter Control: The BLDC inverter compressor allows for variable speed operation. This means the unit can ramp down when the heat load is low, conserving battery life in off-grid solar applications.

For applications requiring extreme temperature control, such as medical transport, the Micro DC Aircon provides the necessary thermal stability that passive solutions cannot achieve.

Field Implementation Checklist

Deploying active cooling requires a holistic approach to enclosure design. It is not as simple as cutting a hole and bolting on a unit. Follow this checklist to ensure the sealed outdoor enclosure cooling tradeoffs; active cooling justified decision yields maximum ROI.

1. Mechanical Integration

- Sealing Integrity: Ensure the enclosure is truly NEMA 4X / IP65 compliant before installing the cooler. Use high-quality gaskets (EPDM or Neoprene) at the mounting interface.

- Airflow Management: Avoid “short-cycling.” Ensure the cold air discharge from the aircon is not immediately sucked back into the return intake. Use baffles or ducting to direct cold air to the hottest components (e.g., the CPU or power supply).

- Mounting Orientation: While some miniature compressors are robust, verify the allowable tilt angles if the equipment is mobile. Generally, upright operation is preferred for proper oil lubrication.

2. Electrical & Power

- Cable Sizing: DC compressors draw significant current, especially at 12V. Undersized cables cause voltage drop, which can trigger the driver board’s low-voltage cutoff protection. Use appropriate gauge wiring based on the run length and max current draw.

- Overcurrent Protection: Always install a fuse or breaker on the supply line matched to the unit’s startup and max current specifications.

3. Thermal Logic

- Insulation: Active cooling works best in an insulated environment. Lining the enclosure with closed-cell foam insulation reduces the solar heat load significantly, allowing the aircon to focus on the internal heat generation.

- Set Point Strategy: Do not set the target temperature lower than necessary. If 35°C is safe for the electronics, setting the thermostat to 20°C wastes energy and increases the risk of condensation on the outside of the enclosure.

Expert Field FAQ

Q: Can I use a Micro DC Aircon on a battery-only solar system?

A: Yes. The DV series (e.g., DV1920E-AC) is designed for DC efficiency. However, you must calculate your battery bank size based on the duty cycle. If the unit runs 50% of the time at 450W cooling, your battery capacity must support that load through the night or cloudy periods.

Q: What happens if the ambient temperature exceeds the rated range?

A: Vapor compression systems have limits. If the condenser gets too hot (e.g., >55°C ambient), the high-side pressure may trip the safety switch. For extreme climates, ensure the condenser has access to the coolest possible air (shade) and is not recirculating its own hot exhaust.

Q: How do I handle condensation inside the enclosure?

A: Cooling air removes moisture. The Micro DC Aircon will act as a dehumidifier. You must route the condensate drain tube out of the enclosure through a sealed port. Ensure the tube is not kinked and has a downward slope.

Q: Is R134a the only refrigerant option?

A: While R134a is standard for many models like the DV1910E-AC, the platform supports other refrigerants like R290 and R1234yf depending on the specific model configuration and regional environmental regulations.

Q: Why not just use a Peltier (Thermoelectric) cooler?

A: Peltier coolers are solid-state but notoriously inefficient (COP often < 0.6). For loads above 100W, they consume excessive power compared to a vapor-compression system (COP > 2.0-3.0). For a 450W load, a Peltier would require massive power input, making it impractical for most mobile or solar applications.

Q: Does the orientation of the compressor matter?

A: Yes. Rotary compressors rely on oil for lubrication. While miniature DC compressors are designed for mobile vibration resistance, they generally need to operate within specific tilt angles (often < 30 degrees) to prevent oil starvation.

Conclusion & System Logic

The decision to move from passive to active cooling is rarely taken lightly due to the perceived increase in complexity and cost. However, when analyzing the sealed outdoor enclosure cooling tradeoffs; active cooling justified by the cost of downtime, the math changes. A single failure of a critical telemetry node or a digital billboard in direct sunlight can cost more in repairs and lost revenue than the upfront investment in a robust thermal management system.

By integrating a Micro DC Aircon, engineers effectively decouple the internal operating environment from the external chaos. Whether you are dealing with the scorching heat of a desert deployment or the corrosive salt fog of a coastal rig, active cooling ensures that your electronics operate within their design specifications, regardless of what the weather dictates.

For engineers designing the next generation of outdoor automation, the path forward involves recognizing that heat is a contaminant as damaging as dust or water. Treating it with the same level of rigorous exclusion—via closed-loop active cooling—is the hallmark of a resilient system.

0 条评论